The US imprisoned Japanese Peruvians in Texas, then said they entered ‘illegally’

Japanese Peruvian men were taken to the Panama Canal Zone during World War II, photographed here on April 2, 1942, and then incarcerated in facilities in Texas and New Mexico. During World War II, the US government detained Latin Americans of Japanese descent, but left many of them without legal status to be in the US, despite releasing them into the country after the war.

Elsa Kudo was a junior in college when she learned that she was an “illegal” resident of the country she called home. Decades later, she still vividly recalled seeing her FBI file for the first time.

“What is this? Why is my file stamped ‘illegal entry’? We didn’t come illegally. You folks knew we were coming in. You brought us here,” she recalled saying in an interview with the history organization, Densho. “I was so upset.”

In the 1940s, the US government launched a program to relocate Kudo and some 2,200 other Latin Americans of Japanese descent from their home countries to detention facilities in the US.

They were taken under the pretense of a World War II prisoner exchange, but only 865 detainees were ultimately sent to Japan via the program. Several hundred others found themselves in a fight for justice that continues today.

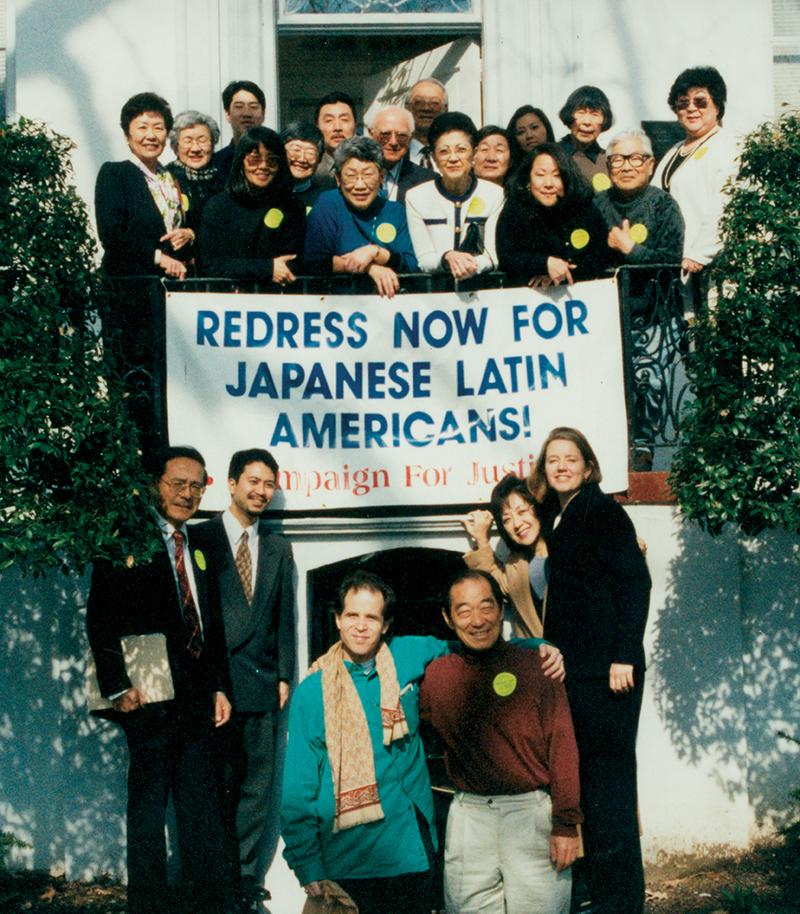

Grace Shimizu, co-founder of the Campaign for Justice: Redress Now for Japanese Latin Americans and the Japanese Peruvian Oral History Project, thinks there’s a reason Kudo and others still haven’t received adequate compensation and recognition for what happened to them.

“The US government has an interest in not redressing this kind of situation, which are basically war crimes. They want to be able to continue to kidnap people, thrust them into indefinite detention, subject them to whatever treatment,” she says, ”and not be held accountable.”

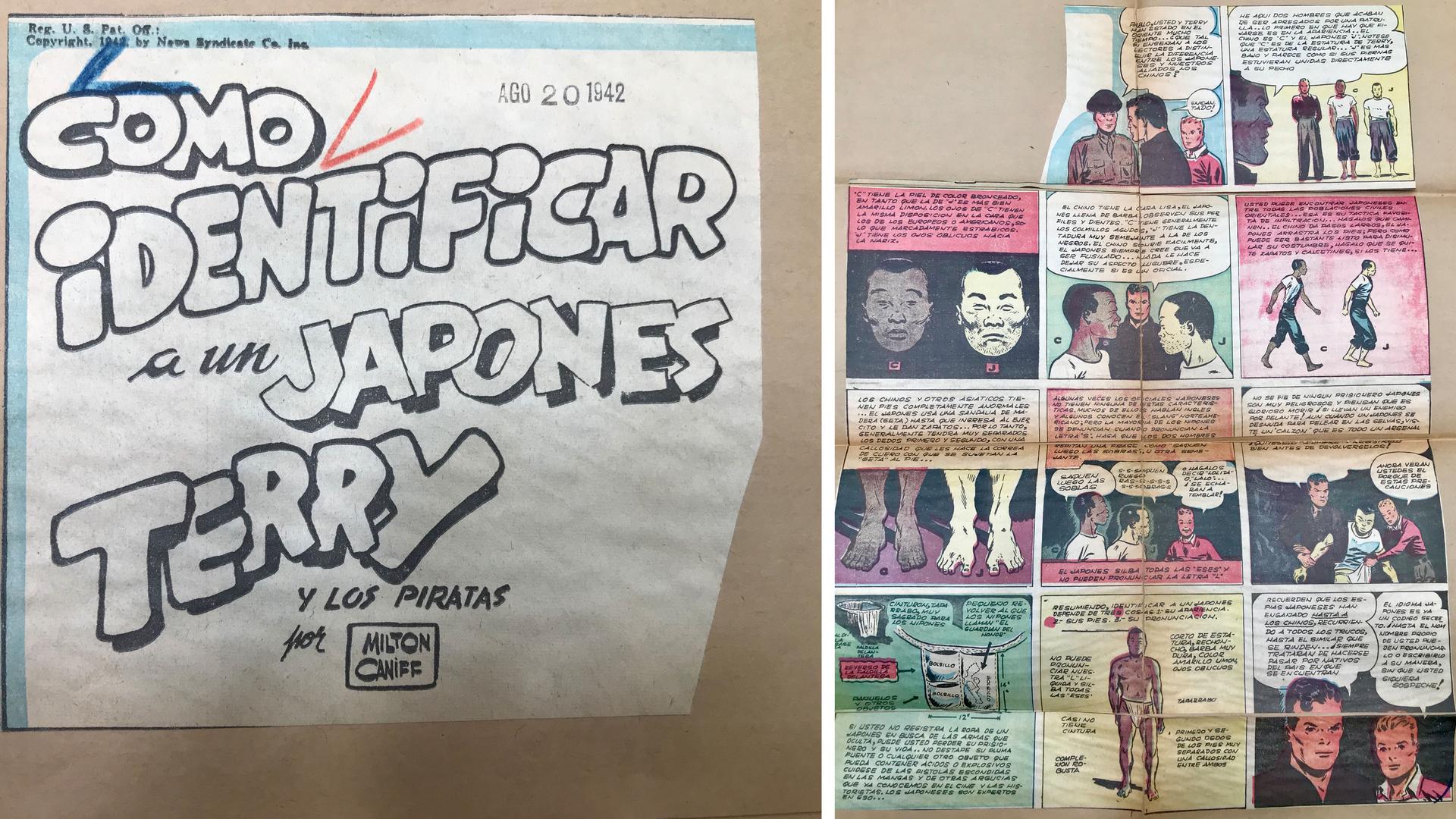

In the immediate aftermath of the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI made its first arrests of Japanese American leaders and held them in detention facilities and jails across Hawaii and the West Coast. The panic spread to Latin America too, and within 48 hours blacklists of Japanese businessmen, community leaders, teachers and others appeared in Peruvian newspapers.

The US government under president Franklin D. Roosevelt had already been surveilling Nikkei, people of Japanese descent, for years in the US and in Latin America. Central and South American presidents tried to win the favor with the US its allies by allowing FBI agents to be stationed at embassies to generate lists of those they deemed “suspect.”

Peruvian President Manuel Prado was a particularly enthusiastic accomplice; after Pearl Harbor he froze all assets held by those with Japanese citizenship and prohibited the assembly of more than three people of Japanese descent.

On Dec. 24, 1941, Seiichi Higashide, Elsa Kudo’s father, was shocked to find his name on one of those lists of “dangerous Axis nationals.” Seiichi was a Japanese immigrant in Ica, Peru, who had built a successful business, developed deep ties to his new community and started a family. He wrote in his memoir, “Adios to Tears,” that shivers coursed through his body when he saw his name. All he could think was, “Can this really be true?”

Seiichi was a wanted man but successfully avoided Peruvian authorities for two years, in part by digging a secret room into the floor of his home. In January 1944 he was caught. He was held in a jail in Lima, then at a US military-operated prison camp in Panama, and ultimately at the Crystal City detention facility in Texas for the remainder of the war. Through all of this, he had no idea where he was being taken and authorities refused to tell him why he was being punished.

The family Seiichi left behind, his wife Angelica Higashide and five children, also suffered. In a phone interview from her home in Honolulu, Kudo vividly recalled that when authorities came to take her father away, she ran down a long hallway in her family home and buried her face in a heavy, black drape.

“My tears kept coming, knowing that he was no longer with us,” she says. Years later, her mother’s friend told her, “You know, Elsita, you were such a cheerful child. After your dad was taken, I hardly ever saw you smile.”

Kudo’s mother, Angelica, was a 27-year-old child of Japanese immigrants in Peru, pregnant with her fifth child at the time of her husband’s detention. Three months after giving birth, Angelica received an urgent telegram from her husband instructing her to bring the family to Texas so they could be reunited at the detention facility. She quickly sold off the family’s shop and its inventory. She and her five children, along with her parents and sister, left their home and boarded one of the last US military ships to leave Peru with detainees and other “voluntary internees” who were following family members into captivity.

Because of the extreme stress of the situation, Angelica had difficulty nursing her newborn, so she stocked up on canned milk to feed her infant for the duration of the journey. However, the milk was confiscated before they boarded the ship. She tried to nurse again, but could produce only blood.

Kudo remembered that her mother begged an American soldier for help.

”She didn’t know English, so she would plead in Spanish, ‘Please, milk for my baby,’ and he would pretend not to understand. I mean, how stupid can you be? You know what I mean? It’s just very prejudicial.”

Finally, Angelica found a Filipino soldier who understood her request and took pity on her. He supplied her with milk during the journey.

The family was eventually reunited at the Crystal City detention facility, just an hour east of the South Texas Detention Complex where nearly 2,000 migrants and asylum seekers are being held today. Crystal City was operated by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the precursor to the agencies in the Department of Homeland Security that control immigration and detention today. The center primarily held families of Japanese descent from Latin America, as well as a smaller number of German and Italian families.

Immigration from Japan spiked throughout Latin America after the US prohibited Japanese immigration in 1924. But in 1936, Peru issued its own ban that, according to historian Benjamin DuMontier, reflected widespread stigmatization of Japanese immigrants as “bestial,” “untrustworthy,” “militaristic” and “unfairly” competing with Peruvians for wages.

As DuMontier wrote in his 2018 dissertation for the University of Arizona, pre-war anti-Japanese fervor reached a climax in a three-day race riot targeting Japanese Peruvian individuals, homes and businesses in May 1940. The “Saqueo,” as it’s known, resulted in approximately $1.6 million in damage and is still considered one of the most traumatic events in Japanese Peruvian history.

Tensions simmered as Peruvian authorities continued to debate how to deal with what was commonly referred to as the “Japanese problem.” Pearl Harbor and US-led “national security” measures presented a lucrative solution. Though not a direct exchange for detainees, the US government lent Peru $29 million during World War II and provided military support and ships.

The paper trail indicates that President Manuel Prado was also motivated by the desire to rid Peru of all its Japanese-descended citizens and residents — which some historians have argued amounted to a campaign of ethnic cleansing. In a letter documenting a visit Prado made to the US, US ambassador to Peru Raymond Henry Norweb wrote:

“In any arrangement that might be made for internment of Japanese in the States, Peru would like to be sure that these Japanese would not be returned to Peru later on. The President’s goal apparently is the substantial elimination of the Japanese colony in Peru.”

Though men were the primary targets of this extraordinary rendition, their families often opted to follow them out of economic necessity, fears for safety or concern that they might not be reunited otherwise. Seiichi wrote in his memoir that some families who chose to stay behind found themselves in the “unbearably sad circumstances” of going decades without seeing their loved ones.

Once the Higashides were finally reunited in the US, they were imprisoned alongside other “enemy aliens” and their families at the Crystal City detention facility.

They lived in rustic barracks with no insulation. During the summer months temperatures outside reached upwards of 120 degrees and Seiichi recalls the barracks becoming a “hellish oven” with metal bed frames so hot you couldn’t touch them without blistering.

The Higashide family’s troubles didn’t end when the war did. Instead, they and hundreds of other Japanese Latin Americans found themselves in a stateless, legal limbo.

In September 1945, US President Harry Truman issued a proclamation authorizing the removal of all “enemy aliens” from US soil. Peru only allowed those with Peruvian citizenship to return. Though none were found guilty of espionage or any other crimes, newspaper headlines characterized those who returned as “leaders of the Japanese fifth column.” In all, only 80 Japanese Peruvians returned to the country that had been their home. Another 900 relocated to wartorn Japan, where many had to restart their lives in a land and speaking a language that was foreign to them.

The Higashides and several hundred other Japanese Latin Americans were able to stay in the US thanks to legal action taken by civil rights attorneys Wayne M. Collins and A.L. Wirin. The lawyers won a court order blocking the removal of 364 Japanese Peruvians, then secured temporary permission for them to remain as laborers at Seabrook Farms, a major producer of frozen and canned foods in New Jersey. But they were still undocumented and considered “illegal aliens” in their government paperwork.

More about the workers at Seabrook Farms: A lesson from history about protecting migrant workers

In September 1946, the Higashide family relocated to Seabrook Farms to work alongside hundreds of other displaced Nikkei from the US and Latin America. “The transfer to this place from our former life behind barbed-wire fences was no more than a shift from complete confinement to partial confinement,” Seiichi wrote.

They were provided housing, but remembered it being worse than the barracks they lived in at Crystal City. Low wages were taxed heavily and workers had little choice but to buy food at inflated prices from the company store. The Higashides’ youngest son, Richard, was born at Seabrook. The family was so poor — and so resourceful — that Angelica made clothing out of the baby’s cloth diapers once he outgrew them.

The Higashides stayed at Seabrook for two years before eventually relocating to Chicago. For several years, the family of eight lived in extreme poverty, with Angelica working factory jobs and Seiichi taking whatever work he could find. Chicago’s restrictive housing laws made renting a large enough home nearly impossible, so the family eventually secured loans and purchased properties they could live in and rent out to others.

Kudo did enough babysitting to eventually put herself through college at the University of Illinois at Chicago. But it was there that she fully realized the precarity of her “illegal” residence in the US.

Other Japanese Latin Americans were also realizing that their wartime ordeal was far from over. Like Kudo, Isamu Carlos Arturo “Art” Shibayama was relocated from Peru to Crystal City in his youth. He also lived at Seabrook Farms with his family after the war and was similarly deemed “illegal” by the US government.

Even so, he was drafted to the US Army in 1952 and required to serve the country that had conspired to abduct and imprison his family, then denied them citizenship. While stationed in Germany, Shibayama’s superior officer applied for US citizenship on his behalf, but the US government declared him ineligible, claiming he had entered the United States illegally.

Provisions made in the Immigration Act of 1952 allowed Japanese Latin Americans, and others who had been banned by racially exclusionary immigration laws, to become eligible for citizenship. But Shibayama and others’ paths were still complicated because the US still said they entered the country illegally. Some Japanese Latin Americans became US citizens in the 1950s, but Shibayama didn’t receive his citizenship until 1972.

By the 1970s, Kudo relocated to Hawaii with her husband and started a family there. Her parents and several siblings eventually followed. Life finally became easier for Kudo’s family, but a new struggle was just beginning.

As Japanese Americans fought for redress over the course of the 1970s and ’80s, Seiichi, Shibayama and other Japanese Latin Americans fought alongside them. Japanese Americans finally won an official presidential apology and individual payments of $20,000 in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 — redress Japanese Latin Americans later learned they didn’t qualify for because of their “illegal” entry into the country.

Shibayama, Kudo, Seiichi and Shimizu joined the Campaign for Justice. The group filed a class-action lawsuit in 1996, Carmen Mochizuki et. al. v the United States, that resulted in an out-of-court settlement that promised $5,000 to each of the Japanese Latin American survivors. Shibayama called the lower individual payments and the generic apology letter included with the checks “a slap in the face.”

Some, including Shibayama, refused to accept the settlement. Other Japanese Latin Americans never received checks because the Office of Redress Administration ran out of funds after paying only 145 claimants, leaving more than 500 eligible claimants empty-handed.

Shibayama and his two brothers filed five additional lawsuits and helped craft two pieces of redress legislation, none of which were successful. In 2003, the Shibayama brothers filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, arguing that crimes had occurred under the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, to which the US was a signatory in 1948. Their case was finally heard in Washington, DC, 14 years later, in March 2017, but the Trump administration refused to participate in the hearings.

After learning about the plight of Japanese Latin Americans, the commission offered personal apologies and agreed to investigate, but a ruling is still outstanding and there is no clear timeline for when it will be decided. Shibayama died in July 2018 at age 88.

The Peruvian government has not formally redressed its World War II actions either. But President Fernando Belaúnde Terry did provide Japanese Peruvians with a parcel of valuable land in the middle of Lima in the 1960s. The space is now home to the Centro Cultural Peruano Japonés and has become a major hub for Lima’s Japanese Peruvian community.

“The land wasn’t explicitly given to redress the World War II actions of the Peruvian government, but there’s a sort of tacit understanding that that’s what it was for,” historian DuMontier says.

President Alan García apologized to members of the Japanese Peruvian Association there in 2011, just before he left office.

Shimizu continues to lead the fight for justice in the US. Born in 1950s Berkeley, California, her father was a Japanese Peruvian businessman, who, like Seiichi Higashide, was blacklisted and forcibly relocated to the US. Since the early 1990s, Shimizu has worked to document and expose this little-known US program of extraordinary rendition, and to secure redress for those victimized by it. She also sees many connections between her family’s history and the constitutional and humanitarian challenges of today.

“Redress isn’t finished. It’s a human rights issue, and this unfinished World War II business is important to all,” Shimuzu says.

This story was corrected to include the correct date in which the government of Peru gave land to Japanese Peruvians, and to include information about the apology offerred by President Alan García.

The story was produced in partnership with Densho, a nonprofit organization that preserves the histories of Japanese Americans.