Despite the heat and hour-long drive, hundreds traveled in packed school buses to downtown Chicago as part of a protest organized by the Rohingya Cultural Center Saturday, Sept. 23, 2017.

The young man holds the piece of paper up over his head, facing a crowd on a Chicago sidewalk, his brow furrowed underneath a white headband bearing “ROHINGYA” in bright red letters. On the paper, there are two pictures: one of an elderly man with an orange beard, sitting stoically for the camera in a white robe. The other picture: a charred body.

“This my father,” he screams toward a stream of pedestrians, many of whom don’t look up. His voice cracks and his bottom lip quivers. “They kill him. I have proof.”

This Rohingya man living in Chicago, who declined to give his name out of concern for his family in Myanmar, was one of hundreds who took part in a demonstration on Sept. 23. Protesters hoped to call attention to the state-sponsored ethnic cleansing campaign that is displacing hundreds of thousands of members of one of Myanmar’s ethnic minorities.

There have been reports of mass killings, rape and other atrocities against the Rohingya, largely committed by Buddhist extremists and with the support of Myanmar’s military.

News of the horrors has reached around the world but has hit especially close to home in Chicago, where more than 1,000 Rohingya live on the city’s far north side. It’s among the largest Rohingya communities in the US, many settled there after living in limbo in Malaysia for years. With the help of an Islamic group, called the Zakat Foundation, the Rohingya Cultural Center opened its doors in 2016. The storefront center was established to be a touchstone and resource for the city’s growing Rohingya population, most of whom were resettled as refugees within the last five years. Volunteers at the center help with English classes, job placement and general support in navigating life in the US.

But in recent weeks, it’s become a place to amplify the voices of the Rohingya in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. Members of the organization are looking to help their kin even as they themselves struggle to establish lives in the US.

“Right now, for us, raise voice is important,” says Nasir Zakaria, a Rohingya refugee who came to Chicago four years ago and is now president of the Rohingya Cultural Center. “If, for example, if I invited everyone [to protest], some community member, they take off day, they lost $100. They say, ‘Oh it’s nothing. Money not important.’ Right now we try to save our people in Burma, the important [thing] is raise voice for people.”

Zakaria’s own parents and seven brothers still live in Myanmar. The situation there causes anxiety and a feeling of helplessness within the community, especially because most of the Rohingya in Chicago still have immediate relatives in the country.

“Right now they are safe,” Zakaria says. “They stay at home only. They not allowed to go anywhere. They’re scared. Only waiting, if they say ‘attack’ to kill. No chance at life right now.”

A 25-year-old man named Abdul Samad says he isn’t sure if his mother and two sisters are safe in Myanmar.

“Because every day is burning villages, every day is killing people, killing children, raping women,” he says. “I don’t know, today is life, maybe tomorrow they will die, so I’m not sure.”

Omar Husin says his family members also need help.

“Maybe five people killed,” says Husin. “I have another three sisters and two brother. Big family. They crying, they need help from me. What can we do?”

The day of the demonstration, the Rohingya Cultural Center organized buses to transport more than 200 of the city’s Rohingya — many of whom took time off from work — from Chicago’s far north side to the city center. Participants marched, distributed pamphlets and gave impassioned speeches begging the US and United Nations to help their people.

Local politicians, a representative of the Turkish consulate, and activists — including the president of Chicago’s Syrian Community Network — also spoke in solidarity.

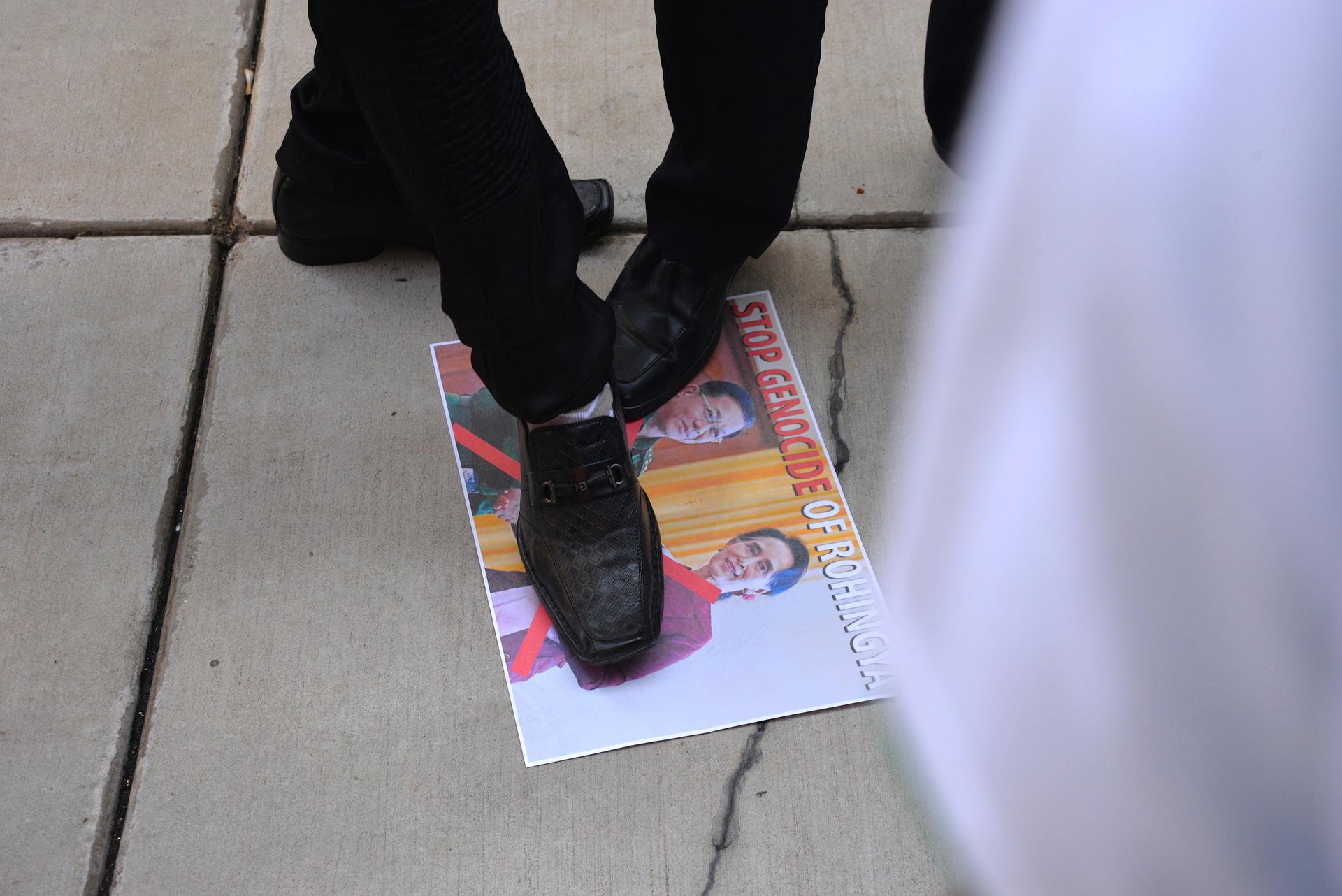

At times, anger became palpable, especially toward Myanmar politician and Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, whose inaction on the humanitarian crisis has drawn international condemnation. At the Chicago demonstration, furious protesters ripped up her photo or stomped on it.

Zakaria says the group also wants to send a message to the American people: Don’t look away. Myanmar may be far away from Chicago, he says, but we are your neighbors and these are our families.

“We raise our voice from here, fight back to Myanmar government,” he says. “We just waiting for government of United States. We just pray, please help us, help our people.”

He added, “We see only a power country. Why are they silent?”