Honoring Annan, McCain and others: Why eulogies have blind spots

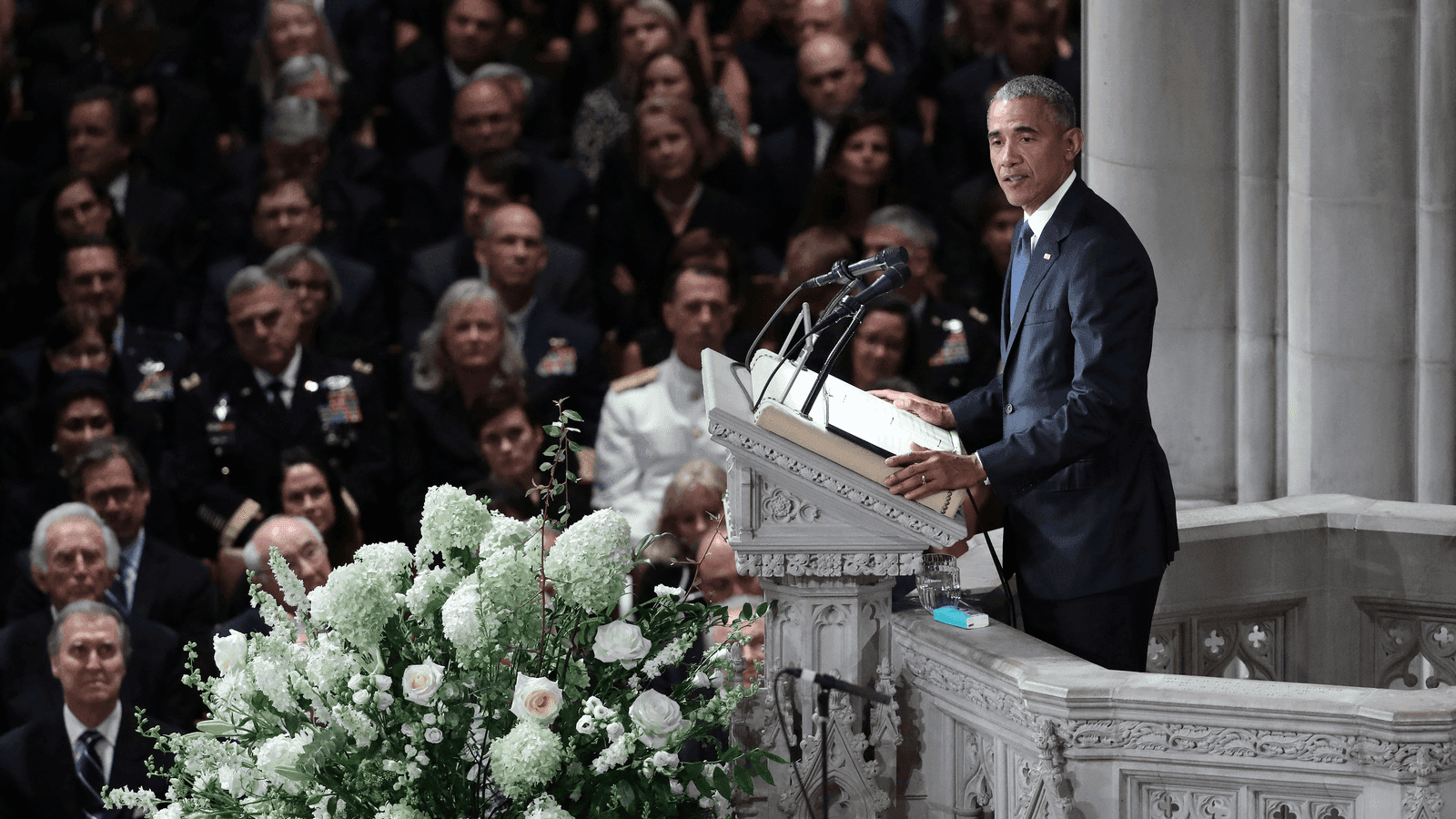

Former US President Barack Obama speaks at the memorial service of US Senator John McCain at National Cathedral in Washington, DC, Sept. 1, 2018.

As an old adage says: “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” So it should not come as a surprise that prominent people are sometimes remembered selectively when they are dead.

Perspectives have blind spots. We often appreciate or dislike others because of how we relate to them through our spectacles, colored by the values we treasure. There is a wide zone between fact and fiction. The truth is that the interpretation of others’ legacies often reveals a great deal about us and our values. And is often less about the complexity of the lives of those with whom we engage.

I have experienced such a balancing act in my engagements with Dag Hammarskjöld, the second secretary-general of the United Nations, before he met his untimely death in a plane crash at Ndola, in then Northern Rhodesia (today Zambia), in 1961.

As the world’s highest international civil servant, Hammarskjöld provoked divided opinions. Some saw him as a tool of Western imperialism for the assassination of the Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba; others praised him as being close to a saint.

Kofi Annan, the UN secretary-general who recently passed away, said that Hammarskjöld was his role model. The obituaries that followed Annan’s death led me to reflect on the two men, the legacies they left, and how imperfectly high-profile people are remembered after they’re gone.

Politicians and diplomats are a special breed. We owe it to them and to us, to find an adequate way of engaging with their legacies in a format that avoids the superficial praise song and highlights the contradictions when entering the power games of policy.

Kofi Annan

There wasn’t much of a balancing act when it came to remembering Annan. Many eulogies had few critical undertones for “a man who cared for humanity.”

Some managed to address his complicated legacy while others were courageous enough to emphasize his shortcomings as secretary-general, including his refusal “to acknowledge any meaningful sense of personal or institutional responsibility” for some major debacles.

Related: Former UN leader Kofi Annan dies in Switzerland

But these remained the odd ones out. Others were quick to list his merits, which outweighed the shortcomings as a man who paid his dues.

Many obituaries conceded the impact of his influence on the global stage. But acknowledgments missed mentioning at least two other Africans, who during Annan’s terms played an important role in the agenda-setting he is praised for. Lakhdar Brahimi was crucial in promoting more effective peacekeeping operations; Francis Deng made major contributions towards the UN’s “Responsibility to Protect” agenda.

Like others — think of former-US President Jimmy Carter’s track record as human rights advocate and his modest lifestyle — Annan’s merits lie more in his time after office. Most prominently in his role as one of the Elders.

He was a noteworthy mediator, most spectacularly in Kenya. Commendable is also his recent commitment towards a solution for the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar.

What might explain the overtly positive eulogies to Annan is that there were moments of human dignity and decency, in which the opportunity was seized to set a morally acceptable example. This seems to have also been the case when it comes to John McCain, American politician and military officer who recently passed on.

John McCain

McCain was widely celebrated in the established media as war hero and maverick. He was also deemed an American hero, whose “principles and belief in bi-partisanship” made him unique.

Related: John McCain, ex-POW and ‘maverick Republican,’ dies at 81

But moments of personal integrity were at times deeply ambiguous. His defending Barack Obama as “a decent man” and “family father” was far from dismissing racism. It only exonerated his contender and should not make up for McCain being willing to compromise his declared principles in his bid for presidential power.

The conservative values praised as a sign of integrity, elevating him into “a class of his own” should not distract from McCain’s role as a warmonger who did not care for human life and dignity.

Weigh right and wrong

All too often — and Annan has been a particularly prominent example — those praising a person highlight their own involvement. They cannot resist focusing on the impact the person had on them or when and where the person left a lasting impression through a personal encounter. Often, such eulogies reproduce a photo of the praised person, shown together with the one who applauds her or his merits — almost as if these were their own merits.

This leaves me wondering what kind of memory will be paid to Obama. As the first black president of the US, there were a number of things deserving positive recognition, mainly in domestic policy. But they should not prevent a condemnation of his massive failures. But then, in the shadow of Obama’s through-and-through immoral successor in office, it already makes a difference to display some degree of ethics, moral consciousness and decency.

Maybe this is also a valid explanation why so many failed in their tributes to Annan or McCain. It might be difficult to enter the necessary investigations of what is right and what is wrong in times when reactionary populism requires a desperate search for alternatives. But, it is in support of such alternatives that we shouldn’t shy away from the challenge.

Henning Melber is an extraordinary professor in the department of political sciences at the University of Pretoria.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()