The ‘valve turners’: Activists faced jail time to briefly stop the flow of Canadian crude oil

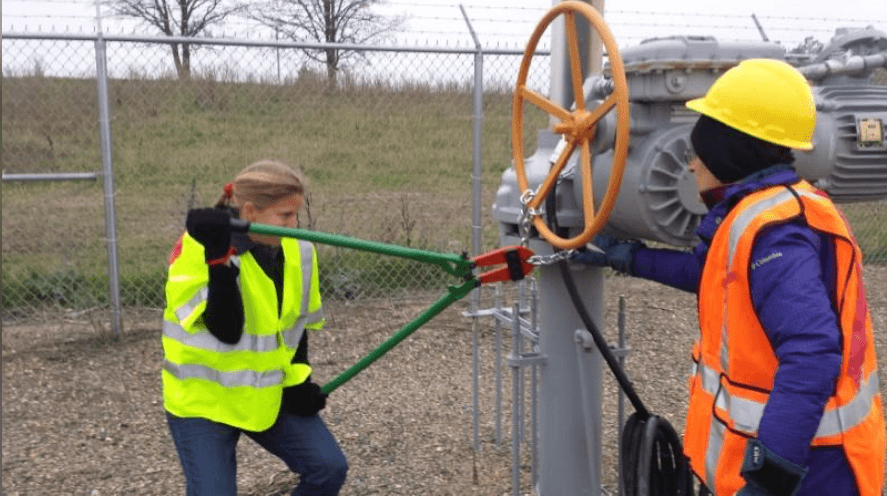

“Valve turner” activists attempt to cut chains after trespassing into a valve station for pipelines carrying crude from Canadian oils sands into the US near Clearbrook, Minnesota, in an image released October 11, 2016.

On October 11, 2016, American climate activists closed valves on five pipelines, halting most of the oil flowing into the US from Canada’s oil sands. They waited for arrest and when police arrived, they went quietly. They faced criminal charges in court.

The activists, known as the “valve turners,” argued their illegal actions constituted necessary civil disobedience in the face of the catastrophic damage humans are causing to the climate by burning fossil fuels. The cross-border pipelines in Washington state, Montana and Minnesota carried nearly 70 percent of the crude oil imported to the US from Canada. So for several hours, a large part of the United States’ oil from Canada stopped flowing.

“It was, to a large extent, a symbolic action,” says writer Michelle Nijhuis, who profiled the valve turners for The New York Times Magazine. “Michael Foster, who was the main character in my story, said he really got some visceral satisfaction from stopping what he would call poison from being emitted into the atmosphere. But strategically, I think they wanted to wake up people who were sympathetic, but complacent.”

Nijhuis says she’s been interested in environmental activists for a long time, not because she necessarily condones or agree with their actions, but “because they are so unusual. Radical environmental activists are among the few people who are really willing to disrupt their lives for issues that a lot of us see as distant or abstract concerns.”

The valve turners, however, are unlike typical radical environmental activists. For one thing, they don’t look very radical: Most of them are older — the youngest in the group is 50 years old — and most are churchgoers who “wear sensible shoes,” Nijhuis says.

“They’re all white. Several of them are grandparents,” she continues. “None of them is truly poor. Some of them are voluntarily poor, but they’re all fairly comfortable economically. And none of them is facing an immediate threat from climate change. Their houses are not flooding, their crops are not being flooded; and they all say they feel like those advantages give them a kind of responsibility to take the kind of actions that they’ve taken.”

Nijhuis describes the valve turners as “really humble people, who are not doing this because they enjoy performance or they enjoy setting themselves apart from the rest of humanity. Even the jurors I talked to who were very, very critical of what the valve turners had done, recognized that their convictions were genuine and that they were truly motivated by their convictions.”

In the 1980s and 90s and early 2000s, groups such as Earth First and the Earth Liberation Front committed acts such as sabotaging science labs and burning a ski lodge in Colorado. They would carry out an action in the middle of the night and run away, remaining anonymous. This, Nijuhuis says, allowed opponents of the environmental movement to say, “‘All these environmentalists are terrorists. We really have to be concerned about this movement. It’s out to hurt people, to cause damage.’”

The valve turners, by contrast, are committed to nonviolence. They planned their actions so that they would have the opportunity to bring their case before a judge.

“They knew they were going to cause minor property damage, but they did not want to cause major property damage,” Nijhuis explains. “Perhaps just as importantly, they said, ‘We’re going to commit these actions, and then we’re going to wait to be arrested. We’re going to show up in court, and we’re going to explain why we did that.’ They see the explanation of their motivations as just as important as what they did with bolt cutters at the Keystone Pipeline.”

Foster and his codefendant were charged with conspiracy, which Nijhuis says was surprising because his co-defendant was merely filming the events.

“North Dakota took as hard a line as possible against these activists,” Nijhuis says. “That was not the case in Washington state. So, it varies state by state. The outcomes, of course, vary judge by judge, and jury by jury. And the range of opinions that I found in interviewing jury members was really wide-ranging.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living one Earth with Steve Curwood.