Why the debate continues over repatriating looted Ethiopian treasures

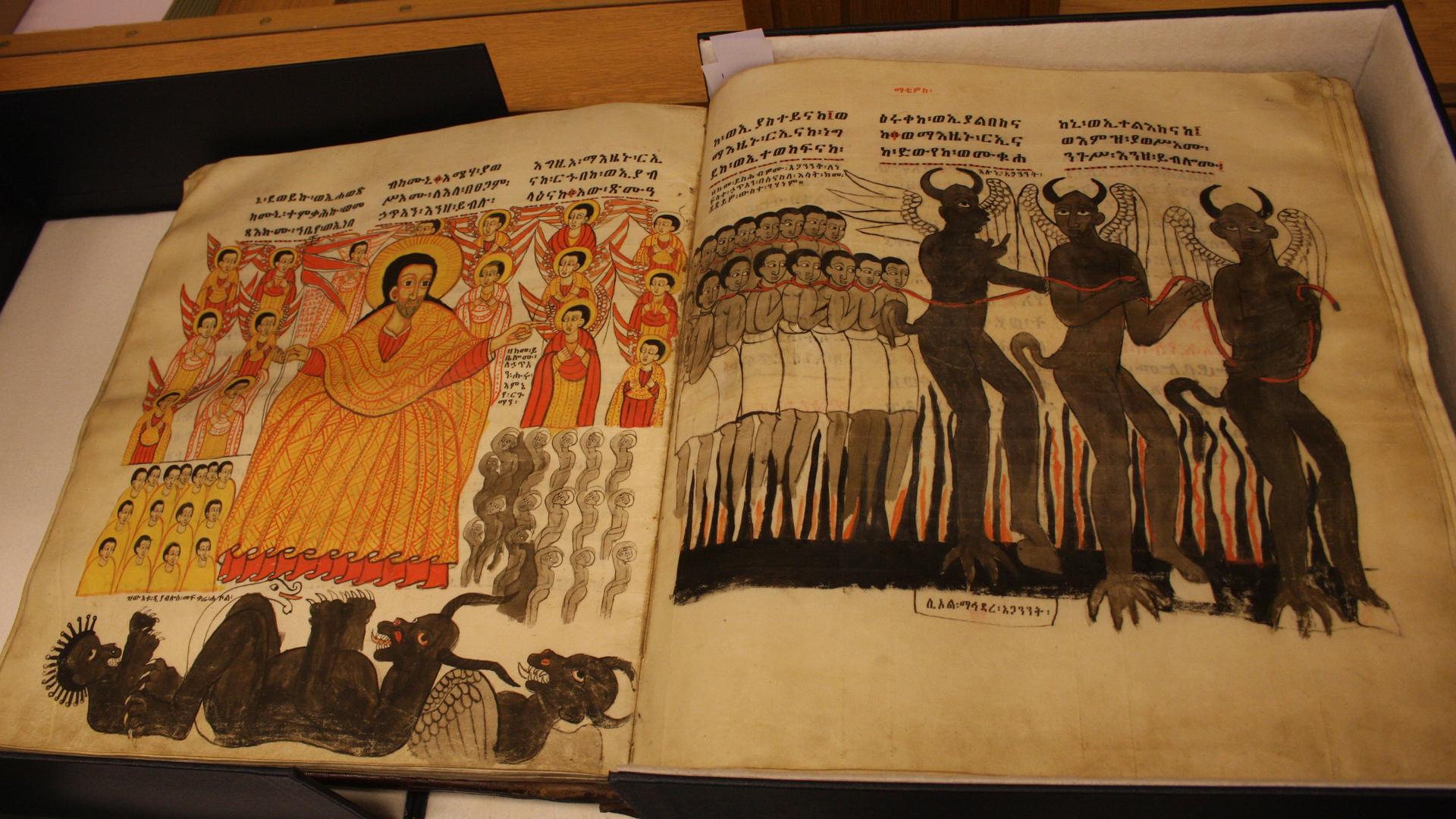

Manuscripts from Maqdala at the British Library in London.

The yellow card saying “New Acquisition” beside a 19th-century necklace in a glass case within the Institute of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa barely hints at the remarkable story and controversy surrounding the simple-looking artifact and other far more resplendent items related to it.

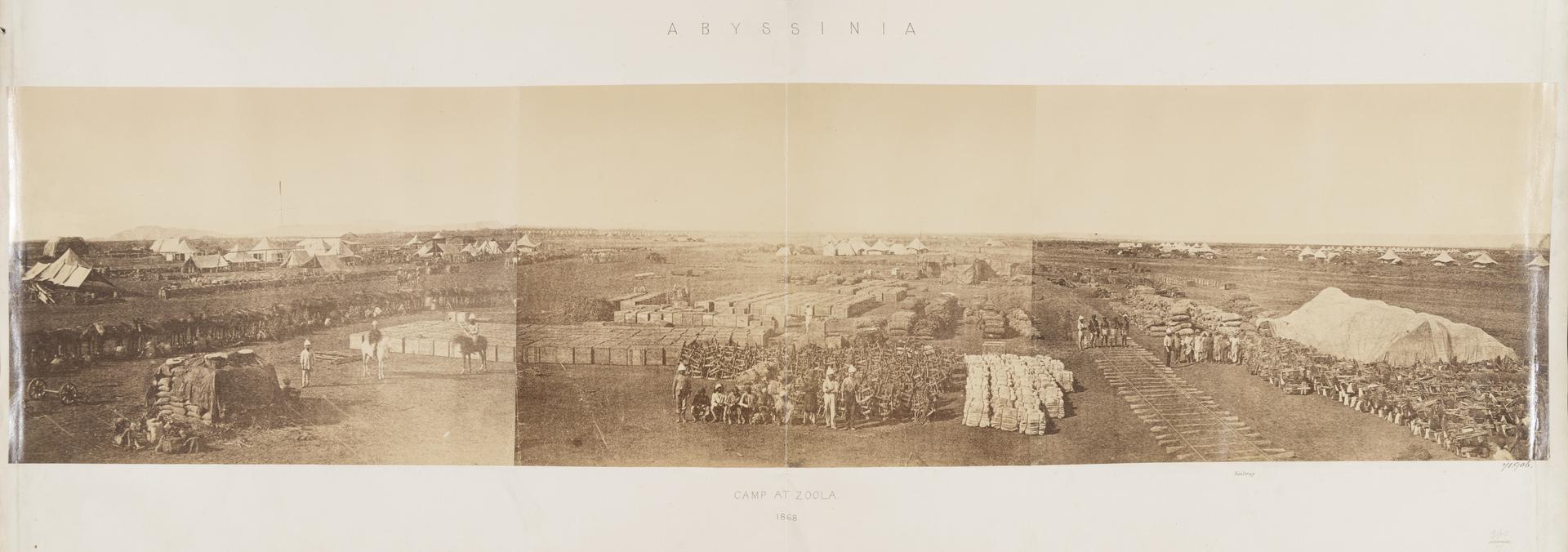

The necklace was given to the institute by the descendants of Robert Napier, one of the most famous British generals of the imperial era, who in 1868 led an expedition to release British hostages being held in then Abyssinia by Emperor Tewodros.

After defeating the emperor’s forces and ransacking his mountaintop fortress at Maqdala, the victorious troops carted away — on 15 elephants and hundreds of donkeys — looted treasure to the Horn of Africa coast and back to the UK.

The complex issue of what to do with art and objects looted from Africa and now residing in museums across America and Europe has dragged on without resolution for years, though recently there appears an increasing willingness to engage with the conundrum at various levels.

Last November, during a visit to the West African country of Burkina Faso, President Emmanuel Macron of France described the restoration of African artifacts as a “top priority” for his country and that “African heritage cannot be a prisoner of European museums.”

Meanwhile, at the start of April, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum opened a new exhibition, “Maqdela 1868,” to mark the 150th anniversary of the battle and to confront the collection’s controversial background.

“They are stunning pieces with a complex history,” says Tristram Hunt, the Victoria and Albert museum’s director. “We want to better reflect on the history of these artifacts in our collection — tracing their origins and then confronting the difficult and complex issues which arise.”

The looting caused much consternation in England at the time. Prime Minister William Gladstone condemned the taking of treasures from Maqdala and “deeply lamented, for the sake of the country, and for the sake of all concerned, that these articles … were thought fit to be brought away by a British army,” Hunt says. Gladstone urged that they “be held only until they could be restored.”

In addition to the necklace returned by the Napier family, there have been other notable restorations over the years. A famous biblical text, the Kebra Nagast, was released by the British Museum in 1872 to the new Abyssinian King Yoannes, on the order of Queen Victoria herself. An imperial crown, throne, cap and seal have also been returned. But these have been exceptions to the general rule.

In 2007 former Ethiopian President Girma Wolde-Giorgis made a formal request for the return of the remains of Theodore’s son Alemayehu who, following his father’s death, was taken to Britain aged 7 to be looked after. He succumbed to illness, dying aged 19 and is buried at Windsor Castle.

“The inclusion of [a photo of Alemayehu] in the display juxtaposes Alemayehu with some of the other great treasures taken from Ethiopia, reminding us that not only material possessions were lost to the British forces,” Hunt says.

Girma’s request was reportedly turned down based on potential damage an exhumation might cause to the surrounding graves.

“Why are the remains of Prince Alemayehu still in Britain?” says Alexander Herman, assistant director of the Institute of Art and Law, an educational organization focused on law relating to cultural heritage. “After years of requests, the monarchs have responded either by refusal or silence. But perhaps the time has come to do the honorable thing and return the remains to the country with the most obvious historical and cultural connection to them.”

Before his death in 2017, the historian Richard Pankhurst, recognized as arguably the most prolific scholar in the field of Ethiopian studies and who spent much of his life in Ethiopia, had long campaigned — unsuccessfully — for the return of about 350 manuscripts taken from Maqdala that ended up in the British Library (he was successful with the restoration of a giant obelisk taken by the Italians in 1937 being returned to the northern Ethiopian city of Axum in 2005).

“The British Library is responsible for preserving, researching and providing access to the collections in our custodianship,” says Luisa Mengoni, head of the library’s Asian and African Collections. “Our priority is to make the library’s collection of Ethiopian manuscripts fully accessible on-site and online so that they can be researched and viewed by as many people as possible from across the world.”

The ongoing debate sees technology playing an increasing role.

“The technology of replicas now makes it easy to reproduce objects such as manuscripts and copies could be left in UK institutions and the originals sent to Ethiopia, or, if not acceptable, the reverse for now, with the possibility of exchange of replicas for originals later,” says Alula Pankhurst, the son of Richard Pankhurst and an Ethiopia expert himself.

But the role of technology is seen differently by those at the British Library.

“We have both a growing opportunity and growing responsibility to use the potential of digital to increase access for people across the world to the intellectual heritage that we safeguard,” Mengoni says. As a result, she explains, during the next two years the library aims to digitize some 250 manuscripts from the Ethiopian collection, with 25 manuscripts already available online in full for the first time through its Digitised Manuscripts website.

Another potential dilemma over whether artifacts are loaned or returned to their lands of origins is how museums currently housing items decide whether African institutions are fit to take care of such artifacts. This approach, however, is problematic for some, who argue it expresses a paternalistic attitude toward Africa that smacks of “neo-colonialism.”

“It’s true that the level of care and quality in Britain is much better than ours, but if you come to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies you can see how well [items previously returned] are kept and made available to the public,” says Andreas Eshete, a former president of Addis Ababa University — which houses the institute — and, who co-founded the Association for the Return of the Maqdala Ethiopian Treasures (AFROMET), which has engaged with the British parliament over Maqdala.

Another potential problem with restorations, some argue, is that African borders were drawn by European powers during the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 without reference to the boundaries existing at the time — hence it would be hard to decide where older artifacts belong.

The Maqdala manuscripts pose a particular conundrum as they had been looted by Tewodros himself, says Yves Marie Stranger, editor of “Ethiopia: Through Writers’ Eyes.” So the British stole already stolen items.

For now the debate continues, on the whole, relatively amiably, with cooperation already occurring between both sides. While preparing the Maqdala exhibition, the V&A Museum collaborated with the Ethiopian Embassy in London and local Ethiopian diaspora community to enable “a vital new understanding of the collection’s significance,” Hunt says.

In February 2018, the Ethiopian ambassador gave a speech at the opening of the library’s free display titled “African Scribes: Manuscript Culture of Ethiopia,” which aims to raise the profile of the tradition of Ethiopian scribes and make these manuscripts known to a wider public. The library has previously also worked with Ethiopia’s Ministry of Culture, the Institute of Ethiopian Studies and the Anglo-Ethiopian Society.

“We recognize the huge significance that the manuscripts have for many in Ethiopia and for many others around the world,” Mengoni says.

When talking to both sides of the debate, it becomes notable that at a certain level each side is united and in agreement: These objects are unique, often beautiful, represent important elements of Ethiopian culture and history, and need to be preserved and made available to educate and inform.

“While some restituionists may grumble that the majority of items have not been returned, much has been done to spread the knowledge of their existence — and great artistry — to Ethiopian scholars, and to the world at large,” Herman says.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?