Poland forces Supreme Court judges into early retirement

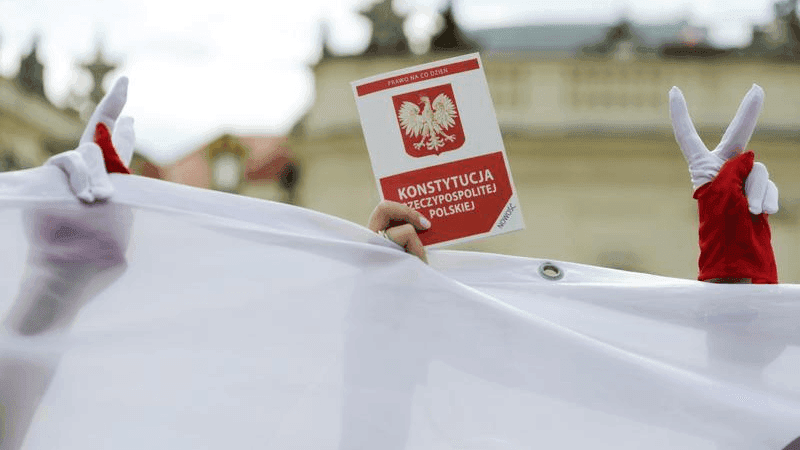

A demonstrator holds a copy of the Polish Constitution during a protest against the judicial reform outside the Presidential Palace in Warsaw, Poland, July 3, 2018.

On Tuesday, Poland enacted a controversial new reform to its Supreme Court forcing nearly 40 percent of its judges into early retirement in what observers say is the latest in a string of attempts by the nationalist government to control the country’s judiciary system.

The new law, which has triggered countrywide protests in recent days, comes less than 24 hours after the European Commission notified the Polish government that it has begun infringement proceedings into the matter.

According to the law, the mandatory retirement age of Supreme Court judges will be lowered from 70 to 65, prematurely ending the terms of 27 of the 72 judges, including the first president of the court. Those vacancies will then be filled by President Andrzej Duda, an alley of the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS).

The judges will have until midnight tonight to hand in their resignations.

“It is a sad day,” Małgorzata Gersdorf, the country’s highest-ranking judge as the first president of the Supreme Court, told students today during a speech in Warsaw. “It ends an epoch of the judiciary and the Supreme Court and their organizational independence and competence.”

In December, the European Commission invoked Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union, one of the two EU-founding documents — something it has never done before — in an attempt to determine whether Poland had breached the rule of law. Following a three-hour hearing between Polish officials and the General Affairs Council in Luxembourg last week, the European Commission determined that it had.

“The Commission is of the opinion that these measures undermine the principle of judicial independence, including the irremovability of judges, and thereby Poland fails to fulfill its obligations under Article 19(1) of the Treaty on European Union,” the European Commission wrote in a statement yesterday.

Polish officials, meanwhile, have consistently defended the law as a mechanism meant to root out corruption that has been in place since the fall of communism 30 years ago.

“Today’s discussion between #EU member states was very factual. We have exhausted our arguments regarding the reforms of the Polish judiciary,” Poland’s secretary of state for European Affairs, Konrad Szymański, wrote in a tweet following the meeting.

Not everybody is convinced that the government’s intentions are as noble as they claim. Kamila Gasiuk-Pihowicz, a member of parliament for the opposition Modern party, said that giving the PiS allied president the power to fill vacant seats in Poland’s highest court would politicize an institution that is charged with validating elections.

“It isn’t an accident that the chamber to which there is a need to appoint new judges is exactly the chamber that takes on the constitutionality of Polish elections,” she said. “I am really afraid of what the result will be now that they have shown they do not trust in the law and institutions like the Supreme Court.”

But the new law also creates a new appeals chamber within the court that could reopen cases dating back 20 years at the request of a government-appointed prosecutor-general.

The Supreme Court is not taking the matter lying down. Last week, the judges, including Judge Gersdorf who insists that her term runs until 2020, said they would resist the law and would turn up for work on Wednesday as per usual, setting up a potential standoff between the two sides.

Joining them in protest are thousands of Poles who have taken to the streets in countrywide protests in recent days. Last night in Warsaw, hundreds of people gathered in front of the Supreme Court waving placards chanting slogans like “we will not let go,” “constitution” and “free courts.”

“The case of the Supreme Court is crucial to the entire nation,” said activist and grandmother Julie Walecka told PRI. “I should be at home playing with my grandchildren and enjoying my life, but you cannot be sitting at home when something like this is happening.

“Unfortunately, this all wrongly resembles what happened in this country 50 years ago,” she said, referring to the communist era.

This is not the government’s first attack on the judiciary. Since sweeping to power in 2015, PiS has decimated the Constitutional Court and last year launched a state-funded campaign attacking judges on billboards all over the country, drawing claims of harassment and intimidation.

“There were thousands of these ads across Poland and on television. It was a huge enterprise. Some of the cases were maybe described accurately, but also misinterpreted. It is an awful kind of hate speech,” said Dariusz Mazur, a judge of a regional court in Krakow who is also the spokesman for a local association of about 200 judges.

“This is totally completely unprecedented, and not only for Poland,” he said.

But the attacks go deeper than just the judiciary. The anti-migrant government has used xenophobic rhetoric to isolate opposition and has also relentlessly sought to control the media.

In 2016 President Duda signed a law that allowed the government to appoint new heads of public media and civil service institutions. Journalists, meanwhile, are subject to threats and even imprisonment, while independent media outlets have been slapped with hefty fines.

Government repression of Poland’s democratic institutions has been the topic of constant criticism from the EU, international organizations and human rights organizations.

“In the past two years, the Polish government, led by the PiS, has step by step eroded the independence and effectiveness of its judiciary,” Philippe Dam, advocacy director for Europe and Central Asia at Human Rights Watch, told PRI.

“Let’s not be fooled, the law of the Supreme Court is part of a larger agenda to get rid of judges seen as critical and to politically take over the country’s judiciary. Once checks and balances are eroded, it puts other human rights like free expression or women’s rights at serious risks.”

With the EU Commission now moving ahead with infringement proceedings against Poland with regards to the Supreme Court reform, feelings are mixed on whether they will have an impact.

“We will have to wait for the EU, but … in more than two years we have seen only four recommendations from the EU Commission. They have shown they are reluctant to move on Poland. It has been massively disappointing,” said Adam Belcer, a Poland political expert at Warsaw-based think tank WiseEuropa.

He said the situation in Poland can be likened to Hungary where Prime Minister Viktor Orban has used an anti-migrant platform to carry out an increasingly autocratic agenda.

Related: In anti-migrant push, ‘Stop Soros’ laws passed in Hungary

“From a legal point of view, we can say the Hungarian position is on stronger footing, so what is happening in Poland is that we are trying to catch up,” he said. “The Polish government is trying to achieve the same goal, but faster, and without the two-thirds majority in parliament [that Hungary has], so that’s why we are on a collision course with the European Commission.”

Others, meanwhile, are more hopeful.

“We have to have confidence in them, otherwise where can we appeal? We are in the EU and are a kind of family. I believe that we should be given support from that and the state should act accordingly,” said Walecka.

Philip Heijmans reported from Warsaw.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!