After four years of conflict in eastern Ukraine ‘women do better’ than men when it comes to rebuilding their lives

Giulnara Asanova stands on the balcony overlooking the courtyard of the building she lives in outside of Kiev. She’s originally from Crimea and moved here because Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

Giulnara Asanova and her husband remember when they decided to leave Crimea.

“We sat down at the table and decided what to do,” she says, speaking Russian through a translator. “We decided to save our children, save our grandchildren. We saw the tanks, we saw weapons and military.”

That was in 2014.

Asanova, her daughter, son-in-law and three grandchildren left for Kiev. They thought it would only be for a few months. Now, four years later, Asanova and her family are living in government-subsidized housing, 30 minutes from the center of the capital, in an old Soviet block apartment building.

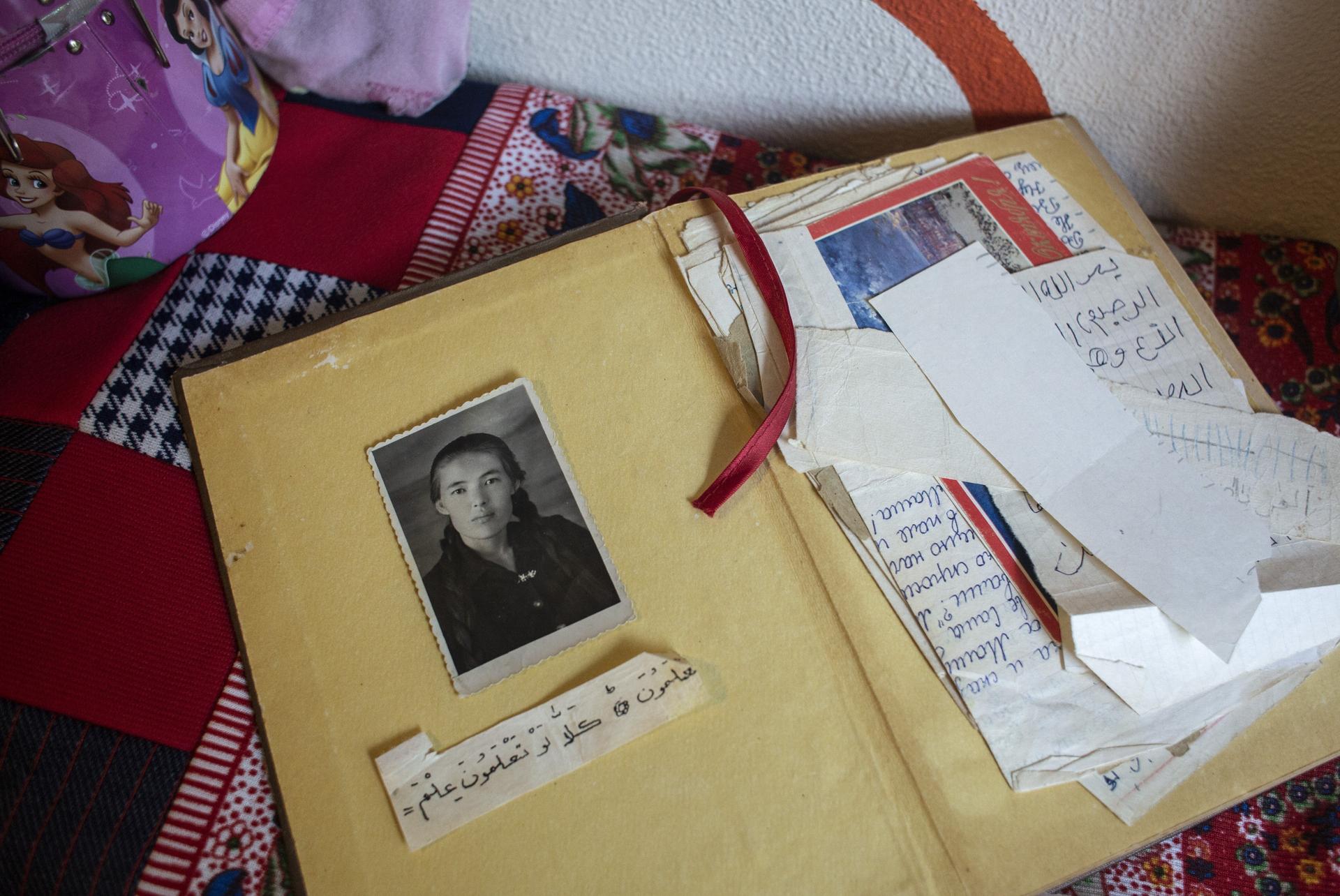

She traded a six-room house and a seven-minute drive to the Black Sea for three tiny rooms for six people. Her husband stayed behind to take care of their house while Asanova left with her child and grandchildren. In these three rooms, she’s tried to make it like home. An embroidered cloth hangs from the wall that says, “Can Dostum,” Turkish for “Good Friend,” along with two figurines of a grandmother and a grandfather fishing — it’s supposed to represent her and her husband. But she misses her home.

“This is our tradition,” she says. “This is how we do things. I grew up in a big family as well. My grandmother took care of everybody. My mom took care of everybody. Now I am doing this.”

Asanova and her family are not alone. According to the Global Conflict Tracker, more than one million people have abandoned their homes in eastern Ukraine and more than 10,000 people have died since the conflict began in 2014.

Who’s leading these displaced families to safety? Women like Asanova. She and other women are taking charge and moving their families to new and unfamiliar communities so they can find peace and safety. Some traded good jobs and new apartments for an unfamiliar life in rural villages, far from home. They live among strangers, face discrimination and struggle with poverty.

But the women of eastern Ukraine are tough. They “do better” than men, says one nonprofit in Kiev that helps families rebuild.

This is not the first time Asanova has suffered the pain of exile. Her family members are Crimean Tatars, an ethnic minority with a history that dates back more than 1,000 years in the Crimean Penninsula. That’s why Russia’s annexation of Crimea is such a blow. This is where Asanova‘s people are from.

Her family was forced to abandon their home right after World War II under Joseph Stalin’s Soviet rule. She grew up in Uzbekistan and finally moved back to Crimea in 1989.

When she did move back, she and her husband lived in a tent as they built their house.

“I was actually quite impressed with myself,” Asanova says as she dusts flour off a small table in her makeshift kitchen. “I said to myself, ‘How could I stand this?’ but I guess I was young and optimistic back then.”

She seems less optimistic that she will be able to return now, even though she is anxious to do so.

Meeting Asanova, one would never guess she is full of worry. She has barely a line on her face. She insists on wearing lipstick for photos and, even though she’s preparing to cook chicken for dinner and bustling around arranging fresh trays of apple jam pastries, she still has time to make Turkish coffee. It’s part of her traditions — what women did before her.

Asanova has only seen the house she and her husband built once in the past four years. She went to visit him in 2016. While traveling to Crimea, soldiers pulled her off a bus and interrogated her for almost an hour, she says. They asked her questions about where she’s from and who her family was. Eventually, she was let go. The bus driver waited for her, but the encounter rattled her.

According to Human Rights Watch, stopping, searching and intimidating people is a routine affair for Crimean Tatars like Asanova. Since Russia annexed Crimea, there have been arrests of people suspected of being terrorists as well as persecution and intimidation of Crimean Tatar media and other members of the community.

This is always in the back of Asanova‘s mind as she spends her time in Kiev, wondering about her husband and her house. She spends her days trying to keep her mind off of things by doing embroidery, baking and taking care of her grandchildren. She doesn’t think she will be able to return to Crimea, at least until it becomes part of Ukraine again. She says she has high hopes that other nations will step in and, “fight this monster,” meaning Russia.

“We have big hopes and expectations of the US as the world’s policeman. They are the only one who can stop this,” she says.

Getting help

On the other side of town is the office of Svoi, which, in Russian means “All of us.” It’s a charitable organization that was set up when the conflict started four years ago to help people resettle. This single office is no larger than a bedroom, yet it hums with activity. Several people click away at computers, another volunteer is handing out toiletries to people and a few students are studying for a certification test.

Svoi has helped thousands of people get jobs, find places to live and get government assistance. The woman in charge is Oksana Sukhorukova.

“From my experience — from the things that I saw here — women do better. They have the strength to stand up and go and do something,” she says of how conflict has affected people.

It’s the men, she explains, who’ve had more of a rough time with this conflict. She recalled one man who hung himself because he didn’t have enough money to feed his family.

“We’ve had the thoughts to make special workshops for men under 40 years of age, because we have witnessed lots of suicides from them,” Sukhorukova explains.

When the conflict started, they were helping a little more than 3,000 people per month. Now, it’s down to about 1,000 every three months. At the moment, Svoi is helping a lot of families with children with disabilities and cancer. Those are the people who face the biggest hurdles, Sukhorukova says.

“So, as they say, in happiness, they are all the same, but problems, they’re all different,” she says. “We have lots of different stories, especially about mothers with children with disabilities who come here. Some of them settle here and provide help for their children and also for other people. Some of them return back as it’s getting more and more complicated to settle here.”

What Sukhorukova means by complicated is that it’s getting harder to find work and housing.

Other destinations

Kiev isn’t the only place people have resettled.

A three hours drive from the capital sits the village of Zelena Polyana. It’s surrounded by a breathtaking field of lavender and thick, green forests. Large stork nests can be seen every few miles sitting atop electric poles. Small, clapboard Orthodox churches painted white with green and blue trim dot the landscape as roads get more narrow.

This is where Elena Kachalina, her 25-year-old daughter Inna Chudakova, her grandson Arthur, and her nephew Misha, live. They’re from the Donbass region in the east part of the country, bordering Russia. After Kachalina’s apartment was hit by a mortar and destroyed by a fire, they decided to leave. That was in 2015.

They had no home. No papers. And like so many, they had no place to go.

Since then, there have been numerous ceasefires in the Donbass region — including one agreed to earlier this month. But a truce has yet to hold and fighting continues.

First, they tried to live in Kharkiv, a region about four hours away, but it didn’t work out.

Then Kachalina remembered Zelena Polyana. Her husband came here a long time ago and she had some friends in a nearby village. She didn’t like it at first and said she wanted to return home, but then, she found the place they are living in now. It had been abandoned for eight years and needed some pretty big repairs. Now, Kachalina says there is no way she is returning to Donbass.

“It’s grey and unpleasant,” says Chudakova.

And Kachalina agrees.

“We have nature, forests here, lakes here. Mushrooms and berries. You can hunt and fish. Where is the point to return?” Kachalina asks.

The place where Kachalina lives — it’s rent free.

Here’s why: It’s in an area of testing and surveillance for radioactive damage and poisoning. It’s near Chernobyl, the site of one of the world’s worst nuclear accidents. The village had been abandoned, but slowly people started moving back. Like Kachalina.

On April 25, 1986, near the town of Pripyat, the Chernobyl nuclear plant’s reactor No. 4 exploded, sending clouds of radiation throughout Europe. Over the last 30 years, scientists have studied the effects of that radiation on wildlife, soil and plants. Scientists PRI spoke with said that some vegetables, like mushrooms, will contain more radiation and are more dangerous to eat than others. The government created an exclusion zone, a roughly 1,000-mile area around the Chernobyl facility, to prevent people from living in the most hazardous areas.

Some towns will remain abandoned forever and will never be inhabitable. Scientists in Kiev test the soil in Zelena Polyana regularly for contamination and say it is mostly safe. Kachalina says she isn’t worried.

“It’s better to live with radiation than having a shell hit your house tomorrow,” she explains.

They are raising chickens, a pig and tending a garden with potatoes and other vegetables. Both mother and daughter have found jobs.

“I’m settled here. I have family, a job, a house and my son will go to [first grade] next year,” says Chudakova, who will be a teacher at her son’s school.

They feel welcome here. When they first moved into their house, they had no pots to cook with, no furniture, so neighbors came and donated some stuff for them to use.

“We are like locals now,” says Kachalina as she laughs and smokes a cigarette outside in the courtyard of their house.

It’s an adjustment

It’s been a huge adjustment for both families. For Kachalina and her daughter, they left behind jobs and a new apartment in the city for a quiet, village life among fields and forests. For Asanova, back in Kiev, she went from a huge house near the ocean to a couple of tiny rooms in a worn down apartment block.

Here’s the thing: Asanova really wants to go home, but she can’t. She doesn’t really have a choice because Crimean Tatars are increasingly unwelcome in a territory they once called their ancestral homeland. Now that it’s been annexed by Russia, Asanova can’t go back to the home she and her husband built by hand.

She’s built a new community in Kiev with her grandchildren and wants Safia, the youngest, to be safe. But she’s without her husband.

“We are determined to go on and live here, despite the fact that we are on two different ends of this tragedy,” Asanova explains.

Kachalina is in a different situation. It’s still dangerous where she’s from, but she doesn’t really have any stake in what she left behind. Chudakova left her husband in Donbass and doesn’t expect him to join her in Zelena Polyana, and she’s OK with that. They think this new life in the village is better for them.

“We had nothing when we came here,” says Kachalina. “But step by step, piece by piece, we renovated this place and now, together with my daughter, we have enough money to buy a house. And we did this ourselves.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?