Playing Against the Virus

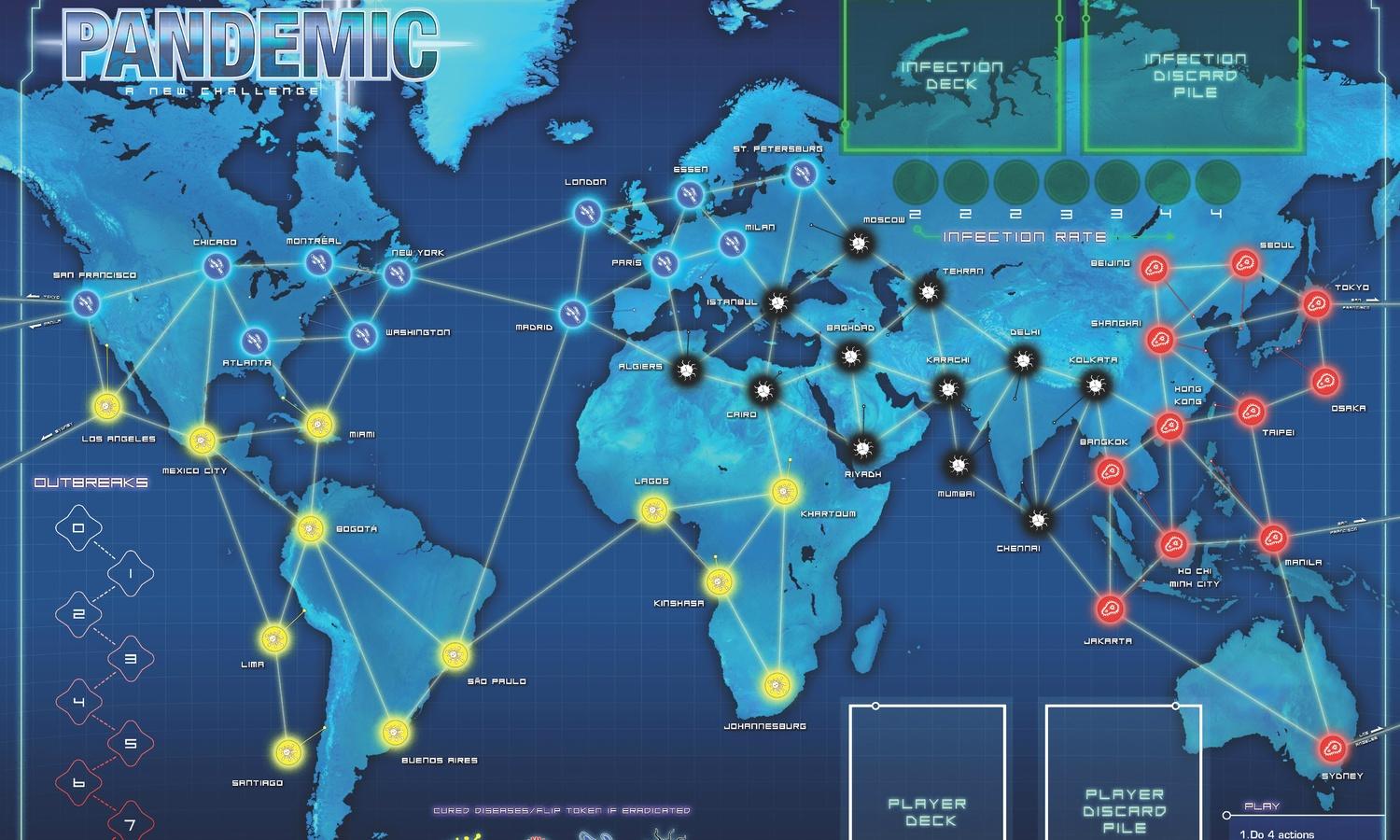

The game board of “Pandemic”

Lately, viruses have been spreading through the gaming world. In the online game“Pandemic 2,” you play the virus, aiming to wipe out humanity. In“The Great Flu,” you control an international health organization and make decisions about face masks and airport closures.

Reporter Michael May tried out the board game“Pandemic.” It’s a cooperative game, meaning that everyone is on the same side, moving resources around the board to contain an outbreak that threatens to overwhelm the world. “Diseases seemed a natural opponent for a group of players to fight against,” says the game’s designer,Matt Leacock. “They’re inhuman, cold, hard to identify with, mysterious, they can grow out of control.” Players can use their turns saving infected cities one by one, but they’ll quickly find that that strategy won’t save the world — you have to use precious moves to work with the other players to discover a cure. “There are some very difficult trade-offs to be made,” says Leacock. “At least you can all agree you are trying to save world, even if you’re letting certain cities fall into chaos.”

Games like”Pandemic“are designed to teach good public health. But for one epidemiologist, the real lessons come from an outbreak that occurred several years ago in“World of Warcraft,” the massive multiplayer game. Avatars started mysteriously dying en masse. “It was a fantastic outbreak,” says the researcherNina Feffermanof Rutgers University. “People exploded into a cloud of blood with a littlepffftsound. It was really awesome.”

The epidemic was “real” in the sense that it was unintended. A spell created by the game’s developers got out of control when stronger players who survived it carried the spell with them into population centers, where weaker players caught it. Fefferman and her team analyzed the responses of players, who had a genuine investment in their avatars, to model what might happen in a real-world outbreak. “Good science happens in strange places,” she says. One thing they hadn’t modeled was curiosity, “people putting themselves at risk to get a better and cleaner understanding. We had thought of quarantine — draw a big circle and nobody leaves. But we hadn’t thought of things like journalism, which enables public oversight of otherwise closed activities. That’s something we never would have thought of without looking at this scenario inside’World of Warcraft.'” They published their findings inThe Lancet.

These and other virus games have one thing in common: players are forced to think strategically about how to deal with a situation that is escalating out of control, a skill known as systems thinking. “A lot of people think about systems thinking as a new 21st-century skill,” says game designer and professorMary Flanagan, who created the vaccination game “Pox.” “It’s not that well understood how to teach systems thinking. When faced with a complex problem, how do we break that down, and try to understand the situation?”