Separated from their kids by deportation, these parents raise their family long-distance

Maria Mendoza sits in the living room with her daughter in their Oakland, California, home on Aug. 16, 2017, hours before she and her husband leave Oakland for Mexico.

In the winter of 1990, a plane carrying a small group of passengers crashed on a high-altitude plateau in Mexico.

For Maria Mendoza, the accident started a chain of events that sent her on a northward journey to Oakland, California, and, years later, back to her hometown in the central Mexican state of Hidalgo.

Sitting in her mother’s living room in Hidalgo, Mendoza reflected on the nursing career and family she built in California, and the deportation that has taken her away — unexpected outcomes of that long-ago crash.

Related: A family tries to immigrate to the US, but first, they must live separate lives

She was just 18 the day the plane went down, and had already earned an accounting degree and had a good secretarial job in a hospital near Mexico City. In addition to answering the phones, a doctor often called on Mendoza to help attend patients, including the pilot injured in the plane crash. Mendoza helped get the pilot the blood transfusions he needed. His uncle was so grateful that he offered Mendoza housing with his family in Tijuana and a better hospital job there.

Opportunities had never fallen into her lap. Born in Santa Mónica, a small village in Hidalgo with just over 100 residents, Mendoza grew up with a father who farmed the land and resented the fact that most of his children were women. At age 14, Mendoza went to work and put herself through school in the Mexican capital.

“I had to raise myself,” Mendoza said.

Off to Tijuana

Mendoza took the bus to Tijuana, hoping to advance her career. But when she arrived at the border city, she said that the pilot’s family refused to take in a stranger. Mendoza said that they abandoned her.

She found a job exchanging foreign currency in Tijuana. Sometimes, Mendoza would walk on the bridge above the Tijuana River and watch Border Patrol agents patrol the California hills.

“I never understood why people would want to risk their lives trying to cross the border into another country,” Mendoza said. “That wasn’t part of my dream.”

Love changed things.

While living in Tijuana, Mendoza began exchanging letters with an old boyfriend, Eusebio Sanchez, who had also grown up in her hometown. At age 18, Sanchez had crossed the border illegally and had settled in Oakland. Soon, Maria got a tourist visa to visit and eventually decided to stay. They began a life together as young undocumented people in California.

Now, nearly three decades later, the couple owns a three-bedroom home in Oakland, which also houses their four children.

But the parents are more than 2,000 miles away, deported to Mexico and now living in their home state of Hidalgo.

Mendoza is now 47, with wavy brown hair. Every afternoon, she and her husband video-chat with their kids in Oakland.

“How was school, baby?” she asked her 12-year-old son, Jesus, one recent evening.

“School was good,” he said, his voice crackly over the line. The internet connection in rural Mexico frequently fizzles and cuts calls.

The children range in age from 13 to 24. As a young woman, Mendoza went back to Mexico to give birth to her first child, Vianney. Then she crossed back into California with the baby, without papers. The rest of the couple’s children are US citizens. Vianney, now 24, is protected by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, an Obama-era initiative that offers work permits and some protection from deportation to certain undocumented immigrants who came to the US as children.

Now Vianney takes care of her siblings in California while her mom and dad parent long-distance.

Nearly 6 million US citizen children live with an undocumented relative. And every year, thousands of their parents are deported, according to several reports issued by the Department of Homeland Security.

Years of immigration check-ins

Several years ago, the parents tried to avoid deportation by attempting to adjust their immigration status. Their son, Jesus, was born with congenital heart disease and the couple argued in court that he would suffer extreme hardship if his parents were ever deported.

Both parents were granted work permits in 2002 as their case slowly worked its way through the courts. While they waited for a decision, Mendoza studied nursing and eventually became an oncology nurse in Oakland.

In 2011, a judge ruled that the parents could not prove that their children would suffer enough hardship to justify giving them legal residency. During the Obama presidency, both parents were granted stays of deportation and were able to renew their work permits.

Last spring, they received news that they would be deported in 90 days as part of a shift under President Donald Trump to make more undocumented immigrants subject to deportation.

The couple returned to Mexico in August 2017 and have lived with family in their hometown of Santa Monica for nearly a year. No proof of hardship experienced by their children could save them.

“I guess nobody thought about the significant amount of emotional distress that the kids are going through right now,” Mendoza said. “That’s already a hardship in itself.”

Santa Mónica is a quiet town with a cemetery, a school and a few stores, set among prickly pear cacti and mesquite trees about two hours north of Mexico City.

On a recent afternoon, while at her mother’s home, Mendoza pestered her son over the phone to prepare for an upcoming exam at his Oakland middle school.

“You have to eat a very good breakfast before you go off to school,” she told Jesus. “No excuses.”

After hanging up each day, she said that she can breathe easy for a moment, knowing all the kids are safe and sound at home. She has spent hours researching how she might get a US visa to return. But parents are currently barred from returning to the US legally for 10 years. For work, the father, Eusebio, works on his parents’ sheep farm, while his wife researches how they may be able to return to the US.

Meanwhile, the deportation is taking a physical toll. Mendoza has grappled with depression and a heart condition that she said is getting worse. The whole process, dating to Trump’s election, has been devastating, she said.

“The night of the elections, as the map was turning red, it was like if somebody was stabbing me little by little,” Mendoza said.

After Trump’s election, she began working extra shifts at the hospital to save money for the kids in case she and her husband were deported. She figured every day of work could pay for one week of food for her kids.

The extra money is now vital but the parents know their savings will run out and that, soon, their kids must pay the mortgage.

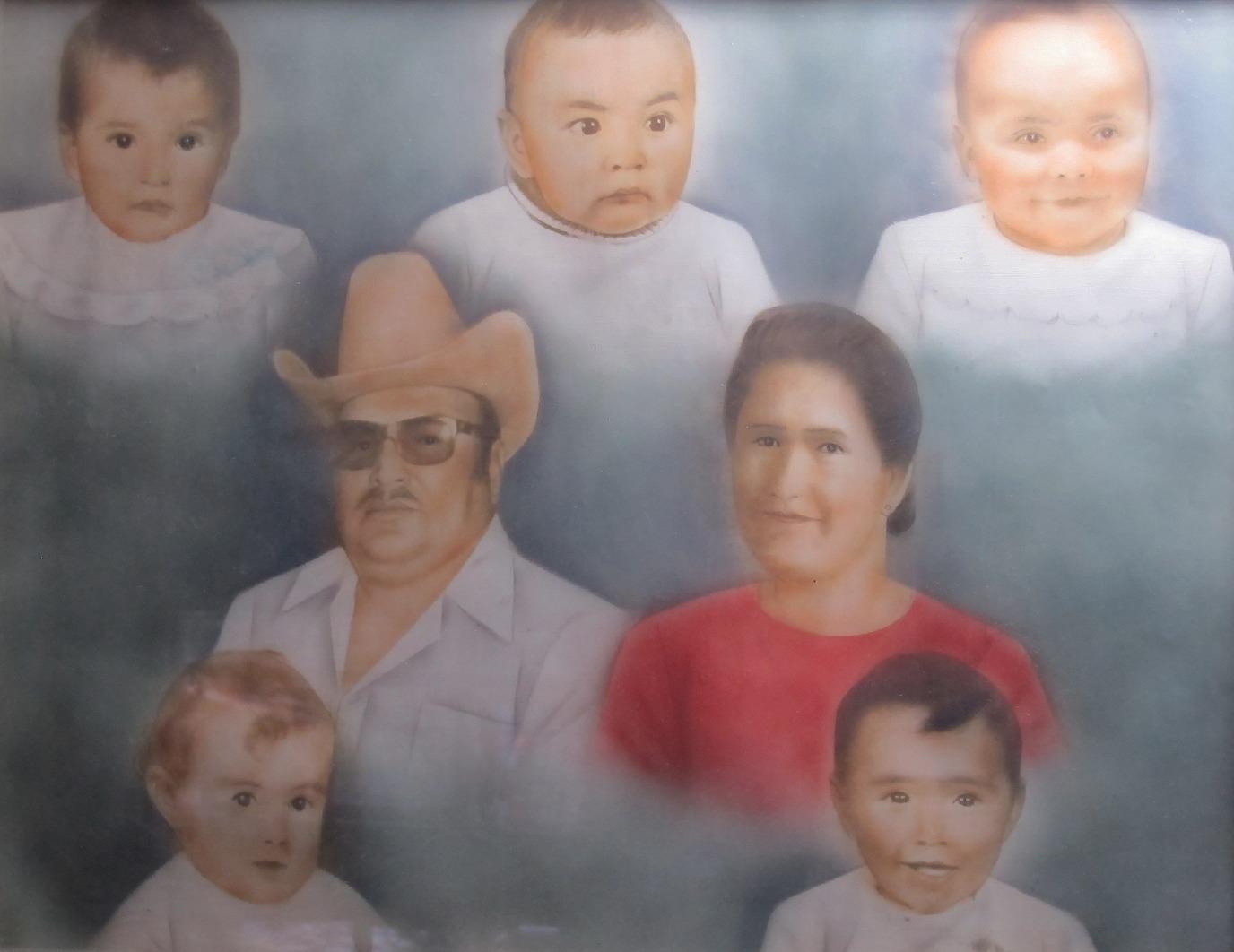

Back in Oakland, the four siblings live together in the family home, along with a flock of chickens out back. Inside, family photos fill the living room. There is a large kitchen table where the family used to gather.

Not long ago, Vianney was a college student. Now she is the one who does the Costco runs, drives her siblings to school and cooks the meals. All of these new responsibilities have helped Vianney understand and respect her mother more. But parenting weighs heavily on her.

“I can’t afford to let anything happen to me,” Vianney said. “I don’t know what would happen to my siblings if I wasn’t here.”

Before her parents were deported, Vianney thought about following in her mother’s footsteps and becoming a nurse. Now her dreams are on hold.

The parents thought about bringing their kids to Mexico, but Mendoza said that they have far more opportunities, including better schools, in California. Many people in their town in Mexico raise sheep, herding flocks along dirt roads.

Related: ‘I lost trust in the system,’ says US citizen now unable to reunite with his Yemeni family

Mendoza still hopes that she can find a way back to her kids in California. Her old employer, Highland Hospital in Oakland, has applied to bring her to the US on an H-1B visa for skilled professionals. But those visas are chosen through a competitive lottery system. It is a long shot. And if she were granted a visa, she would have to win an exemption to the bar against returning to the US.

Both parents said that their deportations have forced their family to become stronger. Mendoza added that she no longer sees herself as a victim of immigration laws that separate families.

“The system is broken,” she said. “It just happened to be that I was there when that broken system became even more broken.”