The Arctic’s Sámi people push for a sustainable Norway

A child carries a Norwegian flag on a high Arctic landscape.

This story comes to us through a partnership with the podcast and radio program Threshold, with funding support from the Pulitzer Center.

Here’s what a couple thousand extremely happy Norwegians look like: a long, jubilant river of men and women wearing traditional, colorful outfits called bunads and waving little red, white and blue Norwegian flags. It’s a stream of color flowing through the snowy streets of the high Arctic town of Longyearbyen, on the archipelago of Svalbard, as a band plays the Norwegian national anthem.

The marchers are celebrating Norwegian National Day. It’s an unabashed display of national pride in a country not always comfortable with the idea.

“I know some people may think that it’s like, ah … nationalistic,” said 26-year-old Kari Ellingsen. “But it’s not Norway for Norwegian[s] … It’s sort of, Norway for everyone. And I think it’s like a celebration of … human rights and freedom of speech.”

Those are values that Norwegians hold high. The Economist magazine currently ranks Norway as the most democratic country in the world, and Reporters Without Borders puts it at No. 1 on its World Press Freedom index.Norway is also among the richest countries in the world, mostly because of its massive offshore oil and gas reserves. But despite their national pride, that reliance on petroleum money is something many Norwegians have grown uneasy with. “Why should we just keep pumping up oil and … pretending to be [morally] superior to everyone, going, like, ‘Oh, we’re the happiest people in the world,’ while we’re drowning in oil?” asked Isalill Kolpus, a 27-year-old high school teacher in the Arctic city of Tromsø.

A few days before, the Norwegian government had opened up more than a hundred new areas for offshore oil and gas exploration, a move that dismayed Kolpus.“I don’t get it,” she said. “It’s such a bad choice.”

Norway doesn’t actually use much of the petroleum it pumps out from under the seafloor. Instead, it exports the oil and gas and uses the income to provide free health care and education and save for the future.

Related: Arctic permafrost is starting to thaw. Here’s why we should all care.

And the country wants that future to be more sustainable than the present. For its own energy needs, Norway relies mostly on much cleaner renewables. It also has set some ambitious climate policy goals, like aiming to phase out the sales of all new gas and diesel vehicles by 2025. Kolpus supports those initiatives, but she thinks Norway is trying to have it both ways — a reputation for environmental leadership and fossil fuel wealth. She says it’s time for the country to make a choice. “If we just make the decision and just go, ‘No, no more,’” and don’t open any more oil rigs, she said, “then we are forcing ourselves to look in the other direction.”

For Kolpus, one of those other directions should be toward her own roots. She’s Sámi, one of the Indigenous people of northern Scandinavia, and she believes that the rest of Norway could learn a lot from her people about how to shape a more sustainable future.

But she says there’s a long tradition of Norway ignoring or outright silencing Sámi voices.

“What is Norway?” Kolpus asked. “Norway is Vikings, and farmers, and the bunad. Everything Norwegian is this. And what did we decide was not Norwegian? Sámis.”

The Sámi are descendants of some of the very first people to enter the Scandinavian peninsula more than 10,000 years ago. They developed nine different languages and traded with each other across their Arctic homeland, which they call Sápmi.

Much more recently, other groups like the Vikings migrated into the region from the south. They built kingdoms that eventually became the nations of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, and as borders went up across Sápmi, Kolpus says her ancestors were viewed with suspicion.

“There was this thought that to create a nation, you have to have one language. … One language, one nation, one people,” she said. “That means if it’s not Norwegian, it doesn’t really fit our project right now. It’s like, ‘It’s not that convenient that you have a double identity. You have to choose one, and please choose the Norwegian one.’”

Related: In Iceland, a shifting sculpture for a changing Arctic

Sámi music and spiritual traditions were declared sinful, and Sámi children were forced to attend boarding schools. It was a colonization and Christianization process that will sound painfully familiar to many Native Americans and other Indigenous communities around the world, and it’s a legacy that carries on even today, often internalized among Sámi themselves.

“My grandmother, she has never really said that we are not Sámi,” said Susanne Amalie Langstrand-Andersen, who helps organize an annual celebration of Sámi culture in the mountains of northern Norway, called Márkomeannu. “But 10 years ago when we went to the store, she would not speak Sámi in the store in any way, because other people could hear her.”

Kolpus recalls a similar sentiment in her family when she was growing up. No one talked about the fact that they were Sámi.

“It’s such a weird thing,” she said, “because I’ve always known because my last name [is] an old Sámi name. And so I’ve always known, and I’ve always heard my grandmother and my grandfather talking Sámi. But I didn’t really realize it or understand it until I was like 18.”

That was when one of her cousins started wearing a gakti, the traditional Sámi dress. It was part of an awakening to her own culture.

“And I was like, ‘Oh, oh, that’s right. We’re … we’re actually Sámi.’”

Later, Kolpus received her own gakti from an elderly relative.

Related: These Sámi women are trying to keep their native Skolt language alive

“It’s the most beautiful piece of clothing I’ve ever seen,” she said. “I think it’s 80 years old, but it’s like the colors are still so … vivid.”

Kolpus started sharing pictures of herself wearing the gakti on social media and sometimes writing posts in Sámi.

Lots of people were supportive, but not all. She says she started getting passing comments from friends, like, “‘Oh, she’s Sámi now.’ Which you hear a lot when you when you’re a part of the Sámi population who are reclaiming. You hear a lot of, “Oh, you’re Sámi now.” And you go, ‘No, no, I’ve always been Sámi.’”

Like Kolpus, Langstrand-Andersen often wears the gakti. But when she’s not wearing it, she could be mistaken for any other Norwegian, and that’s one of the complexities of being Sámi — you can hide your heritage if you want to. You can blend in.

The flip side is that sometimes you’re not recognized as Indigenous even when you want to be. And these days, a lot of Sámi want that recognition.

“I have been traveling to a lot of international UN meetings, and I always get that question — ‘Are you really Indigenous?’ — because I’m white,” said Langstrand-Andersen. She says she even gets the question from other Indigenous people. “And I can understand them because they have a different story about colonization.”

But things are changing. Sámi people are increasingly making themselves seen and heard in all sectors of society.

“There [is] really a fighting spirit in Sápmi now,” Langstrand-Andersen said. “You see that through art and music, that most of the art and music is about that we are still here. It’s very political, most of the art and the music, and nearly every cultural expression right now. Maybe you couldn’t see that as much 10 years ago.”

For Kolpus, reclaiming her Sámi identity has meant becoming more politically involved, especially around environmental issues.

Even that, though, means negotiating stereotypes.

“A lot of people say, ‘Oh you’re Indigenous, and you must be in touch with nature,’” she said. “Yeah, maybe. But I hope that I would care about the same issues even if I wasn’t Sámi. But it’s a fact that a lot of Sámi culture is intertwined with nature, and a lot of our expressions are based in how we used to live very close to nature. And some of us still do.”

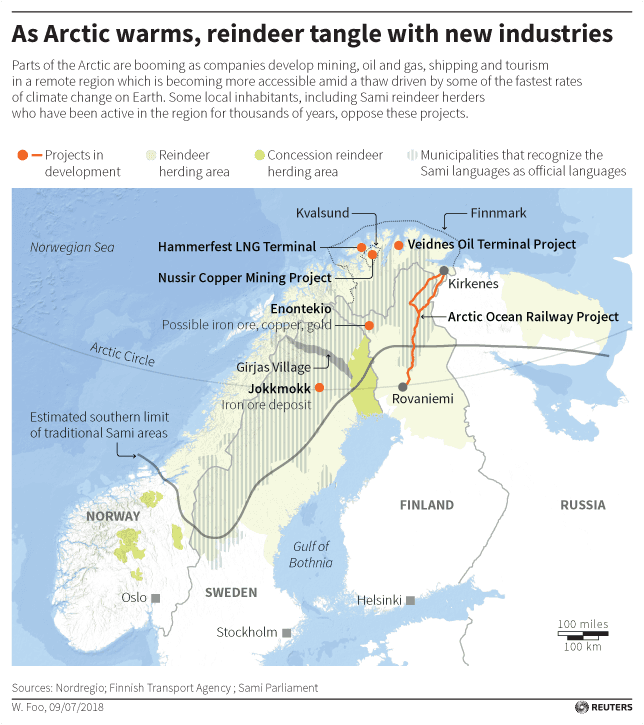

Kolpus says Sámi communities are fighting the expansion of mines, railroads, logging operations and even wind farms that could disrupt local reindeer-herding operations.

Related:This family is already being hurt by climate change. They might also be hurt by a solution.

She says many Sámi people are very concerned about the impacts of oil and gas development, as well. Among other things, climate change caused by carbon pollution from fossil fuels produced by Norway and other countries is harming Sámi reindeer herders, because the warming Arctic has brought more rain in the winter. That means more ice, which reindeer can’t dig through to find the lichens and plants they need to survive.

But it’s not just rural Sámi who are concerned about the impacts of climate change and other environmental problems.

“Me, I’m like what you call a ‘city Sámi,’” Kolpus said, “or like, an ‘asphalt Sámi,’ is like the derogatory term. But we have a lot of issues that affect us as a people, as a culture; at the same time, it affects nature. In that way, my Sámi identity and the part of me that cares about the environment is two sides of the same story.”

As more Sámi reclaim their cultural identity, many of them see their situation in a global context. They’re connecting with other Indigenous movements, like the anti-pipeline protesters at Standing Rock in the US.

There are also Sámi parliaments in Sweden, Finland, Norway and Russia, with varying degrees of power.

“We have information about the entire planet,” said Anne Henriette Reinås Nilut, the youngest member of the Sámi Parliament of Norway, at 24. “And that demands of us that we change the way we think and that we learn to think holistically.”

Reinås Nilut carries around a MacBook laptop bearing a sticker with a Sámi version of Rosie the Riveter.

“People think that Indigenous people and Sámi people are something we read about in a history book,” she said. “But it’s not. It’s so important to let the Indigenous people of the world tell the rest of the world how to live with nature instead of against nature.”

As one example, Reinås Nilut says instead of fixating on our national identities, we need to start thinking of ourselves as one species with common interests and a shared fate.

“This way this world is organized, that does not fit with the Indigenous thought. … We are people, living on a planet,” she said. “We have different ways of living, but none of us are above or superior to another group of people who have another way of living.”

This is not to say Reinås Nilut believes the Sámi have all the answers. She says just like any other group of people, there’s great diversity of opinion and approach within the Sámi community. And she warns against reducing the Sámi or any Indigenous group to some kind of mystical heroes whose ancient wisdom is going to save the rest of us from environmental disaster.

Her message is more practical than that.

“Just look around you. The big society is clearly not doing a great job of taking care of this planet. Of course, we should listen to Indigenous people. Of course,” she said.

For Reinås Nilut, being Indigenous is as much about building the future as it is about honoring the past. And she says it’s foolish to think we’re going to solve climate change using the same ways of thinking that created the problem. In her opinion, we have to open up to other worldviews.

“This holistic way of thinking that exists today … it’s very much alive in the Indigenous groups. I think that’s the only way forward.”

Amy Martin is the executive producer of the podcast and radio program Threshold.