For this nurse trained abroad, working at a US hospital is years away

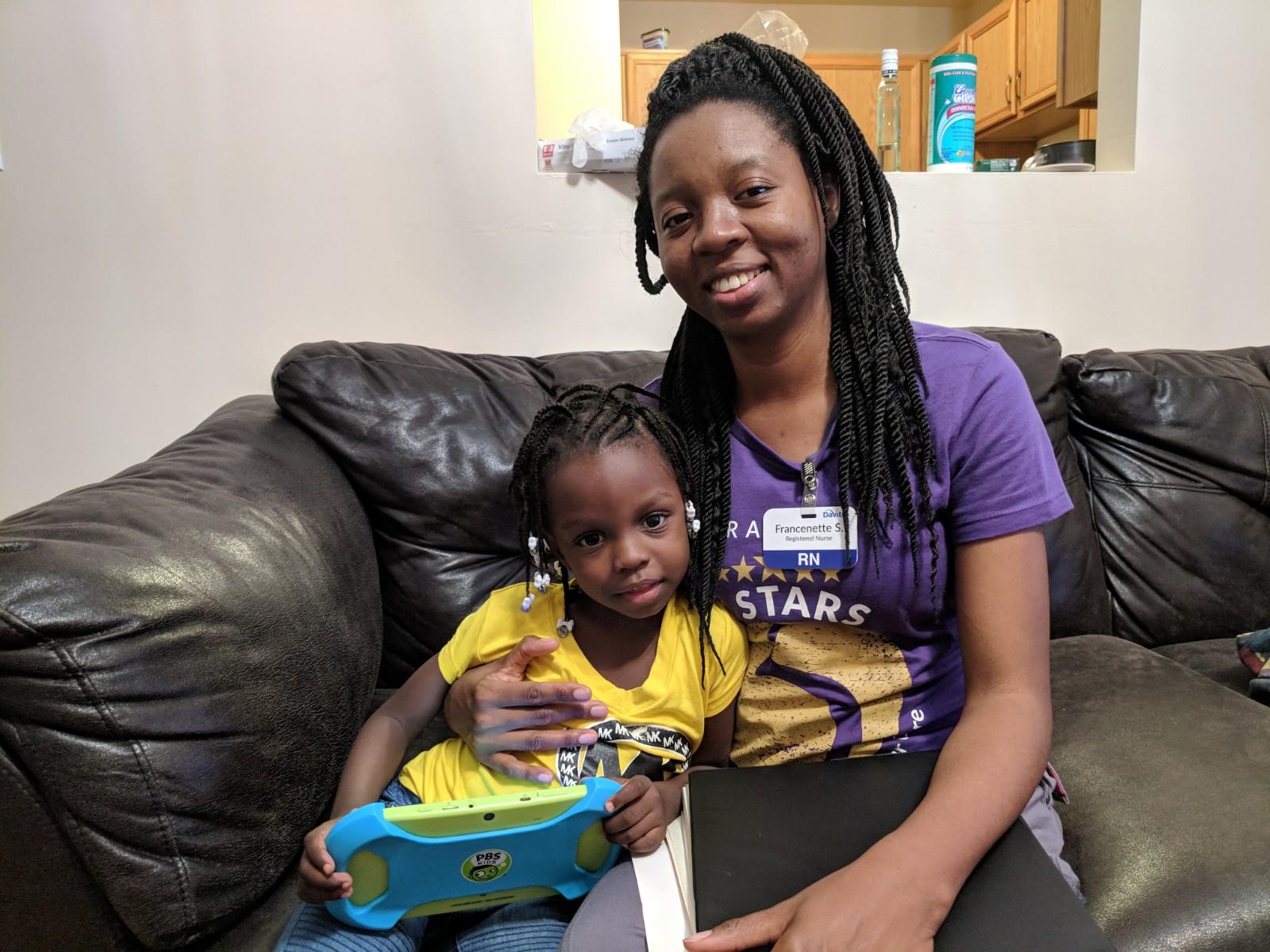

Francenette SaintLouis Défonce shows certificates from her years of schooling and her US nursing certificate at her home in upstate New York on Sept. 29, 2018. But she can’t use that experience in the US until she passes a licensing exam and finishes a bachelor’s degree.

When she was young, Francenette SaintLouis Défonce visited several hospitals in Haiti with her mom. Her mother was sick and often in pain, so they would go from doctor to doctor to see if someone could figure out what was wrong. During these visits, Défonce noticed how the people at the hospital worried about her mother.

“And when I saw there was a lot of people that needed care,” Défonce remembers. “I said, ‘Let me be a part.’”

Défonce went to school — three years to train as a nurse and then a year and half more to become a certified midwife. Then in 2010, soon after she got her certification, a massive earthquake struck Haiti. Défonce was dispatched to areas where there were few doctors. She worked with international medical teams and cared for women who were infected with HIV, and delivered their babies.

“I saw people died in labor and delivery, when someone cannot afford care,” Défonce says. “We lived a lot of things.”

Défonce felt like she found her calling.

Then in 2016, she moved to New York to be with her husband. But in the US, nurses are required to be certified through state licensing exams. Francenette had left her country and her career behind.

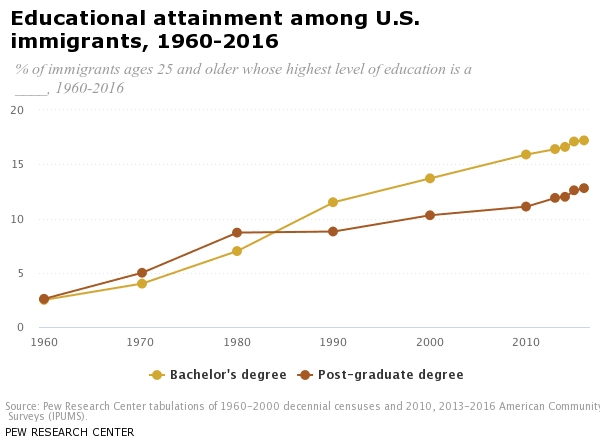

Immigrant workers in the US today are more educated than ever before. According to a study by the Pew Research Center, they are just as likely to hold bachelor’s degrees as US citizens. But often that education doesn’t translate into similar careers as citizens. And passing qualification exams — like the ones required in nursing — can be inordinately difficult.

At the same time, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics have been warning of a coming nursing shortage. The US needs to certify 1.1 million additional nurses in the next four years to keep up with the health care needs of the aging population. In the past few years, colleges across the country have started programs to help foreign-born nurses enter the healthcare industry. Still, many immigrants who already work other jobs and have families have a hard time going back to school.

Welders, physicians, and parents: How do immigrants get educated? Read and hear more in Brain Gain.

One program at LaGuardia Community College, in New York, is helping immigrant nurses pass one important hurdle: the nursing exam.

“We are preparing nurses to reclaim their career, their status, self-esteem,” says Tania Ramirez, an educational case manager at LaGuardia Community College’s Welcome Back Center in Queens, New York.

The program, which started at the center three years ago, is an eight-month course that prepares students to pass the NCLEX-RN, the national certification exam for nurses in the US and Canada. The exam is a massive, hours-long test of a nurse’s knowledge and ability to make medical decisions.

Eighty-seven percent of US-educated nurse pass the first time, but only 40 percent of nurses educated abroad make it through. And they make up 8 percent of the 172,000 people who took the exam for the first time in 2017.

Ramirez says it’s important for more immigrant nurses to take the exam and pass, though, because New York too is affected by the nursing shortage.

“There’s a loss of skill and knowledge and talent that we would be missing out if these nurses weren’t licensed and working in their field,” Ramirez says.

When Défonce arrived in New York in 2016, she started working as a home health aide, helping elderly or invalid patients with their meals, medication and doctor’s visits. Défonce knew about the NCLEX, and she knew about the low passing rate for immigrant nurses with intermediate English, like her. Another nurse told her about LaGuardia’s NCLEX program. She applied and got in.

But the program is strenuous, four days a week, six hours a day, for eight months.

At the time, Défonce’s husband was finishing up his time in the US Army at a base in Florida, and their daughter, Kenette, was only 2. Défonce knew that she would be working as a home health aide on weekends and studying during the week and would have no time to take care of her daughter. So she took Kenette back to Haiti to stay with her grandmother while she finished the program.

“So I sacrificed my family to be able to finish the program,” Défonce says.

In a small classroom on a Tuesday night in July, about 15 women from all over the world — Nepal, China, Honduras and Haiti — sit at desks, NCLEX prep books open, paragraphs highlighted in pink and yellow.

The instructor, Phil Gimber, a registered nurse, runs through the stages of renal failure and goes over sample exam questions. As Gimber talks, another instructor writes out difficult words like “creatine,” “ketones” and “diluted” on a long white sheet of butcher paper. LaGuardia’s program is unique in that it integrates English language and nursing instruction.

Gimber believes that language is one of the main reasons for the low passing rate among immigrant nurses. For example, he says, one of the questions on the NCLEX asks what a nurse should do for a patient who has a high risk for bleeding.

“And the answer is: Encourage them to wear a thimble when sewing.” The problem is not the concept, Gimber says, but the vocabulary. “They know the idea — a needle is sharp, of course — but they don’t know what a thimble is.”

Also: Highly trained and educated, some foreign-born doctors still can’t practice medicine in the US

Getting into LaGuardia’s program is highly competitive and 75 percent of the immigrant nurses who finish pass the NCLEX. Including Défonce.

She finished the program in the fall of 2017, passed the NCLEX and officially became a nurse. But then she discovered another hurdle to pursuing her life’s calling.

Défonce wanted to work at a hospital, delivering babies and taking care of women. She took her nursing certificate and went hospital to hospital looking for any job in a maternity ward. But a New York state law adopted in 2017 requires all nurses to have a bachelor’s degree. Défonce has four and half years of college — three years of nursing school and one and half years of midwife training — but the US only counts the nursing school.

So, Francette registered at City College in New York to finish about 30 credits and get a bachelor’s degree in nursing (again). It’s a process that she thinks will take about five years because she currently works full-time.

“No, I never stop,” Défonce jokes one evening, sitting on her couch in the soft pink scrubs from the dialysis lab where she works. “Never, never stop. I want to go forward.”

In June 2018, Défonce became a US citizen. In the fall, Défonce, 34, accomplished one more thing: She brought her daughter, Kenette, back from Haiti. Kenette arrived a few days before her fourth birthday.

After work one Saturday, Mustapha, Défonce’s husband, makes a huge pot of stew, and Kenette rides her pink bike up and down the carpeted hallway. Défonce cheers her daughter on.

“How old are you?” she asks Kenette in French. “Four!” the little girl shrieks.

Défonce worked 12 hours that day, and she has some assignments to finish for her class before she goes to sleep. But she says she’s thinking of five years from now, when she’ll be working in a hospital as a nurse.

Next: Upskilling’ programs are helping immigrants use their work experience

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?