Women serving time at the Ohio Reformatory for Women are offered a comprehensive treatment program called Tapestry. It helps them stay clean and make an easier transition when they finish their sentence. Lisa Duncan, Ashley Porter, Sheena Kimberly and Stephanie Cleveland, all of whom are in the program, are pictured from left to right.

It’s a chilly March afternoon in Marysville, Ohio, and I’m riding around on a golf cart with Clara Golding Kent, the public information officer for the Ohio Reformatory for Women. It’s right after "count," when officials make sure the women serving time at Ohio's oldest prison are where they're supposed to be.

Just now, the women here are heading to lunch, jobs and classes or socializing in the yard. Ohio Reformatory for Women was built in 1916 but has expanded beyond the original stone structure. Plus, nowadays, they're doing more to enable women to succeed outside the prison and hopefully stay out.

Golding Kent acts as my tour guide. "This used to be the old warden's house," she shouts over the hum of the golf cart, referring to a vacant lot we are passing by. It's being redeveloped: "We're making it into a new nursery."

You read that right. Officials are building a nursery at a prison. Pregnant women serving three years or less at ORW are allowed to keep their babies with them until their sentence is up. ORW is one of only four prisons in the US that allow children and infants to stay with their mothers while they're incarcerated.

The number of women serving time in Ohio prisons is rising. Nearly 3,000 women were imprisoned statewide in 2017, according to the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections. The figure has remained high over the last several years. One of the main reasons: Crimes related to drug addiction are going up, and more women are getting swept up in it. Some of those crimes are explicitly addiction-related, like drug trafficking. Others, like burglary, may have been committed in support of a drug habit. Additionally, Ohio is at the epicenter of the national opioid abuse epidemic that’s ripped apart families and communities, caused a huge spike in addiction-related crimes and led to a record number of overdoses.

In response, health officials, community organizations and law enforcement agencies across the state are looking for effective ways to treat women struggling with opioid addiction. They want to keep them out of prison and away from the pressures that keep them reoffending. It's a big challenge but one program seems to be working, and it's here at ORW.

The golf cart crawls toward one of the low-slung, concrete buildings, and Golding Kent tells me about Tapestry, an inpatient treatment program for women here. The women must be clean and sober to take part, and they can be at any stage in their sentence. Unlike more typical inpatient programs that last 30 or 90 days, Tapestry is an 18-month commitment.

It focuses not only on keeping the women clean and sober but delving into the root causes of their addiction and, ultimately, changing their lives. Annette Dominguez, who’s led the program for the last five years, says it’s about healing mind, body and spirit.

The program works on changing how women think about themselves and getting them to open up about some of the trauma that led them to use drugs in the first place. “It’s not just about not using drugs anymore, but it’s about changing how you think. How you think about the world. How you think about your place in it. How you think about yourself," she says, adding, "Most of the women come with serious self-esteem issues in addition to domestic violence, sexual abuse issues that they have. So, they come here with other women who have similar issues and [can] be part of the community, which in itself is an agent of change.”

Women learn how to relate to one another and to others beyond their immediate surroundings. They chat via Skype once a week with a school for children with disabilities in South Africa, to learn empathy. If someone about to be released is looking for a job, a Tapestry graduate on the outside can help them network. And the program's graduates stay in touch through a Facebook group.

Lisa Duncan and Ashley Porter are both in the middle of their sentences at ORW. Duncan has been here a few times. She's a graduate of the Tapestry program but comes back to volunteer with women like Porter who are in thick of it. Duncan lives in the same house with the women. They refer to themselves as "sisters."

"We are here to basically guide them," Duncan says of her role with the program. "I’m a repeat offender, and that’s why I think it’s very important for me to be here because the sisters will understand that if you don’t stay connected, then there is definitely another number [prison sentence] under your belt. If you don’t stay connected, you’re definitely not strong enough to stand on your own. It’s too hard. We need each other to survive.”

Porter says that Tapestry is different from other programs she's done in the past. “This is different than a 30-day program. I know that after I finish here, I’ll be able to survive with the help of my Tapestry sisters. And support my kids.”

According to a study by the CDC titled Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES), women who experience trauma such as sexual, physical or emotional abuse are five times likelier to end up behind bars than those who don't. And many of those same women will use drugs to deal with that trauma. They rely on a high to numb the pain.

That's certainly what happened to Heather Ruble.

She graduated from Tapestry before she left ORW in 2015. She was charged with two felony counts of drug trafficking and served a mandatory four-year sentence. Her daughter, Vanessa, was 4 and went to live with Ruble's parents. When I meet Ruble at her tidy, clapboard home in Lima, Ohio, she tells me how her drug abuse got out of control after her daughter was born. She was raped twice. The first time, in 2008, she was helping an intoxicated friend get home. There, a neighbor pulled her into an abandoned home and attacked her. Ruble had been clean and sober for a few years but did cocaine after the attack.

She went to a nearby Walmart to wash up before heading home to her daughter. She never reported it. The second time, a couple of years later, a former boyfriend broke into her house while she was gone. When she got back home, he brutally beat her and raped her. This time, she reported it but she ended up with a pending domestic violence charge; he was let go.

She finally ended up telling her father what happened right before she went to prison. "I was ashamed. I felt like it was my fault. It would never have happened if I were to just stay at home with my child. So, I I turned that on myself and that was probably the day that changed me for a very long time." She started using again.

When Ruble went to ORW, she kept in contact with her daughter through letters and phone calls. Her mother brought her daughter for visits, and they remained very close. Her daughter is now in middle school, and Ruble says they are closer than ever. She said the Tapestry program made her take a look at herself — she realized she wasn't a bad person. She had made some mistakes but wanted to change.

"I don't have to like or love anyone that treats me as if I'm worth nothing. Or will never be anything. It's just, and I don't know, it was just the best thing that ever happened to me," Ruble says of Tapestry. Ruble now works for a community nonprofit on a rapid response team that intervenes when people overdose. She gives people Narcan to prevent future overdoses and offers counseling. She said before the rapid response team in Lima was set up, there would be as many as eight deaths a week. Ruble says that number has lowered a little, but not by much. There have been more drug busts and more education but she still sees a lot of people who are using.

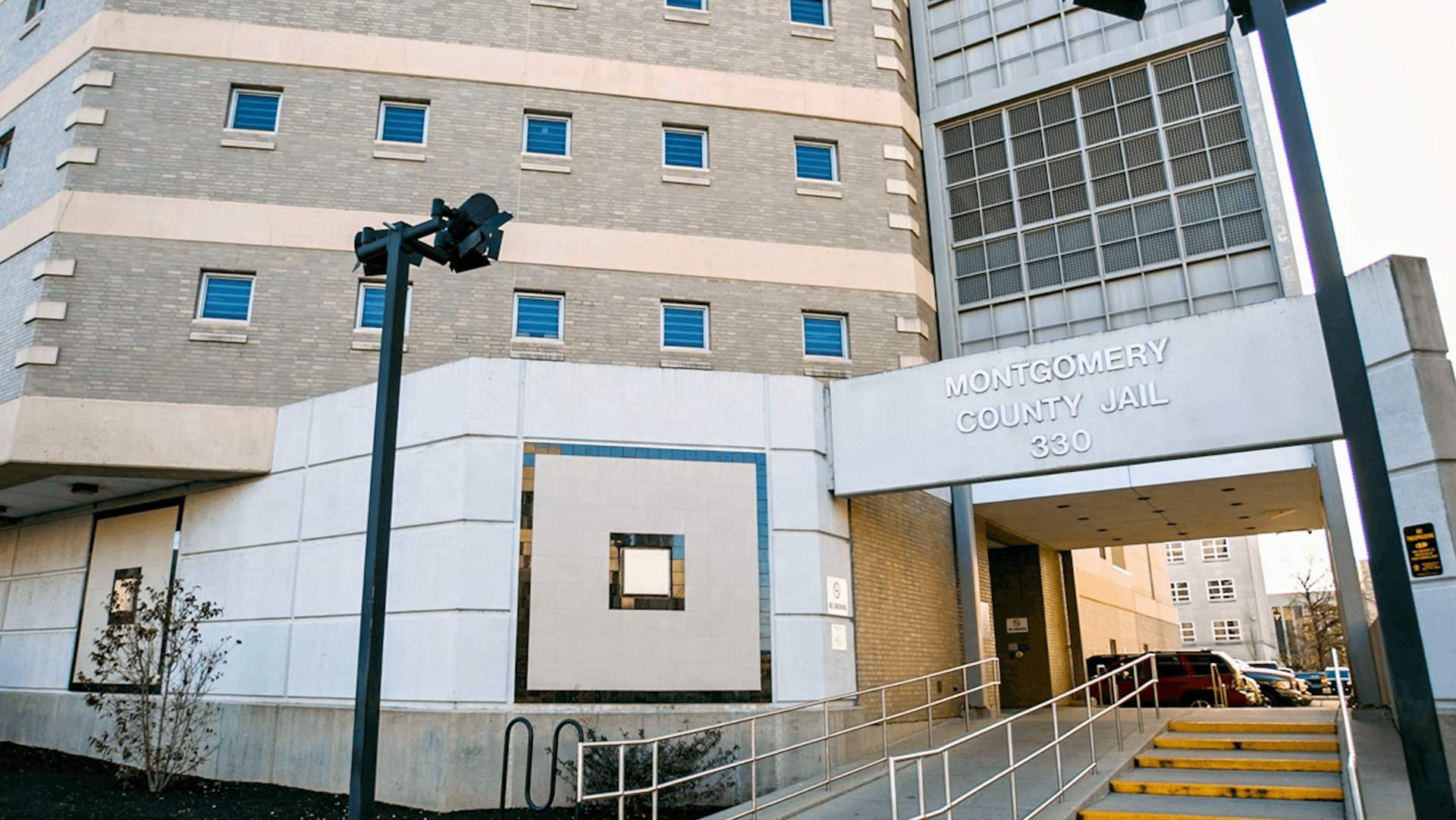

Montgomery County Jail, about an hour southwest of ORW, has a social worker on staff who helps find housing for those in need and can work with women who want to enter into a treatment program. That's a change from a few years ago — when the jail had no social worker and fewer programs.

Maj. Matt Haines has been with the Montgomery County Sheriff's Office for 13 years and was on the police force before that and says he hasn't seen anything like this recent spike in women in his jail. He says they've had to reorganize the different "pods" or rooms where the women live because they've run out of beds.

One thing is clear with the women here: They didn’t wake up one day and decide to be addicted to drugs. It just spiraled. A woman we'll call Janet (we can't use her real name because the jail did not give us permission) testifies to that: “I was taking pain medication for my foot and that’s where opiates escalated. And then they become too expensive on the streets. You start using heroin. It’s cheaper. It’s easier to get," she says.

She is one of 174 women awaiting a court hearing in Montgomery County and seeing what treatment options will be offered to her before she gets released. She says she's "done" with using, like a lot of other women I meet here. The problem is, many of the women will go back to the same neighborhoods where they were using and be around the same people they were using with. The Montgomery County Sheriff's Office and the drug court gives them treatment options, of which there are a few that treat just women.

Haines wants to find ways to keep people out of jail.That seems to be the opposite of President Donald Trump's recent get-tough statements about drugs — he recognizes opioid addiction as a major epidemic but has called for harsher penalties for those dealing and trafficking, including capital punishment. But Haines says, “We cannot arrest our way out of this problem. These women need help, and we are not equipped here at the Montgomery County jail to treat this disease. We keep seeing the same person and the behavior that causes the addiction is still there."

“When you're talking with a with a person that's experiencing addiction, you see it's not an 'addict.' And I really cannot stand that term because it takes the human being out of this whole disease and this illness. It's the same thing as having a chronic health care illness," says Emily Surico, who works at East End Community Services, an organization that's been in the Twin Towers neighborhood of Dayton since 1998. Twin Towers has been hit hard in the opioid epidemic. Her organization works closely with the Dayton Police Department to offer treatment and support to women before and after they are incarcerated. Surico says Dayton Police led the way in curbing overdose deaths. In 2016, Montgomery County had more than 800 deaths due to overdoses. In 2017, it was just over 500. A small step, she says, but a good one.

It’s not the be-all and end-all. Surico and others in the community working to address these problems recognize that addiction isn't something you can solve overnight. Another thing they agree on: You can’t just arrest your way out of this problem. For a lot of these women, they just need another chance.