Who are Yemen’s Houthis?

Shiite Houthi followers rally to mark the day of Ashura and the 4th anniversary of their takeover of the Yemeni capital, in Sanaa, Yemen, Sept. 20, 2018.

Fully half of Yemen’s population — 14 million people — are on the brink of starvation. Some analysts blame their inability to access basic foodstuff on escalating conflict between two religious factions: the country’s Sunni Muslims and its Houthis. The Houthis belong to the Shiite branch of Islam.

Saudi Arabia, which shares a border with Yemen and is predominantly Sunni, has been helping Yemen’s government forces try to regain control over Houthi-held parts of the country. For several weeks, a Saudi-led coalition has unleashed near-continuous airstrikes on Houthi strongholds including access points for the majority of humanitarian aid coming into the country.

What are the Houthis’ religious beliefs?

Roots of Houthi movement

Just as the Protestant tradition is subdivided into Methodists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and others, Shiite Islam is also subdivided. Houthis belong to the Zaydi branch.

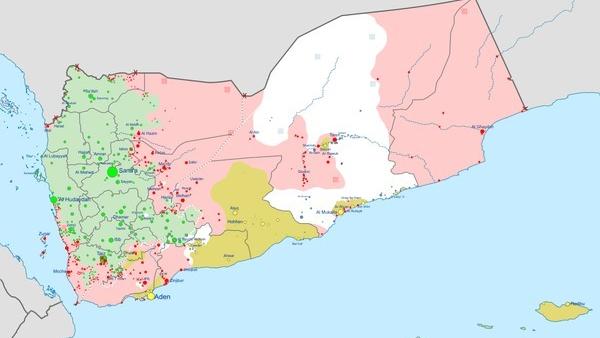

From the ninth century onward — for a thousand years — a state ruled by Zaydi religious leaders and politicians existed in northern Yemen. Then, in 1962, Egyptian-trained Yemeni military officers toppled the Zaydi monarchy and replaced it with a republic. Because of their ties to the ancient regime, Zaydis were perceived as a threat to the new government and were subjected to severe repression.

Nearly three decades later, in 1990, the region known as South Yemen merged with North Yemen to become the Republic of Yemen. Zaydis remained a majority in the north and west of the country, and also in the capital city of Sanaa. However, in terms of the overall population, they became a minority.

According to a 2010 CIA estimate, 65 percent of Yemen’s people are Sunnis and 35 percent are Shiites. The majority of those Shiites are Zaydis. Jews, Bahais, Hindus and Christians make up less than 1 percent of inhabitants, many of whom are refugees or temporary foreign residents.

To reduce the dominance of Zaydis in the north, government authorities encouraged Muslims belonging to two Sunni branches with links to Saudi Arabia — Salafis and Wahhabis — to settle in the heart of the Zaydis’ traditional territories.

Start of Houthi insurgency

Contributing to this trend, in the early 1990s, a Yemeni cleric founded a teaching institute in the Zaydis’ heartland. This cleric, educated in Saudi Arabia, developed a version of Salafi Islam.

His institute proselytized with the goal of reforming Muslims through conversion. It educated thousands of Yemeni students and, in less than three decades, the new religious group grew large enough to compete with older groups such as the Zaydis.

According to scholar Charles Schmitz, the Houthi insurgency began in the early 1990s, spurred, in part, by Zaydi resistance to growing Salafi and Wahhabi influence in the north.

Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, son of a prominent Zaydi cleric, gave the grassroots movement its name. He coalesced support among his followers around a narrative of Houthis as defenders and revivers of Zaydi religion and culture.

Related: The rise of the Houthis: A brief history of Yemen’s new power brokers

Sunni vs. Zaydi Shiite beliefs

What beliefs set Zaydis apart from Sunni Muslims? That is an old story, dating back to the seventh century when the Prophet Muhammad died.

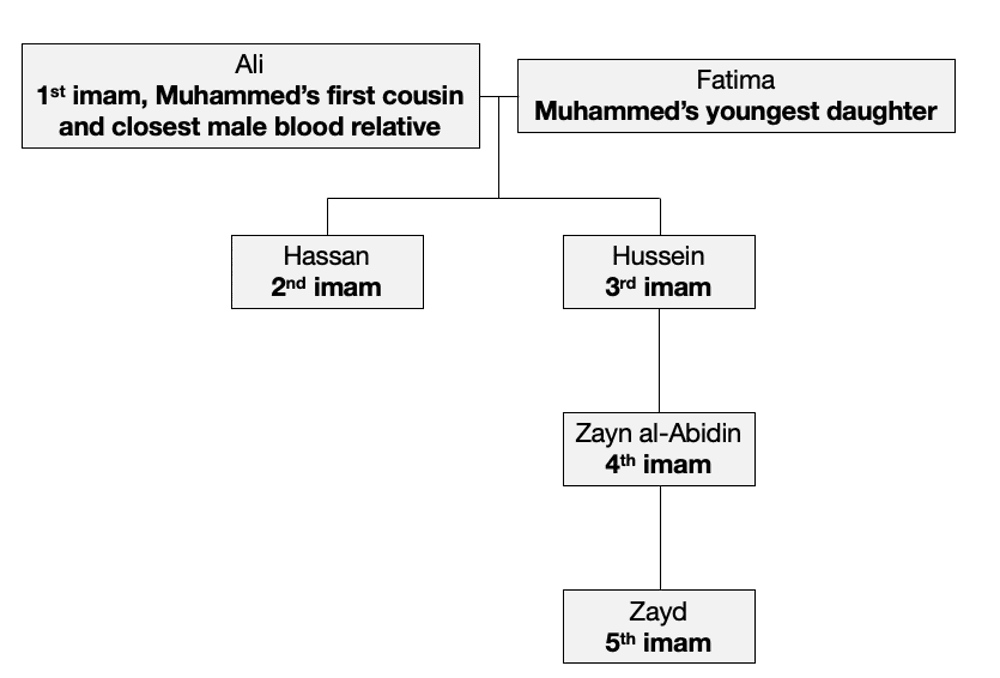

Shiites and Sunnis disagree about who should have been selected to succeed Muhammad as head of the Muslim community. Two groups emerged after his death. One group of the Prophet’s followers — later called Sunnis — recognized four of his companions as “rightly guided” leaders. In contrast, another group — later called Shiites — recognized only Ali, the fourth of these leaders, as legitimate.

Ali was the Prophet’s first cousin and closest male blood relative. He was also married to Fatima, Muhammad’s youngest daughter. For these and other reasons, Shiites believe that Ali was uniquely qualified to lead. In support of this claim, they cite sources describing Muhammad’s wish that Ali succeeds him. Shiites consider Ali second in importance only to the Prophet.

Zayd earned the respect of his followers when he rose up against the powerful Muslim rulers of his time, whom he believed to be tyrannical and corrupt. Though his rebellion was ill-fated, his fight against oppression and injustice inspires Zaydis to actively resist.

A key Zaydi belief is that only blood relatives of Ali and Fatima are eligible to serve as religious leaders, or imams. In Yemen, these relatives form a notable class of people called Sada. Hussein al-Houthi, the first leader of the Houthis, came from a prestigious clan of Sada.

Impact of sectarian differences

Not all Zaydis have a favorable view of Sada elites. When north and south Yemen merged in 1990, the republican government, led by a Zaydi president, sought to reduce their outsized influence and limit their privileges.

Some members of the Sada reacted to the country’s changing political landscape by joining electoral politics to secure honor and exercise power. This path was initially followed by Hussein al-Houthi but, after he decided it was ineffective, he abandoned it.

Other members of the Sada, particularly the youth, reacted by pledging to teach and promote Zaydism among their peers who had forgotten their ancestors’ religion. To accomplish this, they founded the Believing Youth organization and set up a cultural education program based on a network of summer camps in the north. Hussein al-Houthi joined this organization in the early 2000s and later transformed it into a political movement critical of the Yemeni government’s ties to the West.

Related: If Yemen’s Houthis weren’t Iranian proxies before, they could be soon

Security forces sent to arrest Hussein al-Houthi touched off the first war with the Houthis. Houthi was killed during the conflict and leadership passed to Hussein’s father and then to Hussein’s youngest brother, Abdul-Malik Badreddin al-Houthi, who helped transform the Houthi movement into a powerful fighting force.

Five additional wars followed over the next six years until, in 2010, the rebels had grown strong enough to repel a ground and aerial offensive launched against them by Saudi Arabia. During these wars, the Houthis pushed beyond their traditional base and captured vast sections of territory.

Many Yemenis, according to one expert, believe that the Houthis are fighting to restore a state like the one prior to 1962, led by imams who came exclusively from Sada families.

Complex factors today

Houthis continue to focus on protecting the Zaydi region of north Yemen from state control. However, they have also forged coalitions with other groups — some of them Sunni — unhappy with Yemen’s persistently high unemployment and corruption.

A 2015 UN Security Council report estimates that the Houthi movement includes 75,000 armed fighters. However, if unarmed loyalists are taken into account, they could number between 100,000 and 120,000.

Sectarian tension is only one factor in the complex set of interlocking factors responsible for violence and starvation in Yemen. But it is, without a doubt, a contributing factor.![]()

Myriam Renaud, is a principal investigator and project director of the Global Ethic Project, Parliament of the World’s Religions at the University of Chicago.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.