Immigrants have a long history of taking their issues to the people — as political candidates

Farousa Jama, a candidate for city council, speaks at a community breakfast event in Mankato, Minnesota, in the summer of 2018. The Somali Community Barwaaqo Organization, which Jama and her father, Hussein, founded, organized the event.

On a cold, January afternoon in 2017, Fardousa Jama went to a coffee shop in Mankato, Minnesota, where activists and elected officials assembled to devise a plan to show solidarity with local refugees. President Donald Trump had just signed an executive order that barred travelers from certain predominantly Muslim countries from entering the US.

Jama came to the US as a refugee from Somalia and has lived in Mankato, a college town about an hour southwest of Minneapolis, for two decades. She expected the discussion would focus on plans to contact US senators and representatives about the issue, assist residents whose families were affected by the order and assure immigrants that they’re welcome in the city.

That didn’t happen.

Jama, 33, says a state legislator told the crowd at the event that wearing a hijab would be one way to show solidarity with the Muslim community, though not all Muslim women choose to cover their heads in observance of Islam.

“I was kind of angry at that,” Jama says. “You are not connecting with us if that’s the only advice you can give us as a way to show support.”

That was the beginning of Jama’s journey to run for a seat on Mankato’s city council. She is challenging 16-year incumbent Mark Frost in a closely watched race.

In Minnesota, a record number of immigrants and children of immigrants are running for election this year for local, state and national positions, in part to combat increasing anti-immigration and Islamophobic sentiments and to give their communities a voice in politics.

In primary elections in August, Jama was one of at least 10 Somali American candidates in Minnesota, according to an unofficial headcount. Several, Jama included, advanced to the November elections.

Among those candidates are state Rep. Ilhan Omar, poised to become the first Somali American elected to US Congress; Mohamud Noor, who will likely replace Omar in the state legislature; Hodan Hassan, who is also running for a seat in the state legislature; and Siad Ali, who is seeking re-election to the Minneapolis School Board.

If elected, or re-elected, these candidates will join the ranks of four currently sitting Somali American officials, all elected since 2013: Abdi Warsame, a member of the Minneapolis City Council; Abdikadi “AK” Hassan, a commissioner on the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board; Fartun Ahmed and Abdi Sabrie on two school boards. Come November, that number is likely to rise to eight — Omar, Noor, Hassan and Ali are favored to win their races in the general elections.

It’s not just Somali immigrants and their children who are running. Nine Hmong Americans and at least four Liberian Americans will appear on the November ballot in Minnesota. Among them, Samantha Vang is seeking a seat in the state legislature; Paul Yang and Adam Yang are running for judicial seats; and Blong Yang is vying for a county commission seat. Two of the Liberian immigrants running for office are Mike Elliott, running for a spot as a suburban mayor and Wynfred Russell, who is seeking a spot on a suburban city council.

From the 2016 election: These elected officials are among the few who were born outside the US

Sayu Bhojwani, founder and president of New York-based New American Leaders, a nonprofit organization that recruits and trains immigrants and their children to run for office, says a similar trend is at play in cities and towns across the nation. While there is no official record, her organization has tracked at least 100 immigrant congressional candidates who are running nationally this year, more than they’ve seen before.

Among those who have advanced to the November election is Colombia-born Catalina Cruz, who was once an undocumented immigrant. She is poised to join the state legislature in New York.

Bhojwani says candidates like Cruz and Jama want to resist the Trump administration’s anti-immigration policies. They are also bolstered by organizations that have emerged to recruit and support immigrants to run for office since the 2016 presidential elections.

Bhojwani’s group is one of those organizations. In Minnesota, Reviving the Islamic Sisterhood for Empowerment, African Immigrant Services and the Community Equity Pipeline also offer political and civic engagement training to underrepresented communities.

“Across the board, there are more resources available to political newcomers,” says Bhojwani.

Common immigration experience

Whatever the reason, the stories of immigrants and refugees rising to political leadership is not new in Minnesota.

In his latest book, “Scandinavians in the State House,” journalist Klas Bergman chronicles the histories of Nordic immigrants who arrived in Minnesota in the 19th and 20th centuries. Like Somalis, Hmong and Liberians, these Norwegians, Swedes, Danes and Finns first held office as city council members, county commissioners and sheriffs.

Later, they advanced to occupy more prominent political seats. They became mayors, state senators and representatives, as well as members of the US Congress. Eric Hoyer and James Gray, born in Sweden and Scotland respectively, served as mayors of Minneapolis in the 1900s.

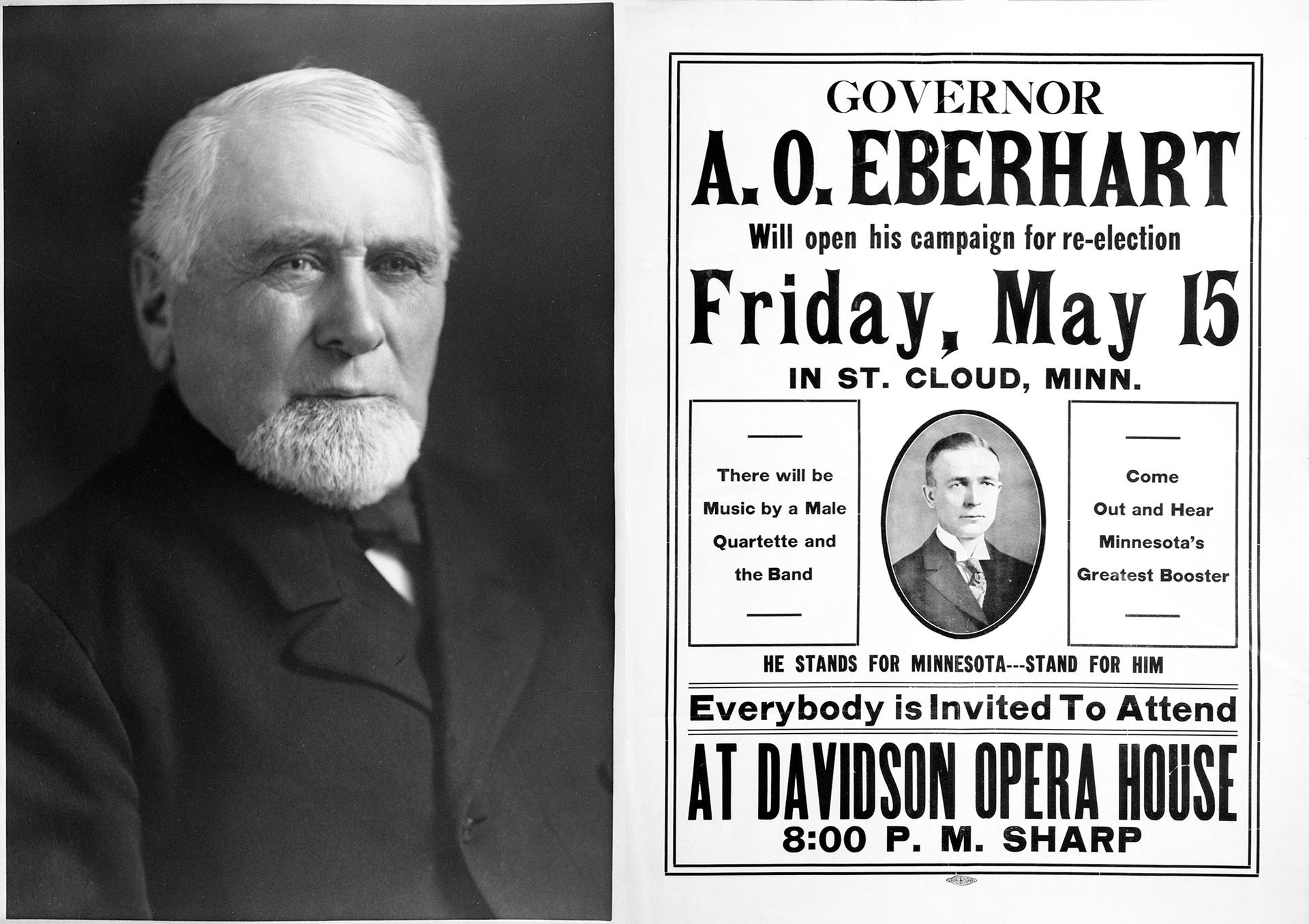

Likewise, Norway-born Knute Nelson, Sweden-born John Lind and Adolph Olson Eberhart and Denmark-born Hjalmar Petersen all served as governors of Minnesota in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“They wanted to participate in politics for various reasons,” Bergman says. “One strong reason was the wish to be part of their new home country by becoming involved in civic affairs. They landed in a new country and this new country needed them, and they got involved.”

Bergman also says Scandinavian immigrants were sometimes the only people living in certain towns in Minnesota — they had to play leadership roles to maintain those towns.

“For instance, they were the only ones who had to deal with water and electricity problems. They had to take care of the schools and the churches and the roads.”

And like those Scandinavian immigrants, today’s immigrants and their children have many reasons to become leaders.

“A lot of us who are second-generation immigrants feel like our parents passed the baton and we’re starting from a different starting point,” says St. Paul council member Mitra Jalali Nelson, who in August became the first Iranian American elected to office in Minnesota. “So they might not have the understanding of these systems, but we do.”

And sometimes, it’s the parents who encourage their children to get involved in their adopted country’s politics. After that meeting at the Mankato coffee shop, Jama returned home, disappointed in what she saw as a weak response to immigration policies.

When she talked to her father, Hussein, about her frustration, he told her something that redefined Jama’s career: “If you want something to be changed,” said Hussein, who died recently, “you can’t wait for somebody to invite you to the table. You have to invite yourself to the table.”

Four months later, Jama filed to run for a city council seat in Mankato.

“After the conversation with my dad,” Jama says, “I said, ‘I don’t have any experience at the state level, but what I can do and what I can change is the perspective of the residents of Mankato and how they view immigrants and refugees.’”

This story was produced in partnership with the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota. Indra Ekmanis contributed to the report.