Is Pakistan poised for a Pashtun Spring?

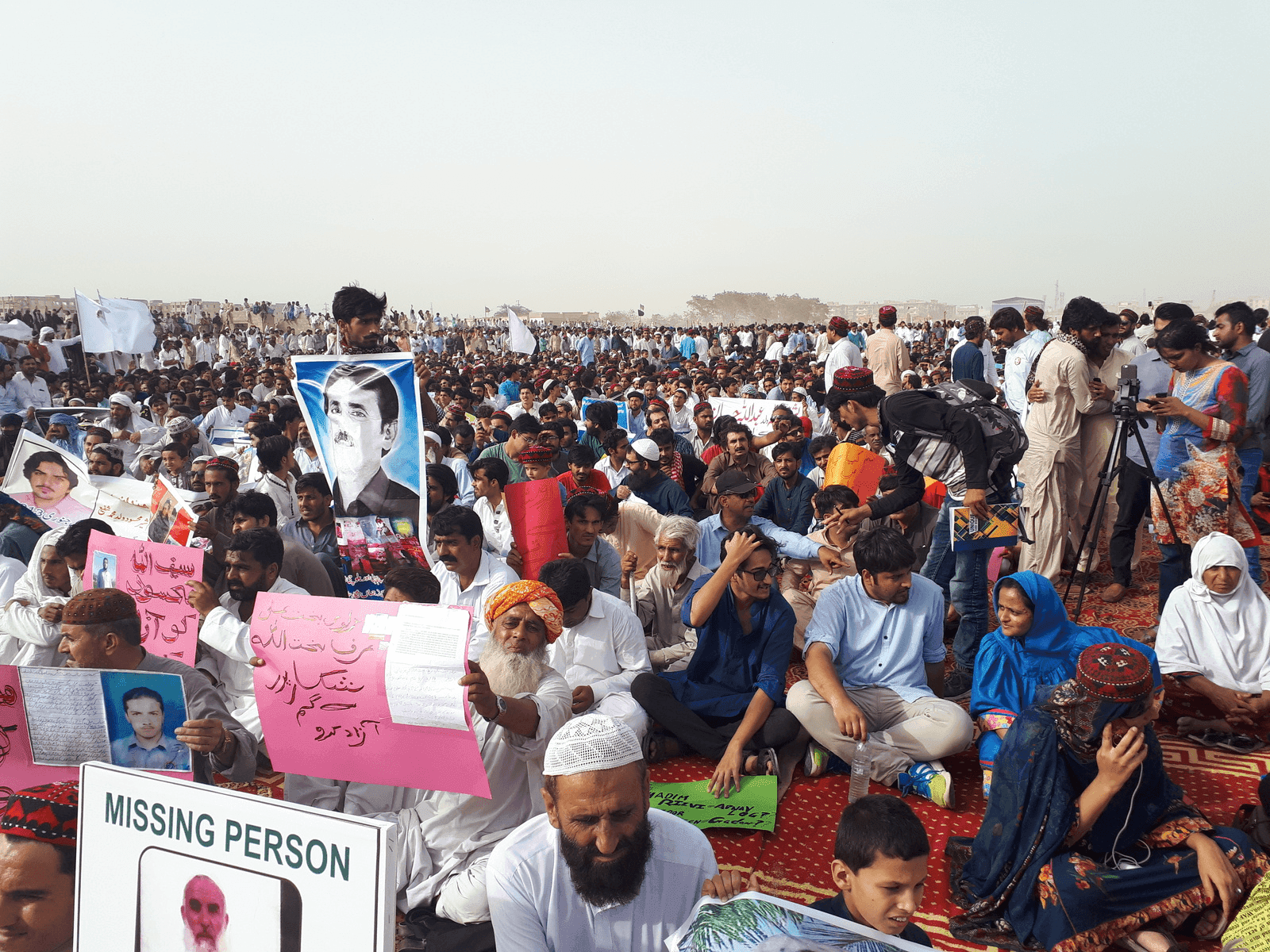

Hameeda Baloch, whose brother Sagheer Ahmed Baloch disappeared from the University of Karachi in 2017, holds his photograph at the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement rally on May 13, 2018 in the southern Pakistan city of Karachi.

Every time someone knocks on the door, Mishal Sher jumps, thinking her father might have finally returned home.

It’s never been the case since he vanished four years ago.

She says she knows how he disappeared, just not why.

“Some unidentified men barged into our house and took away my father,” said Sher, 16, recalling how her father Sher Khan, a Pashtun from the tribal area of Mohmand District in northwest Pakistan, disappeared in October 2014 from Lahore where he had gone to find work. “My father used to drive an auto rickshaw to make ends meet. We don’t know what his crime was, who took him and where he is now.”

Many others also mourn the thousands of missing Pashtuns in Pakistan.

Pashtuns are an ethnic minority group of about 49 million people, the biggest share of them in Pakistan. They often live in remote areas, like Waziristan in the west, that have become battlegrounds between Pakistani troops and Taliban militants — many of whom are also ethnic Pashtuns. Security forces have cracked down on their communities as a result, and over the past decade thousands of people have disappeared without a trace. There are no concrete numbers available, but estimates from Pashtun organizations estimate as many as 30,000 people have disappeared; Pakistani human rights organizations cite around 5,000.

“The term ‘missing persons’ reflects the pain and misery of families — and there are not a few families but thousands of them living each day in search of something they might never find,” said Manzoor Pashteen, 26, a veterinarian and who founded the Pashtun rights group Mehsud Tahafuz Movement in 2013. “When you see the dead body you get closure, but when you just see ‘missing person’ it increases the ordeal.”

In May, Pakistani lawmakers passed a new law that will incorporate Waziristan and other areas into a neighboring province and inject $850 million a year into the region for a decade to establish courts, government offices and boost economic development.

The measures are an attempt to defuse widespread anger over how the central government in Islamabad has treated the region — locals say they have either been ignored, neglected or abused. But for families with disappeared loved ones, the new measures are empty gestures.

That’s because for years the loved ones of the disappeared have desperately wondered if they would ever learn where their friend or family member is or what happened to them. Authorities refuse to answer inquiries; most say they have hit a brick wall.

But over the past six months, a rising movement for equal rights and protections for the Pashtun minority is giving these people hope for answers.

“It is because of this movement that I am hopeful that my father might actually come back, or at least I could see him again,” said Sher.

It started in January after police apprehended Naqeebullah Mehsud, 27, in the southern Pakistani city of Karachi. Authorities suspected Mehsud was a Taliban militant. A few weeks later, Mehsud died in a firefight with police. Meshud’s family and friends, however, said he was a shopkeeper and aspiring model who had no links to terror.

Meshud’s death contributed to the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement’s call for an end to extrajudicial killings, forcible disappearances, racial profiling, landmine removal and the state treating them like second-class citizens.

The movement has seen thousands hit the streets in cities such as Karachi, Islamabad and Peshawar since January. Pashtun mothers, fathers, wives, children and siblings hold placards with photos and details of missing loved ones they believe are imprisoned or dead.

Awais Haider, whose brother Ejaz went missing in June 2011 in the northwestern city of Mardan, regualarly attends the protests.

“The case against my brother’s disappearance is ongoing since 2012, but he hasn’t been produced in the court even once,” said Haider. “I appeal to the chief justice and the army chief to bring my brother in the court. This is our constitutional right.”

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan has long been concerned over the state of enforced disappearances in the country.

“The fact that enforced disappearances have continued unabated in the last years is cause for serious concern and unacceptable,” commission chairman Mehdi Hasan said recently, calling on Pakistan to sign the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances.

In a statement on March 19, Amnesty International urged Pakistan to resolve hundreds of cases of enforced disappearances: “No one has ever been held accountable for an enforced disappearance in Pakistan,” the watchdog organization said. “The disappeared are at risk of torture and even death. If they are released, the physical and psychological scars endure. If they are killed, the family never recovers from their loss. Disappearances are a tool of terror that strikes not just individuals or families, but entire societies.”

Meanwhile, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has more than 700 pending cases from Pakistan.

The government-run Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearance claims to have investigated almost 5,000 missing persons.

The chairman of the commission, Javed Iqbal, told lawmakers that more than 4,000 Pakistanis were secretly handed over to foreign countries in return for money under former military ruler Pervez Musharraf’s regime.

“For how much did they sell 4,000 missing persons?” Pashteen asked. “We should be told the amount so that we can collect that money and bring them back and bring them to the court if they are criminals.”

While the Pashtun movement has grown stronger, it has also rattled the strong military establishment in Pakistan, which Pashtuns like Pashteen say have imposed a media blackout on coverage of the protests.

In June, police arrested 37 Pashtun protesters on “sedition charges” for chanting “anti-state” slogans.

Meanwhile, Army Chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa has questioned whether the protests are real or “engineered.”

Counter-protesters have heckled Pashtun leaders, calling them “anti-state” foreign agents. Such sentiments provoke ironic laughter from the families of the disappeared.

“If we as ‘agents’ are asking for peace and constitutional rights, then what are the ISI agents doing?” Pashteen asked, referring to the country’s intelligence service, the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence agency.

Pashteen might have a point. His demand for Pashtun justice has resonated with other repressed ethnic groups in Pakistan, like the Baloch community whose members speak an Iranian-like language.

“I only say that if my brother is guilty of breaking any law he should be brought to the court,” said Hameeda Baloch, 16, whose brother Sagheer Ahmed Baloch disappeared.

Baloch, 21, a political science student at the University of Karachi, disappeared from the campus last November. His sister says Baloch’s only crime is that he hails from Awaran, a restive district in Balochistan, in the country’s southwest.

“I don’t want my brother Sagheer’s mutilated body [returned to me] like many other missing persons end up,” she said. “I need justice. My brother is only a student. His abduction is a crime according to international law.”

Still, Pashtuns are hoping that recent elections might give their movement more power.

With cricketer-cum-politician Imran Khan — an outsider from the dynasties that usually control Pakistan — ready to take the reins as prime minister this month, the families are hoping they might finally get answers.

Khan has called the demands of Manzoor Pashteen “genuine.” He has also promised that he will meet the army chief to discuss easing security checks and removing landmines, as well as the “core issue of missing persons of the tribal areas.”

Also, two of the Pashtun movement’s leaders, Ali Wazir and Mohsin Dawar, won seats from tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as independent candidates.

Meanwhile, Murad Khan continues to wait for news of his son. Ataullah, 15, was working at the Liaquat National Hospital in Karachi when men — no one is certain who — picked him up in February 2015.

“Three years have passed and there is no news about my son,” he said. “No one knows where he is.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?