The (New) Last Supper

There’s a new art installation on Manhattan’s Upper East Side that’s creating quite a stir. It opened just last weekend, but already, it’s commanding attention for its dramatic, novel use of light and sound. You may have heard of the artist: Leonardo da Vinci.Sort of.

The artwork in question is a kind of collaboration across the centuries, between da Vinci and British film director Peter Greenaway. Greenaway — best known for 1989’s controversial ‘The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover’ — applies his expertise with film techniques and technology to a 45-minute treatment of da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

- Greenaway wants viewers to “retrain their gaze,” so they can experience classical paintings with the same immediacy as the original Quattrocento audiences. Writing about 50 years after da Vinci completed the painting, artist Giorgio Vasari described it as “wondrous” in its depiction of confused, suspicious, and sorrowful Apostles trying to figure out who would betray Jesus. Da Vinci was a master of realism; he reproduced lifelike images in paintings that took years to create. It’s a skill that doesn’t have quite the same effect on today’s viewers, many of whom can experience, reproduce, and alter just about anything at which they can point a camera phone.

The resulting loss is doubly-felt. Modern viewers, no longer awed by the technical brilliance of da Vinci’s work, also miss its deeper meanings. If the gaze isn’t held by a painting’s forms, the mind won’t linger long enough to engage them. It’s an abandoned state of mind that Greenaway seeks to recreate. The director wants to rediscover The Last Supper’s “multiple layers of meaning, the techniques used and the metaphors intended.” He wants to “investigate and educate but also to fascinate and celebrate these extraordinary complex images.”

So how do you overcome 500 years of distance between viewer and painting? Greenaway adopts the language to which modern audiences are accustomed — and with which he is most comfortable. He inserts the busy, rapid, loud, and sometimes bombastic visual language of film into the painting. Through a succession of projected images and music he forces viewers to reread the painting’s details and composition.

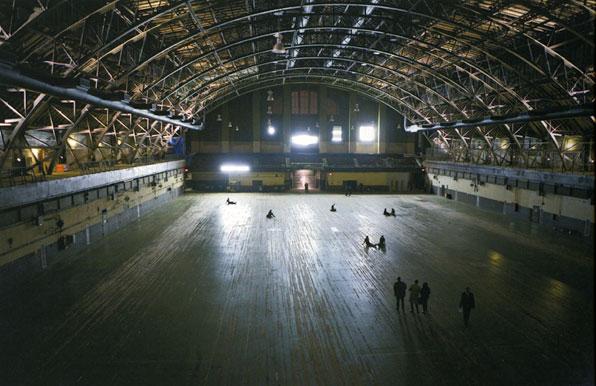

Greenaway takes over the expansive 55,000-square-foot drill hall in New York City’s Park Avenue Armory, dividing it into two spaces. Viewers enter the first space and are flooded with images and music from the past five centuries of Western culture. The projection of a male ballet dancer leaps around them, evoking, then giving way to da Vinci’s Vetruvian Man. Verdi meets Bach. Present-day Rome mingles with Masaccio. It’s a modern “mash-up” of five centuries of art, music, and architecture. The effect is at once disorienting and somewhat clich, evoking a giant, overwrought introduction to some generic PBS special on Italian art.

After the commotion of the first room, the audience is invited to enter the calm of a second viewing room, housing an exact reproduction — the company that produced it calls it a “clone” — of The Last Supper. It is here that Greenaway really draws from his bag of cinematic tricks. He “animates” the painting, manipulating light and projecting digital images onto it. The Apostles’ hands appear by themselves, accentuating the expressiveness of their gestures. Then the knife in Peter’s hand is spotlighted. Birds — a fascination of da Vinci’s — flutter through the painting. Bright colors fade to grey, and then surge back to their former brilliance. These constant shifts in lighting invest Jesus and the Apostles with density and weight, drawing them out of the painting and into the Armory. At times they seem almost real — if not alive, then present in a tangible, sculpted form.

Greenaway’s effects illuminate the reproduced painting.

The installation is part of the director’s ongoing series Ten Classical Paintings Revisited — and it’s a series with a purpose. The Wall Street Journal calls it “an appeal to youth who are lacking an education in the art of the past,” those who in Greenaway’s words “think there is no painting before Pollack and no film before Tarantino.” The appeal to youth and to modern audiences is clear. With all the bells and whistles of a 21st century motion picture, Greenaway isn’t trying to reproduce the same relationship a renaissance viewer would have had with The Last Supper…but he does provide an entertaining way to understand it.

-Michael Guerriero