Looking for stories of Russia beyond Putin? This artist has the answer.

Russian author Victoria Lomasko.

If you’re among those who feel press coverage of Russia has an unhealthy fascination with all things Vladimir Putin, then enter artist Victoria Lomasko’s “Other Russias” to the rescue.

That plural is no accident. Lomasko is out to capture Russian stories that most in the West never see.

“It was important to me over the last years to make a portrait of the unofficial face of the country,” Lomasko tells The World. “That part that we almost never hear from in the media.”

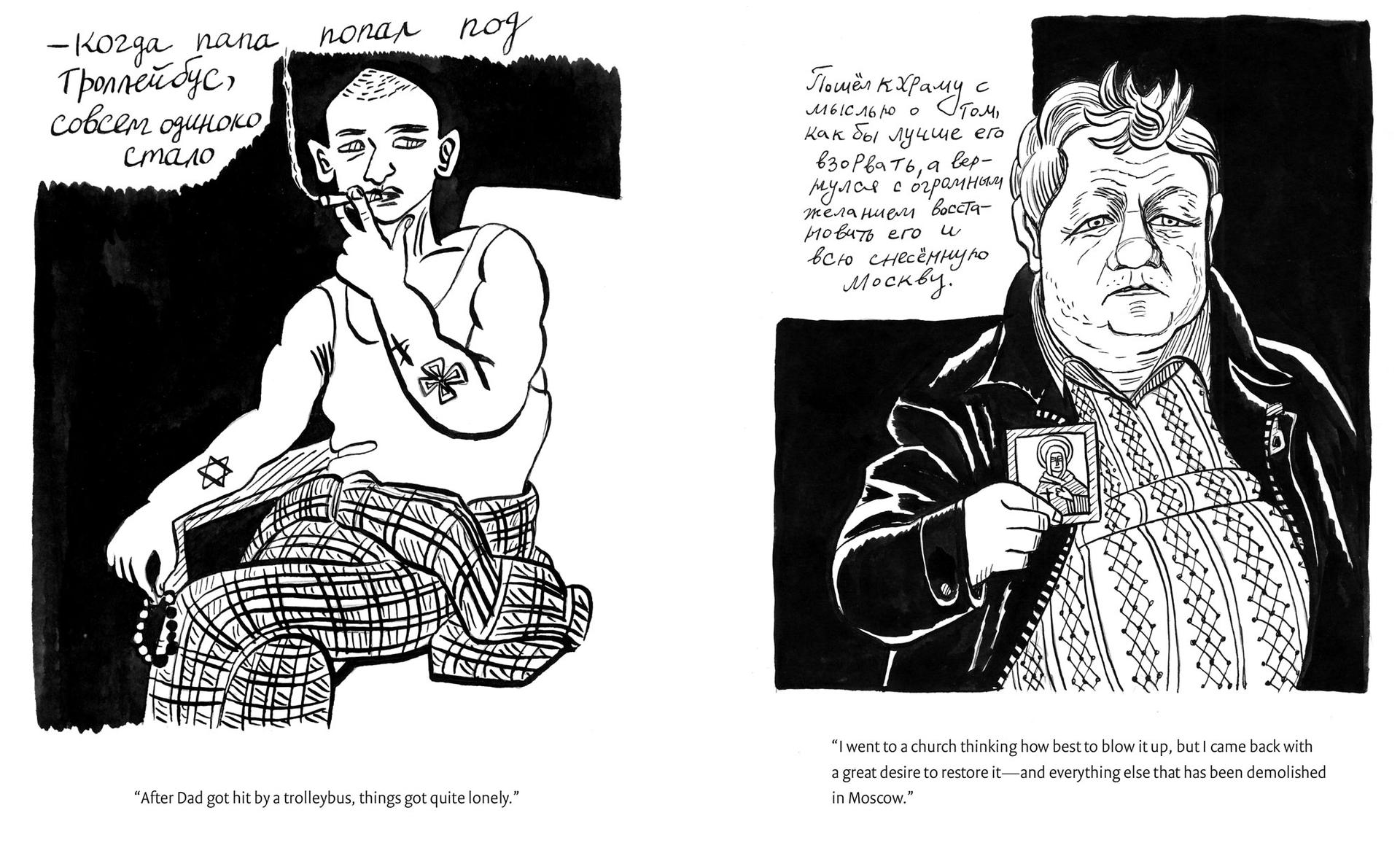

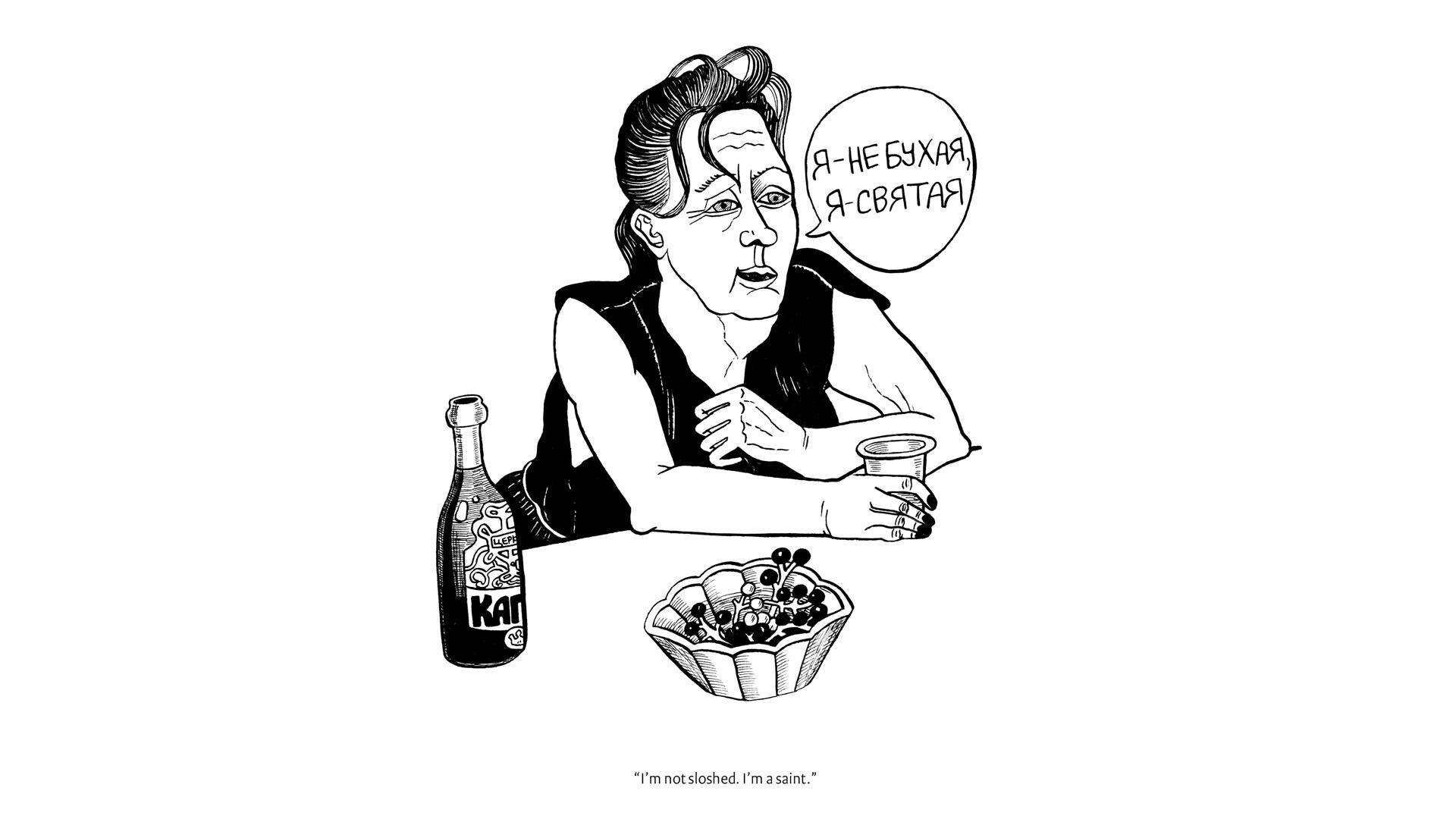

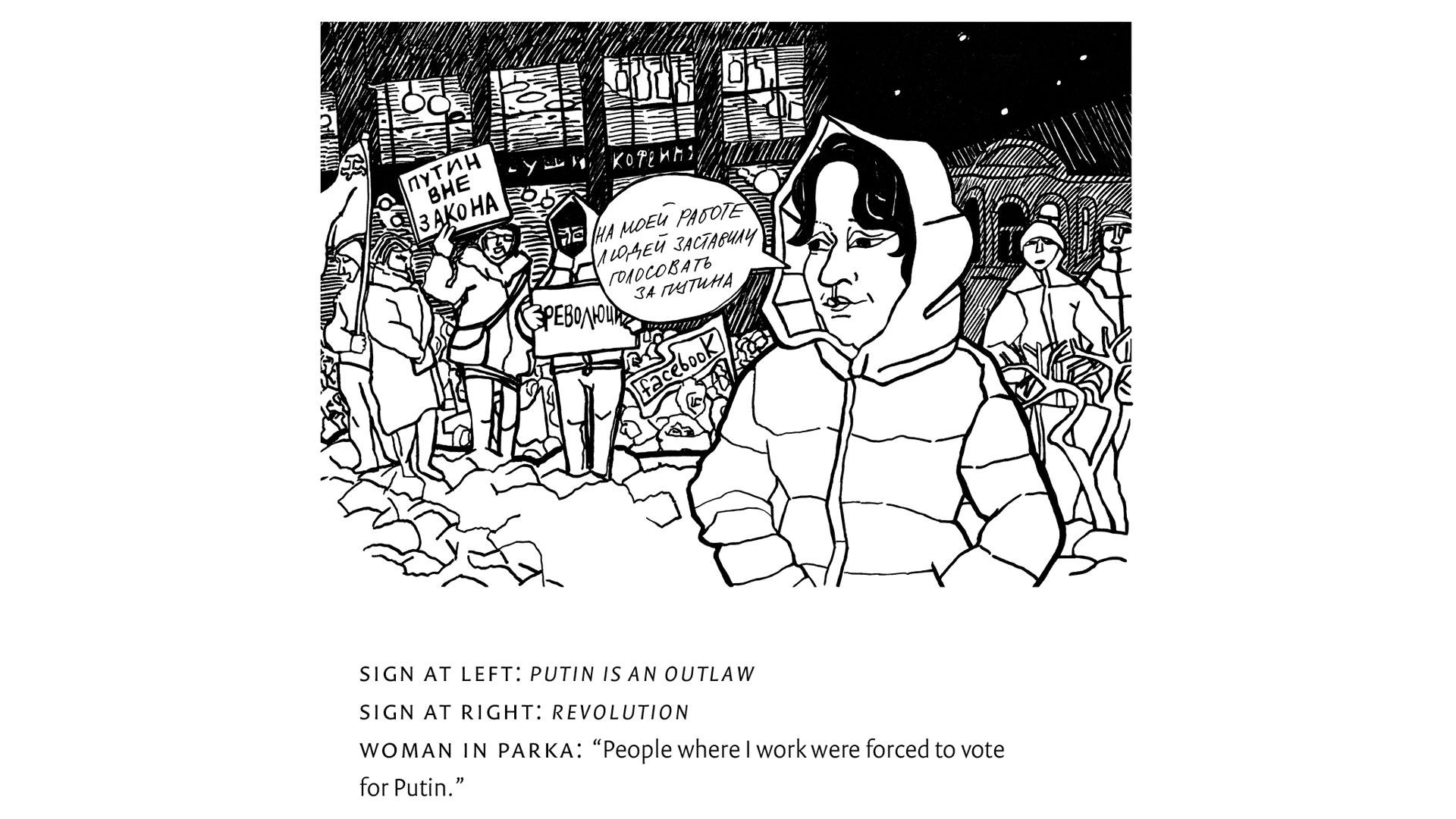

Lomasko does that by training her focus on Russia’s angry and ignored. Stark black renderings — accompanied by brief text anecdotes (and translated by Thomas Campbell) — depict a troubled nation teeming with people of stymied dreams and stunted talent.

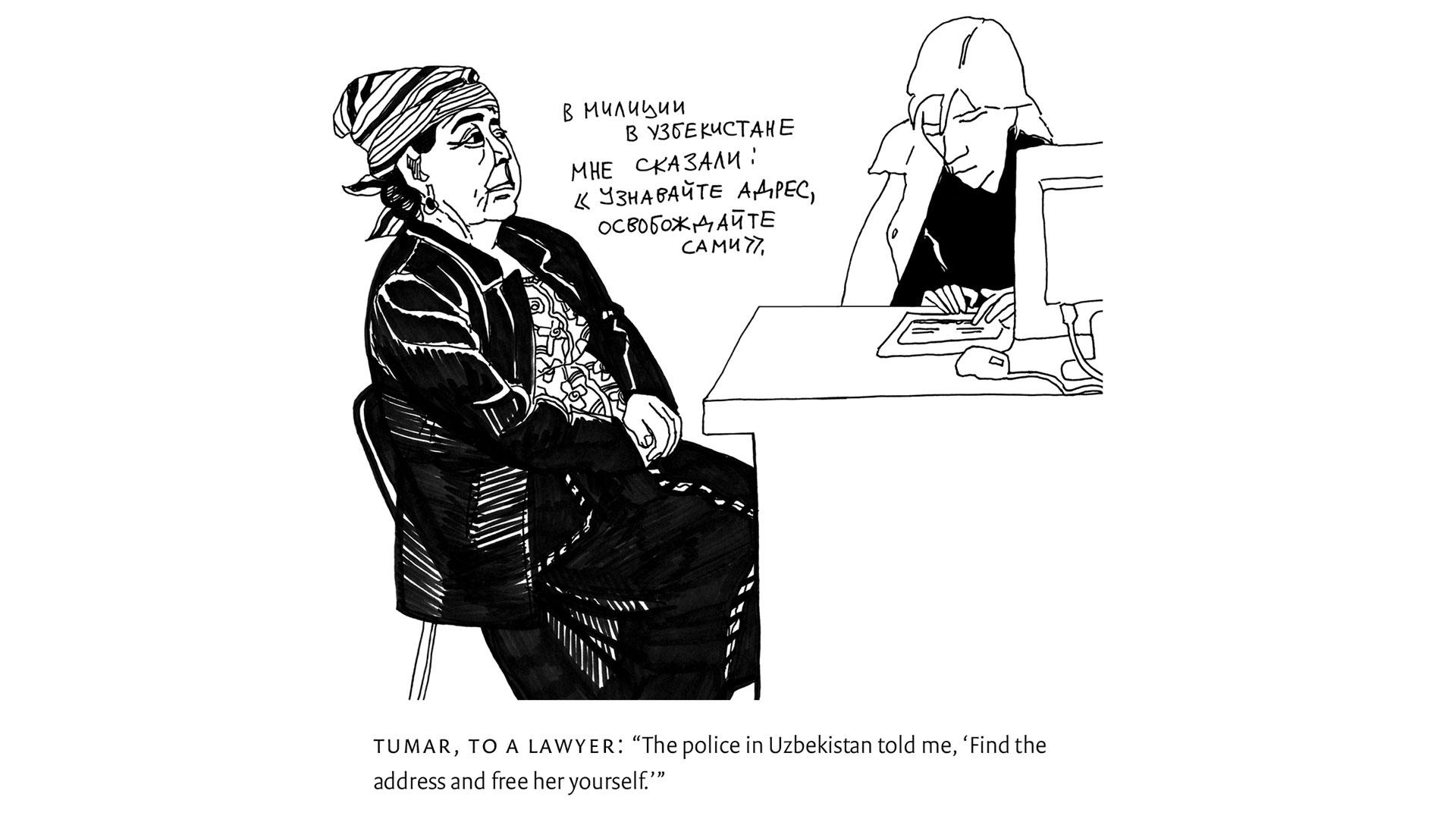

There are stories of incarcerated youth who can’t imagine a future outside of dreary prison life; Central Asian migrants seeking an out from modern-day slave conditions in the capital; and scenes of forgotten Russian village life, where locals are as unconcerned about events in Moscow as Moscow is about them.

“I’m interested in how society is built in Russia, and where I fit in,” says Lomasko. “Because there are many parts of Russian society that exist separate from one another.”

Behind that assertion lies a subtle argument: Lomasko’s outsiders, collectively, form a sort of hidden mainstream, if only they’d recognize it.

Lomasko says her subjects lend themselves to the sketchpad — not the camera — because most don’t see themselves as subjects worthy of attention at all.

“When I showed them my drawings, they said they were boring. ‘No one would be interested in us,’” recalled Lomasko. “They don’t see themselves as heroes.”

Or certainly, most do not.

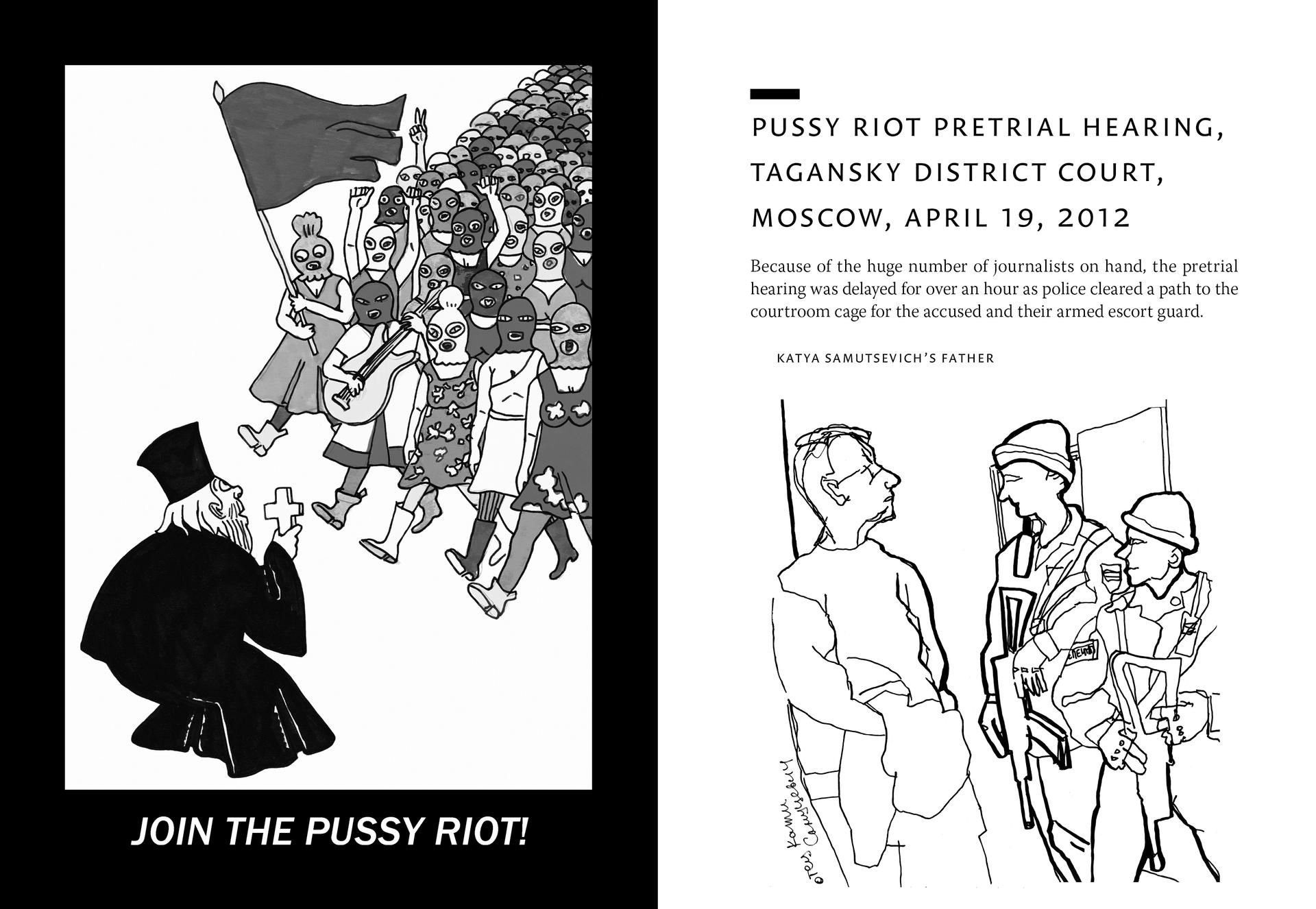

Lomasko was an early chronicler of the art-punk feminist collective Pussy Riot — capturing the tragicomedy of the group’s 2012 trial for protesting Vladimir Putin’s rule that catapulted them to prison and worldwide fame.

Yet it’s less visible women who feature most prominently in Lomasko’s drawings, with disempowerment as a major theme.

Her interest in feminist issues leads her to a sympathetic study of sex workers in the city of Nizhny Novgorod. It also prompts an examination of the lives of women in Lomasko’s own hometown of Serpukhov — a few hours outside Moscow.

There, Lomasko makes no secret of her alienation from friends who can’t understand her ambitions for a career as an artist and more.

“Russia is a traditional patriarchal country,” explains Lomasko. “Everybody expects a woman to have a husband and a child, and any other achievements don’t matter.”

“I always had this feeling that I had a voice,” she adds. “That I wasn’t just an illustrator.”

Indeed, Lomasko labels her work “graphic reportage,” as opposed to what most in the West would call it — namely, “comics journalism.”

She insists her work borrows less from the frame-by-frame narratives of the comics journalism genre and instead pays homage to home drawn historical Russian “acts of witness” — think Soviet gulag prison drawings or soldiers’ sketches from Russian wars and revolutions past.

“I don’t do classical journalism,” she says. “And maybe I miss some important facts or big global events. But I see events in a different way: not the big picture but up close. Who was next to me in the crowd? How did they feel?”

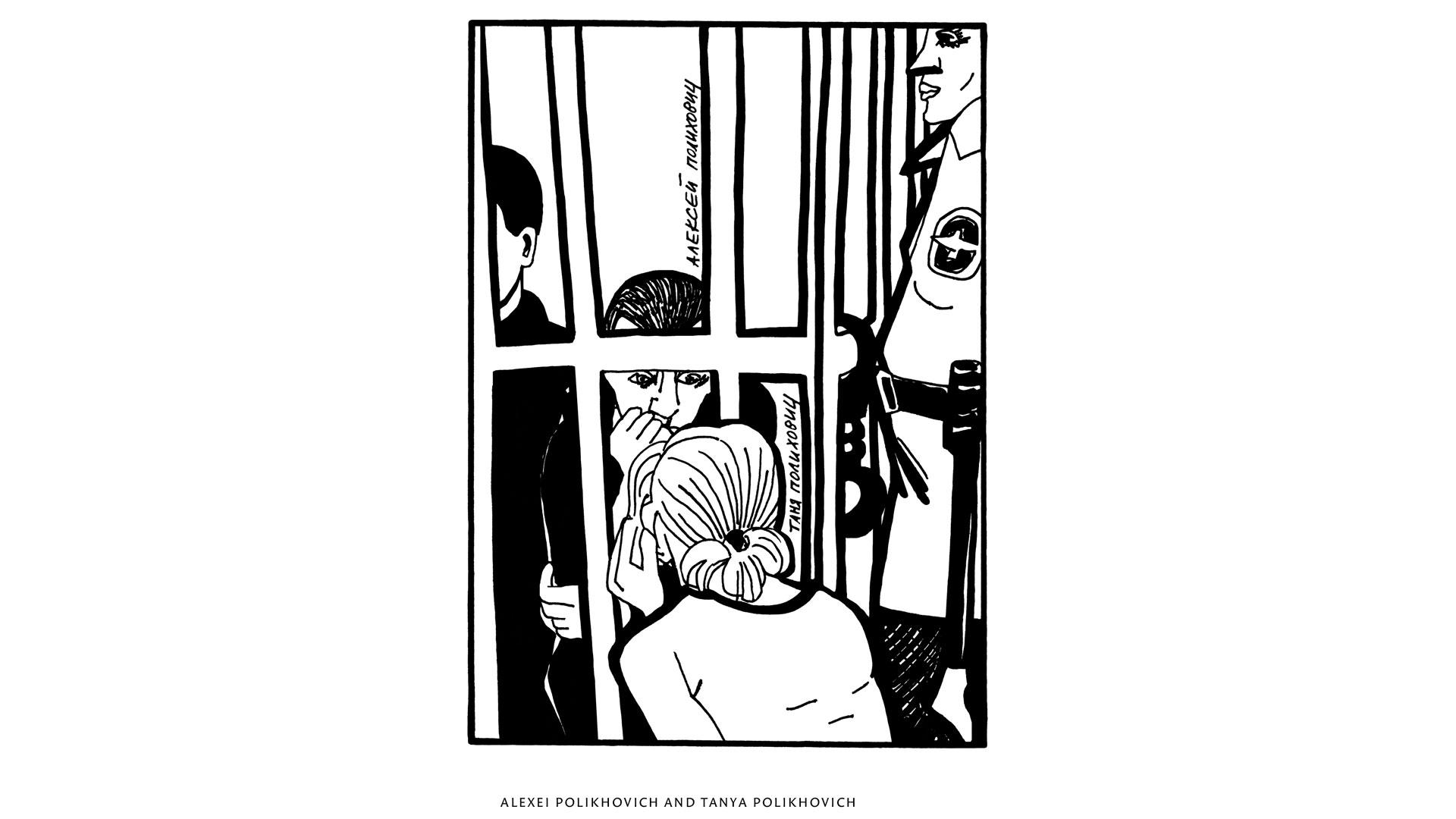

That quest takes her from a street view of Russia’s 2011 protest movement — when tens of thousands took to the streets to protest flawed elections — to witnessing the subsequent show trials that squelched the uprising and landed dozens with lengthy prison sentences.

But hope for something better never quite dies in Lomasko’s world.

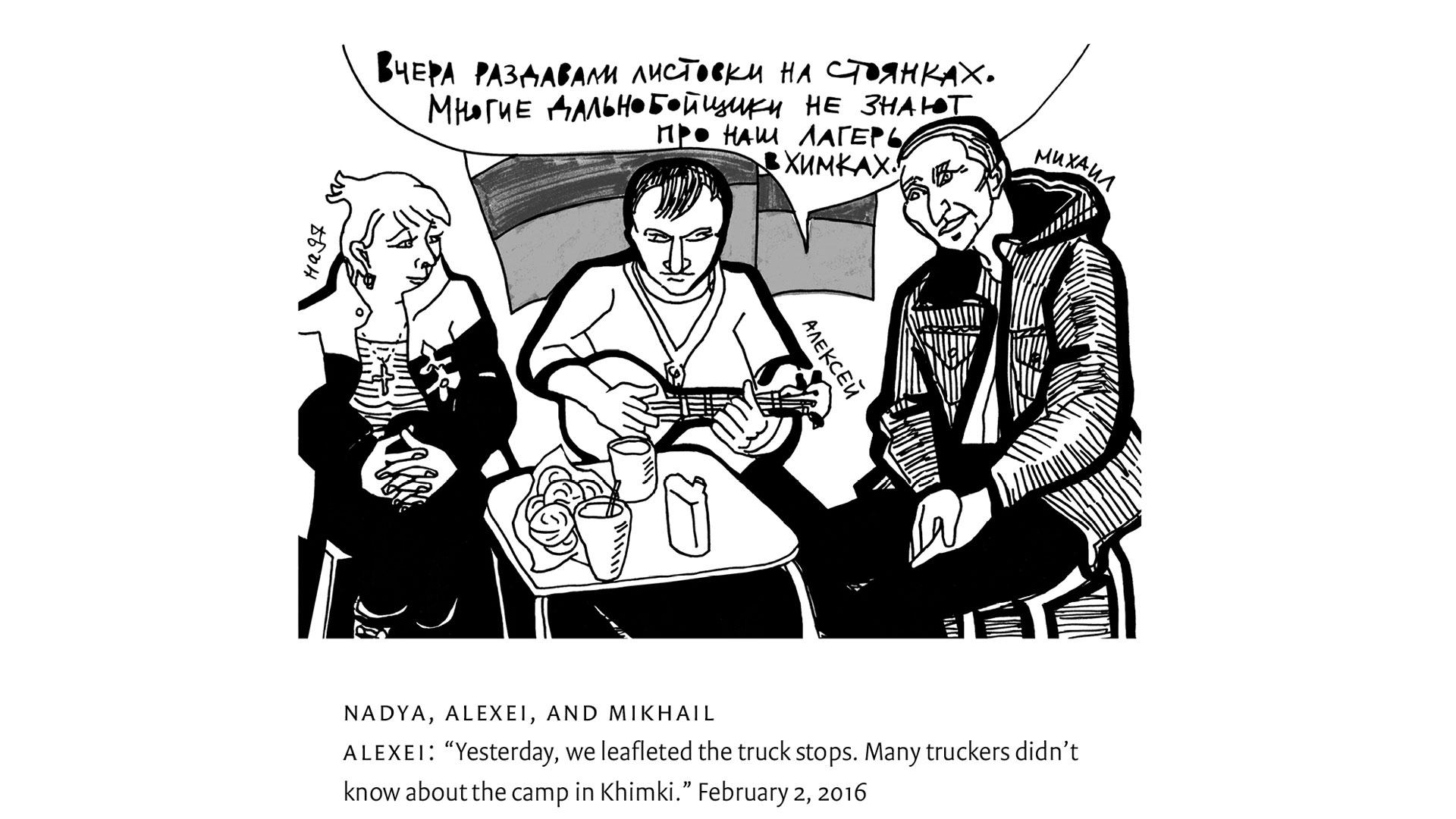

The later chapters shift her focus to Russians’ efforts to preserve the smaller things, like a suburban Moscow park from state-connected developers or a budding movement of blue-collar truckers against excessive taxes that benefit Kremlin-connected oligarchs.

And where some might suggest that reflects a shrinking of ambitions, Lomasko sees an important shift: the movement expanding beyond westernized urban intellectuals to “other Russians” — regular, working-class folks who’ve finally awakened politically to demand more.

“These park defenders and these truckers, they changed their opinions and lives completely,” she notes. “People who believed what they saw on TV and then one moment suddenly realized it was all a spell.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?