When 25-year-old Aye Aye Dun was a kid, she spent most weekends in the backseat of her parents’ car, riding from small-town Springfield, Missouri, to bigger cities with Buddhist monasteries, meditation centers or Burmese family friends who hosted big picnics.

Springfield, Illinois, was a six-hour drive. Oklahoma City was a four-hour drive.

On the way, her family listened to oldies on the radio or Buddhist sermons on tape. They drove to worship with monks visiting from Myanmar, formerly called Burma, and to sit with other Burmese Americans over plates of si htamin, oily, glutinous rice with onion and turmeric, baya kyaw, split pea fritters, and classic mohinga, catfish noodle soup topped with fried crunchy garlic and peas, cilantro and lime. When a monk was visiting, Dun’s parents encouraged her to speak with him one-on-one.

Dun remembers sitting on the floor and looking up at her religious leaders, wrapped in dark red robes with shaved heads, in reverence.

Guidance from Buddhist monks, Burmese food and community weren’t available in Springfield, where her parents moved for work after they immigrated to the US from Myanmar. The middle-America town was so predominantly white and Christian, Dun says, that her mom later told her that when she saw an ethnic-sounding name on her class roster, she would get excited because she wanted Dun to have someone to relate to. Dun’s parents worried their family’s Buddhist traditions might be washed away by assimilation to white, Christian norms.

So each night before bed, they had Dun memorize sutras or read stories from the “Illustrated History of Buddhism.” Dun loved seeing her religious texts brought to life with bold, vivid illustrations. There was the story of Prince Ajatasattu, for example, who gets tricked into imprisoning his own father and then orders the soles of his feet to be sliced with a knife. The prince only realizes his mistake when he has a child and recognizes the unconditionality of a father’s love.

“The main takeaway I remember from the stories,” Dun says, “is that going against your parents is the worst thing you can do.”

In 2012, when Dun was 18 years old, she started hearing about a Buddhist monk who was spreading vitriol and hate against the Rohingya, an ethnic minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. She came across Time Magazine’s cover story about “the Buddhist bin Laden,” Wirathu, a monk accused of inciting violence against Muslims in Myanmar.

“Nonviolent, virtuous monks who would protest against corruption and injustice and despotic government. That was, like, my image of Burma,” she says. Wirathu changed Dun’s understanding of her religious leaders.

One night, Dun sat down to dinner with her parents and asked them about Wirathu and the crisis in Rakhine state. She was shocked by their impassive response: They told Dun not to challenge Wirathu, that there’s a lot of misinformation about the situation in Rakhine state.

“I felt such a dissonance, like, these are not the people who raised me,” Dun says. “It was very jarring.”

More about the Rohingya: Over a million plead have fled a brutal military campaign, which the United Nations calls “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

It was jarring mostly, Dun says, because the xenophobia toward the Rohingya she heard from her parents sounded similar to the xenophobia toward immigrant communities she saw in the US. Burmese Americans are one of the most economically marginalized Asian minority groups in America, and Dun says Burmese people in the US are often looked down upon not only by Americans, but by other Asian minorities. It was painful to see Burmese immigrants with similar prejudices.

But the breaking point was when someone in her community — Dun won’t say who — told her that if she encountered Wirathu in public, she would have to bow to him.

“Someone who I loved and respected, who helped me maintain my heritage, told me that I’d have to do that,” Dun says. “I was shocked.”

That shock turned into shame and guilt. By challenging a monk, Dun felt like a traitor. As she continued attempts to engage her family in conversations about the Rohingya, she says she was made to feel like she was turning her back on her own people.

“Turning my back on my culture and identity, [like] I shouldn’t even call myself Burmese because I support the Rohingya,” Dun says. “Nothing hurts more than when that comes from people who are close to you, who made you the person you are.”

Dun wanted to divorce herself from her Burmese-ness. But then, in her 20s, when she was in graduate school at New York University, she became reacquainted with her identity in a new way via friendships with other Burmese Americans. One of those friendships was with Aye Min Thant, a West Coast woman her age. They had initially found each other virtually while in college on the networking site Tumblr. A group of Burmese Americans was posting pictures of what their parents packed in their school lunch boxes and chatting about other moments of cultural clashes.

By the time Dun began seeing Wirathu in the news, both women had stopped using Tumblr, but stayed in touch. After several upsetting conversations with her parents, Dun called Thant. The two stayed on the phone for hours reassuring each other that they aren’t betraying their culture by challenging monks and their parents. They discussed politics and things they wished they could say to their parents in a calm, sit-down conversation. And later, after Myanmar military raids on Rohingya towns in Rakhine State in August 2017, they decided to make a video that would show a younger generation of Burmese Americans speaking to their elders about Myanmar’s injustices toward the Rohingya.

“That’s what got Saddha started,” Dun says.

Dun and Thant spent months crafting a video that later became the foundation of their organization, Saddha: Buddhists for Peace. In Myanmar, people who publicly show sympathy toward the Rohingya can face jail time, death threats and other hateful messages. The women were afraid of hate speech, but Dun says being American is a privilege that enabled her to criticize Myanmar without fear of physical harm. Hundreds of thousands of people watched the video in 2017. Months later, the women wrote an open letter to their community insisting that Buddhists speak out about atrocities against the Rohingya, no matter how difficult. Burmese Buddhists and their allies from all over the world initially signed the letter.

Rohingya in Chicago make an emotional plea: ‘Help our people’

Kenneth Wong, one of 77 people who initially signed on, is a Burmese-language lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of “A Prayer for Burma.” Wong moved to the US from Myanmar almost 20 years ago and says that while opinions among Burmese immigrants in America are diverse, there’s a strong camp of Buddhist Burmese immigrants who won’t engage in conversations about the Rohingya, even if they empathize with the Rohingya plight. Mentioning Rohingya can split an entire community, he says.

Wong offers this example: If someone is fundraising to build a new monastery or pagoda, and they mention the situation in Rakhine state, half the community might not show up.

“It’s not the sort of thing we can agree to disagree on,” Wong says.

That’s because many Burmese immigrants are loyal to State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, who has downplayed the Rohingya crisis, Wong says. (Two journalists who exposed Rohingya mass graves were jailed in September under her leadership.) Many of these immigrants are former political prisoners or people who were persecuted during Myanmar’s 1988 pro-democracy movement against a totalitarian regime. During that time, Suu Kyi was put under house arrest, awarded a Nobel Peace Prize and emerged as a national icon and symbolic mother-savior of Myanmar.

“Mother may have some poor judgment and mistakes,” Wong says, mimicking her supporters, “but by God, you must come to your mother’s defense when someone publicly criticizes her.”

To understand how to breach this taboo topic in their own communities, Dun and Thant turned to other religious movements whose leaders reject violence and persecution. One of those movements was Jewish Voices for Peace (JVP).

Dun and Thant took cues from JVP’s social media strategies, specifically drawing from JVP’s commitment to providing a community of support for American Jews who reject Israel’s occupation of Palestine. Executive Director Rebecca Vilkomerson says there’s a high price for people who challenge conventional attitudes toward Israel; some who disagree with their families about Israel’s policies are disowned or can’t find synagogues to pray in.

“In this type of organizing, you’re asking people to leave a comfortable community,” Vilkomerson says. “So you have to offer them a new one.”

By the time Saddha’s video gained traction, the group had hundreds of online followers. Commenters on the Saddha page wrote that Saddha supporters were traitors who accepted funding from wealthy Arab countries and damaged the image of Buddhism globally. Thant became a journalist and stopped working with Saddha in early 2018. But Dun has continued to cultivate support for Saddha, and has found other Burmese Buddhists from around the world who supported Saddha’s message.

Dun says building Saddha made her feel less lonely. She found out that she wasn’t the only who was afraid of being shunned or ostracized, or of not making an impact.

“At first we were so tentative with what we would say, but with new friendships and alliances we’ve made, I definitely feel bolder with my criticism or discourse with others on this topic,” Dun says.

Most importantly, Dun says Saddha was built on the principle that people are capable of changing — even people who seem steadfast in their understandings of the Rohingya crisis, like her own family members. Two years ago, Dun and her family visited Myanmar together. Dun remembers visiting famous pagodas with her father where locals asked him, “What are you?”

The question irritated her father. It implied that Burmese people didn’t assume he was Burmese. Dun compares it to her own experience of being “othered” by her classmates in Missouri; she thinks that her father’s experience of being “othered” by Burmese people made him more open-minded.

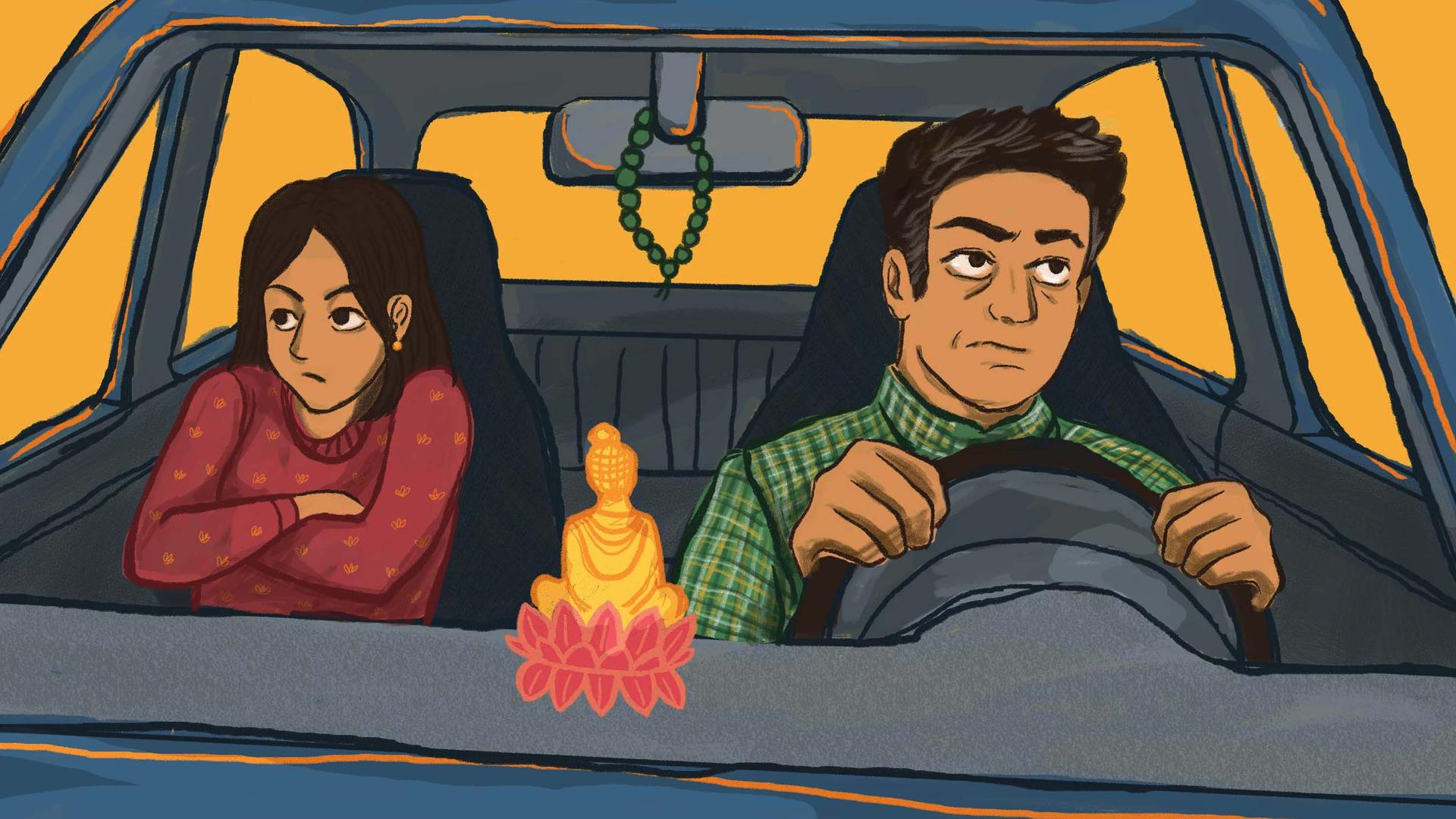

Later, she and her father were in a taxi in Yangon and her father asked the driver what he thinks about the Rohingya issue. The taxi driver said that in Myanmar, there are many ethnic groups being oppressed and that the Rohingya are just one of them. Dun’s father nodded his head in agreement.

“It was a pleasant surprise,” Dun says. “That is one of the fondest memories I have of being in Burma.”

This story was corrected to include Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s correct title.

Next: Her cousin was killed in a school shooting, but this exchange student decided to stay in the US