From laboratory in far west, China’s surveillance state spreads quietly

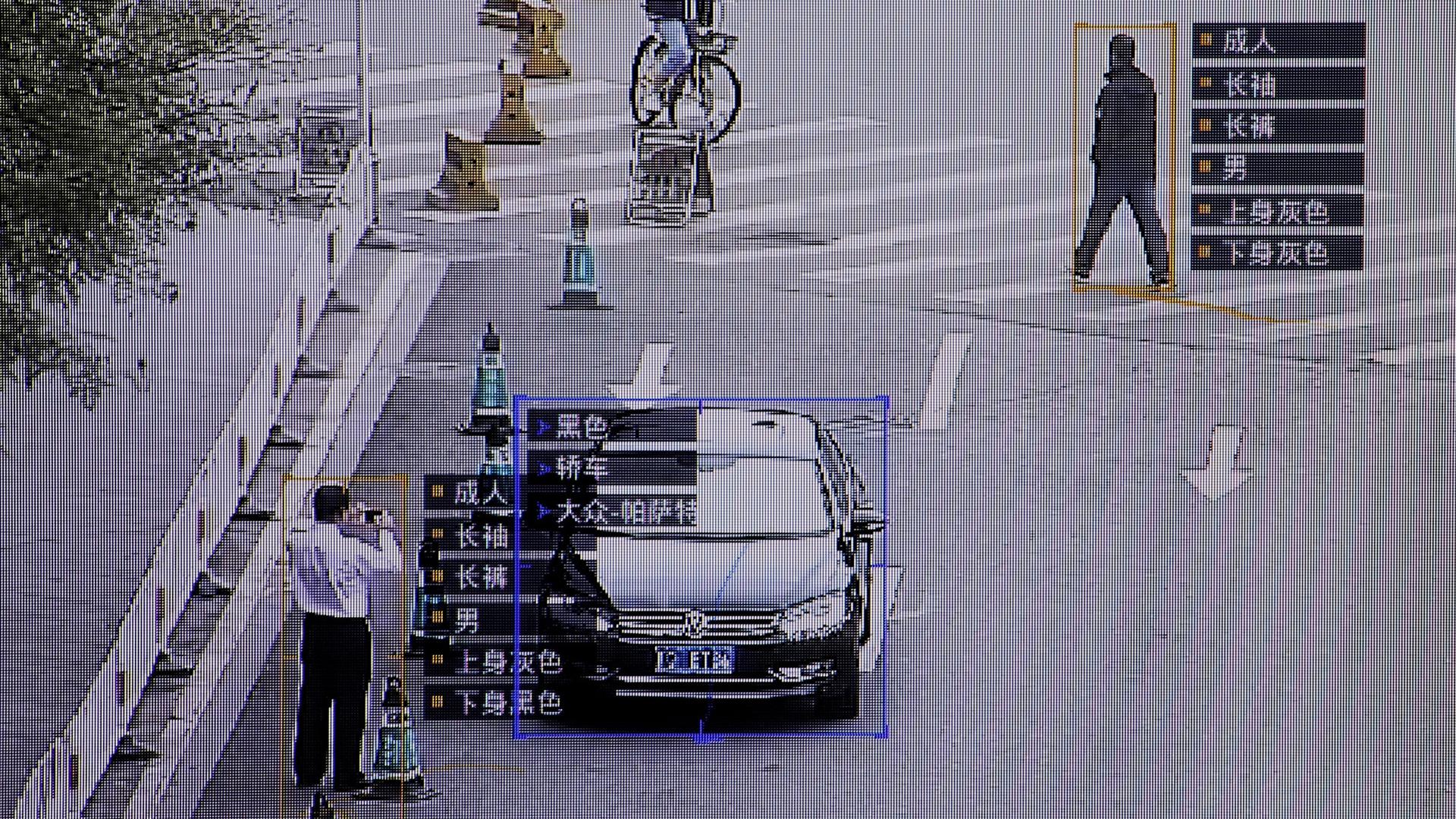

SenseTime surveillance software identifying details about people and vehicles runs as a demonstration at the company’s office in Beijing, China.

Filip Liu, a 31-year-old software developer from Beijing, was traveling in the far western Chinese region of Xinjiang when he was pulled to one side by police as he got off a bus.

The officers took Liu’s iPhone, hooked it up to a handheld device that looked like a laptop and told him they were “checking his phone for illegal information.”

Liu’s experience in Urumqi, the Xinjiang capital, is not uncommon in a region that has been wracked by separatist violence and a crackdown by security forces.

But such surveillance technologies, tested out in the laboratory of Xinjiang, are now quietly spreading across China.

Government procurement documents collected by Reuters and rare insights from officials show the technology Liu encountered in Xinjiang is encroaching into cities like Shanghai and Beijing.

Police stations in almost every province have sought to buy the data-extraction devices for smartphones since the beginning of 2016, coinciding with a sharp rise in spending on internal security and a crackdown on dissent, the data show.

The documents provide a rare glimpse into the numbers behind China’s push to arm security forces with high-tech monitoring tools as the government clamps down on dissent.

The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the Public Security Bureau, which oversee China’s high-tech security projects, did not respond to requests for comment.

The scanners are hand-held or desktop devices that can break into smartphones and extract and analyze contact lists, photos, videos, social media posts and email.

Hand-held devices allow police to quickly check the content of phones on the street. Liu, the Beijing software developer, said the police were able to review his data on the spot. They apparently didn’t find anything objectionable as he was not detained.

The data Reuters analyzed includes requests from 171 police stations across 32 out of 33 official mainland provinces, regions and municipalities, and appears to show only a portion of total spending.

The data shows over 129 million yuan ($19 million) in budgeting or spending on the equipment since the beginning of 2016, with amounts accelerating in 2017 and 2018.

In Shanghai, China’s gleaming international port city, two districts budgeted around 600,000 yuan each to purchase phone scanners and data-ripping tools. Beijing’s railway police budgeted a similar amount, the documents show.

“Right now, as I understand it, only two provinces in the whole country don’t use these,” said a sales representative at Zhongke Ronghui Security Technology Co Ltd, a Shaanxi-based firm that produces the XDH-5200A, one of the scanners detailed in several police procurement documents.

The representative said police stations across the whole country could consult a centralized repository of extracted data. “Almost every police station will have the equipment.”

Chinese-made devices cost as little as about 10,000 yuan for smaller ones, to hundreds of thousands of yuan for more sophisticated ones, according to prices seen at a police equipment fair in Beijing earlier this year.

The scanners have not been immediately apparent in cities like Shanghai and Beijing.

At recent checks at Beijing bus and train stations, and the heavily guarded Tiananmen square area, there were no signs of the devices. But a police officer at Beijing Railway Station confirmed they “have access when needed” to smartphone forensic technology.

Scanner data

These sorts of scanners are used in countries like the United States but they remain contentious and security forces need to go through a lengthy legal process to be able to forcibly break into a suspect’s phone.

In China, while a number of firms say they have the ability to crack many phones, police are generally able to get users to hand over their passwords, experts say.

The procurement documents show some police stations asked for tools that can pull data from a phone user’s accounts on Twitter, Facebook and its WhatsApp chat service, Google Chrome browser and Japan’s Line messaging platform.

A May 25 filing from a customs bureau in Beijing budgeted 5.7 million yuan for smartphone forensic tools from two providers, Meiya Pico and Resonant Ltd. It listed messaging platforms and “overseas” apps the devices could read.

“Basic content collection functions” must include “mobile phone passwords, address books, call history, SMS records, MMS, pictures, audio and video data, calendars, memos and mobile app data,” the document said.

Others listed tools that can breach well-known smartphone brands such as Samsung Electronics, Blackberry, China’s own Xiaomi and Huawei, as well as Apple’s tough-to-crack iPhone. Samsung, Blackberry, Xiaomi and Huawei did not respond to requests for comment. Apple declined to comment.

Wu Wangwei, an engineer at the Beijing-based Dasi Kerui Technology, which trains police personnel to use the scanners said the equipment had become “very common.”

“The smartphone has become the most important source of evidence,” he said. Police will always use it “if the case needs it.”

Chinese court cases often cite “electronic investigations,” including the collection and accessing of smartphones and tapping into social media accounts, but it is unclear what forensic equipment is involved.

Expanding outward

China spent roughly 1.24 trillion yuan on domestic security in 2017, accounting for 6.1 percent of total government spending and more than was spent on the military. Budgets for internal security, of which surveillance technology is a part, have doubled in regions including Xinjiang and Beijing.

“A good bunch of that went to some very obscure, miscellaneous security spending categories … including technology,” said Adrian Zenz, an academic who specializes in Chinese security spending.

According to two officials at the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, including one who worked on police projects in Xinjiang, surveillance techniques are tested in the region before being rolled out in other provinces.

The projects get both public and private financing. Those that have been tested in Xinjiang and later adopted in other provinces include surveillance camera systems, database software and smartphone forensics hardware, one of the officials said, requesting anonymity because the plans are not public.

“Even if it is not the original plan, if the technology can be tested then it will be cheaper so it can easily be deployed some other place,” the person said.

Cracks in the machine

China’s high tech surveillance gadgets, sometimes referred to as “black tech,” often make the headlines. They include police glasses with built-in facial recognition, cameras that analyze how people walk, drones and artificially-intelligent robots.

A fast-growing industry has developed supplying the government’s surveillance needs, propelling firms like the camera maker Hangzhou Hikvision and SenseTime, a fast-growing facial recognition firm.

The scanners though are key to harvesting data from individuals, whether on the militarized streets of Xinjiang or behind closed doors in Shanghai or Beijing.

In a cramped training center at Jundacheng Technology in Beijing’s tech district, engineers showed Reuters one such machine: a gray, shoebox-sized computer that was hooked up to and ostensibly extracting data from a Samsung smartphone.

The training firm is one of many that has cropped up to meet a demand for surveillance tools from military, police and private firms.

The scanner was made by Cellebrite, an Israeli company, but firms including Xiamen Meiya Pico, Hisign Technology and Pwnzen Infotech also make versions widely used in China. Marketing materials promise the ability to crack into most smartphones, including iPhones.

The hype though can run beyond the reality, experts say.

Chinese scanner makers often tout the ability to crack smart phone security systems, including Apple’s iPhone, but industry insiders admit this usually doesn’t mean the latest models.

“I can only recover older iPhone versions, the most recent ones I can’t,” Zhang Baizheng, who heads digital forensics training school Beijing Judacheng, told Reuters during a recent visit to the center.

Apple is also taking steps to stop devices like those used by Chinese police from cracking its phones. New versions of its iOS operating platform disable the USB port after an hour without password access, blocking a key cracking route.

According to one of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology officials, such security precautions may not matter.

Most people in China would comply with police requests to unlock their devices, he said.

“In China, it’s not wise to refuse.”

By Cate Cadell/Reuters

Reporting by Cate Cadell; Editing by Adam Jourdan and Philip McClellan.