Cartoonist Ramón Esono Ebalé finally released from jail in Equatorial Guinea

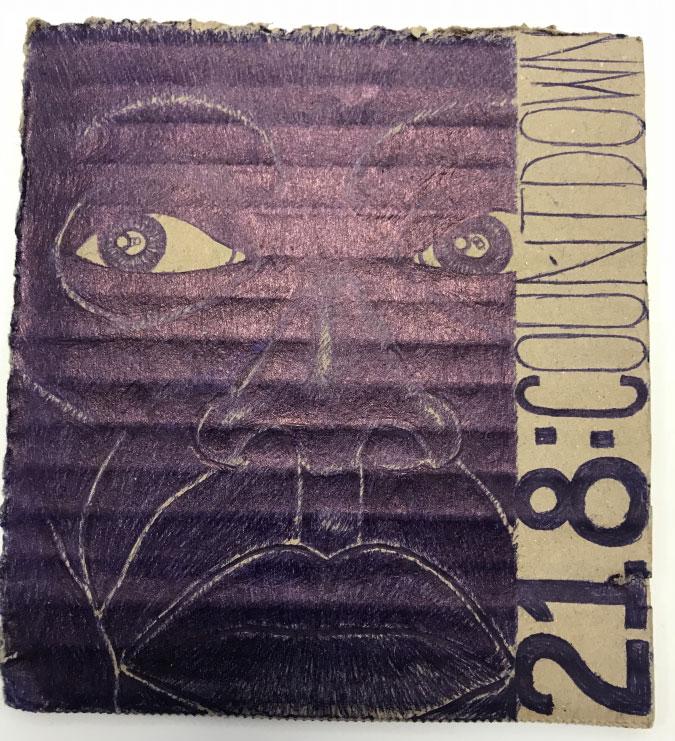

Equatorial Guinean illustrator and comics artist Ramón Esono Ebalé looks on in court in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, on Feb. 27, 2018. The prosecutor of Equatorial Guinea dropped all charges against Ebalé because of 'lack of evidence.'

Editor's note: Cartoonist and blogger Ramón Esono Ebalé was released from prison on March 8 after serving more than five months in jail in Malabo. Ebalé, who has lived outside of Equatorial Guinea since 2011, was arrested and charged with money laundering and counterfeiting last September while on a trip home to renew his passport. He was aquitted on Feb. 27 after a policeman, the state's main witness, recanted his story under cross-examination and said he was only following orders when he accused Ebalé of criminal activity.

“Ramón’s release from prison is a testament of the power of collective work of dozens of organizations, hundreds of artists and concerned citizens,” said Tutu Alicante, director of EG Justice, which promotes human rights in Equatorial Guinea. “But we must not forget that dozens of government opponents who are not as fortunate fill Equatorial Guinea’s jails, and that the fight against human rights violations and impunity needs to continue.”

Read the complete statements by Human Rights Watch and the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Tiny Equatorial Guinea may have a sense of humor after all.

On Feb. 27, the country's public prosecutor dropped all charges against cartoonist Ramón Esono Ebalé and demanded his release for "lack of evidence." Ebalé was jailed five months ago while visiting his home country to renew his passport.

"From the time that Ramón was detained, we all knew that the charges brought against him were completely made up," says Tutu Alicante, a friend of Ebalé's and the head of EG Justice, a human rights group focused on Equatorial Guinea. He says the real reason was Ebalé's cartoons.

Amnesty International's account of Ebalé's arrest confirms that. The cartoonist was leaving a restaurant in Malabo on Sept. 16, 2017, when state security agents arrested him and two friends, both Spanish nationals. The three were handcuffed and their mobile phones confiscated. They then were taken to the Office Against Terrorism and Dangerous Activities, where Ebalé was questioned about his cartoons. The Spanish nationals were released the same day.

"It was clear from the very beginning that Ramón was being targeted for speaking out," Alicante says, "for using his art and his blog to criticize the excesses of a government that has been in power longer than any other government we can point at."

The president of Equatorial Guinea, Teodoro Obiang, took power in a coup in 1979. He's now the longest-serving leader in Africa.

Ebalé, officially charged with money laundering and counterfeiting, has been held in Equatorial Guinea's infamous Black Beach prison since last September. After his arrest, direct appeals to President Obiang to release Ebalé went unheeded. Then in November 2017, Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI) awarded Ebalé its Courage in Cartooning Award. The next month, CRNI and an international legal team filed urgent appeals to the United Nations demanding Ebalé's immediate and unconditional release.

Alicante says now that the charges against Ebalé have been dropped, it shows that even in Equatorial Guinea, pressure from human rights groups, the international community, artists and activists can have an affect.

"We are relieved to see that at least in this case some sense of justice can be claimed here," Alicante says.

But there's one problem: Ramón Esono Ebalé is still in prison.

Alicante says he expects to hear of Ebalé's release date any day now, but so far, there has been no word.

"I think the judicial authorities have no choice but to acquit him of charges and let him go free," he says. "However, the experience of almost 40 years of dictatorship in Equatorial Guinea tells me we cannot be confident, we cannot celebrate until Ramón is, in fact, home with his family."

Equatorial Guinea is a tiny county. Part mainland and part island (where the capital, Malabo, is located), the West African nation has a population of under one million, most of whom live in dire poverty. The same family has ruled Equatorial Guinea since its independence from Spain in 1968. Offshore oil was discovered in the mid-90s, and wealth started to pour into the country, but it is not shared among all residents.

Visitors say there's now several blocks of visible oil wealth in Malabo. Human Rights Watch describes an Equatorial Guinea where few share opportunity: "Corruption, poverty, and repression continue … Vast oil revenues fund lavish lifestyles for the small elite surrounding the president, while a large proportion of the population continues to live in poverty. Mismanagement of public funds and credible allegations of high-level corruption persist, as do other serious abuses, including torture, arbitrary detention and unfair trials."

Human rights lawyer Alicante says what's important to understand is that despite Equatorial Guinea's deplorable reputation, the government has an outsized role in international affairs. "We're talking about a government that now sits on the UN Security Council. This is a country that is also a chair of the African Union and one that holds important international conferences in the country."

Equatorial Guinea restricts freedom of expression, especially anything critical of the government. This is one of the reasons Ebalé left in 2011. But his cartoons managed to reach his home country via the Internet, and copies were smuggled in and distributed by hand.

"Internet penetrability in Equatorial Guinea is very low," Alicante says. "However, people are able to find creative ways — going to cyber cafes, or going to their offices at oil companies and government offices — to download the blogs and images that Ramón was creating."

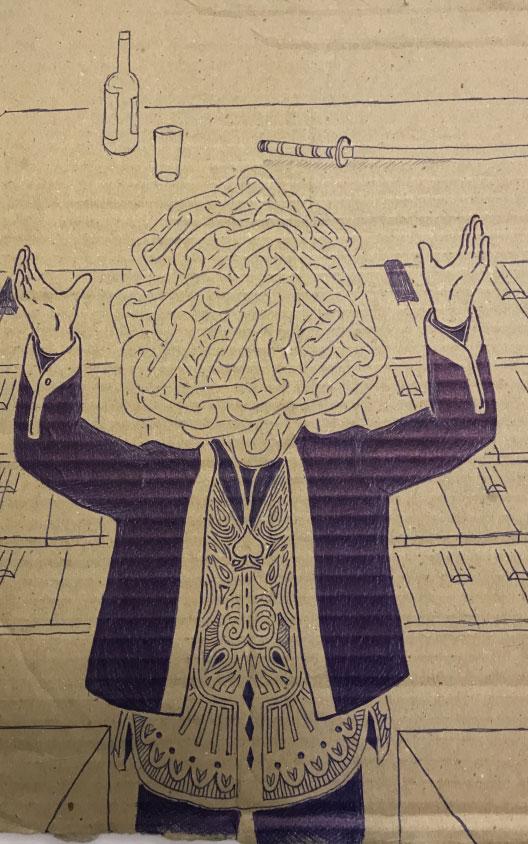

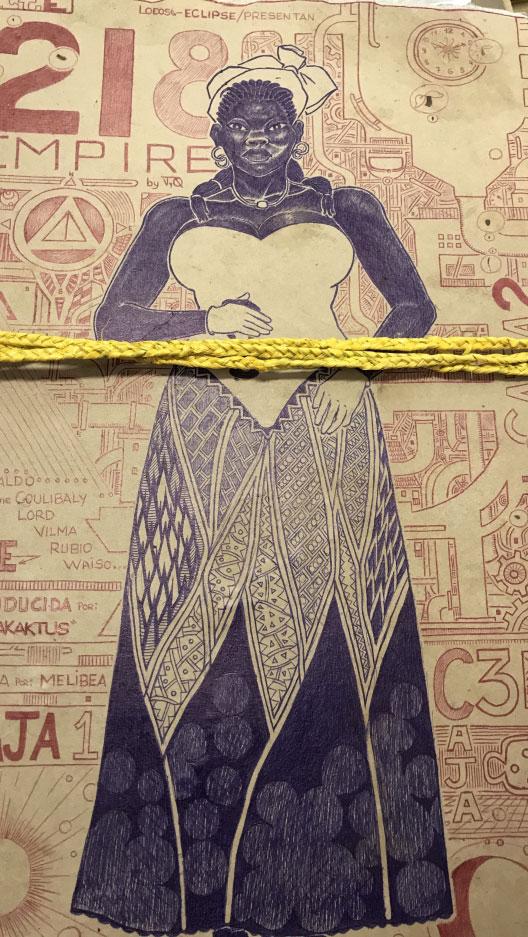

One of them is an especially biting graphic novel by Ebalé called "Obi's Nightmare."

Tutu says "Obi's Nightmare" poses a simple question: What would be the worst possible fate to befall President Obiang? The answer: spend a single day as an ordinary citizen of his own country.

"The graphic novel shows the corruption, the crime, the excesses of this government that has been in place now for 39 years," Alicante says. "And that is something that President Obiang is not going to admit."

But Alicante says there was something more to "Obi's Nightmare."

"[Ebalé's] idea behind this novel was to have citizens laugh and lose their fear of Obiang, who many people see as God inside the country. And that kind of poking fun at someone who sees himself as all-powerful is a kind of criticism, a type of freedom of expression that Equatorial Guinea and President Obiang, in this case, does not permit."

In the case of Ebalé, Equatorial Guinea's own court has vindicated him and forced the government to tolerate being made fun of. But until the cartoonist is released, Alicante will not rest easy.

"While Ramón remains in the country, he remains in a huge prison, which is Equatorial Guinea."