China bans airtime for ‘artists with tattoos, hip-hop music’

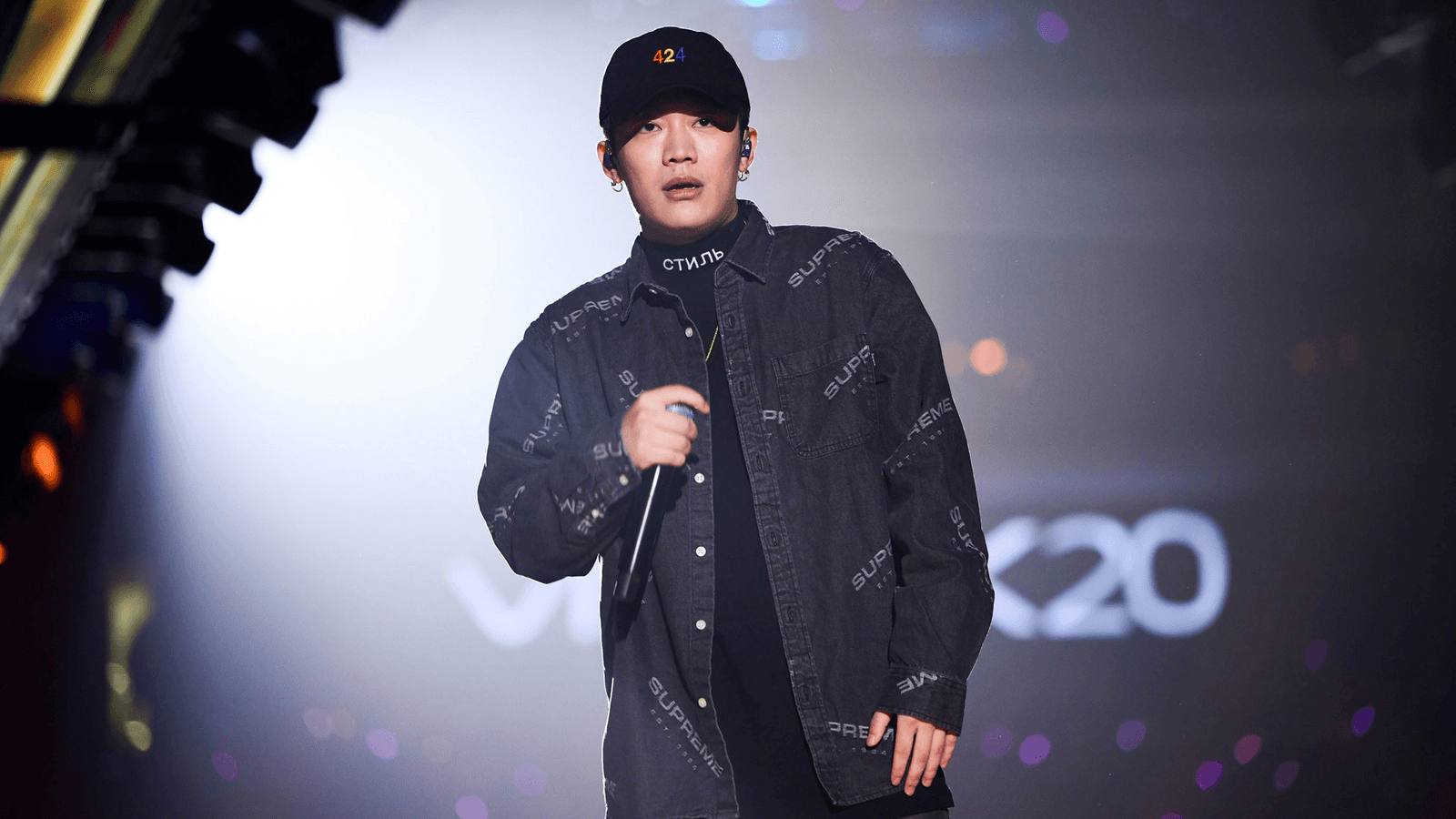

Chinese rap singer Wang Hao, better known by his stage name PG One, performs during a New Year concert in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China, Jan. 1, 2018.

Chinese rap and hip-hop seemed poised to break out after a wildly popular singing show brought mainstream legitimacy to a musical style that had struggled to find its voice in China.

But an abrupt official backlash against hip-hop culture has tamed the swagger of artists who fear that Chinese rap's development, like a once-promising homegrown rock-and-roll movement, will be nipped in the bud by Communist politics.

"I don't need to be such a superstar — it's very dangerous," Shanghai rapper Mr Trouble said of the sudden shift in climate.

He is now back in the studio, watering down a new album to avoid blowback.

"You gotta be a smart person. Even though it's soft and weak, it's a hip-hop album. I put my attitude in it. If you are smart too, you can dig it out," said Mr Trouble — 28-year-old Hong Tianlin.

The past year has given Chinese rappers a case of whiplash.

China lacks the racial issues and "gangsta" street culture that made rap and hip-hop social and cultural forces in America.

But it slowly took root as artists infused beats with commentary on issues like China's growing economic inequalities, adding in ancient Chinese philosophical references, and often rapped in earthy local dialects.

Then came the smash-hit "The Rap of China."

Debuting last summer, the internet-based rapping contest became one of China's most-watched programmes, thrusting rap onto the national stage and earning its stars fame and recording contracts.

More money, more girls

Chen Wei, the show's producer, told state media last July that Chinese hip-hop was "on the threshold of becoming really big and mainstream".

The benefits trickled down to the likes of Mr Trouble, a chain-smoking self-taught musician and record producer.

"Even if we didn't like that show, it influenced us a lot. We earned more money, and more girls love us," he said, chuckling.

But rap's brief spring seemed destined to end under President Xi Jinping, whose government has tightened the screws on anything considered antithetical to the ruling Communist Party's values.

In August, the artist "Fat Shady" raised eyebrows with a profane rap against foreigners.

And last month, PG One, co-winner of "The Rap of China", came under fire over a 2015 track containing sexual and drug references, and a rumored fling with a married actress.

Finally, in mid-January a leaked government directive banned airtime for "artists with tattoos, hip-hop music" and other content that "conflicts" with party morals.

A second season of "The Rap of China" is now in doubt, and artists say music venues won't book rap acts.

Li Dalong, chief operating officer of Mao Livehouse, which has eight venues across China, said hip-hop artists now face "more careful screening" for "ideological mistakes" in their music.

"The biggest difficulty facing rappers is that sponsors are fleeing. I don't even know if 'Rap of China' season two will be allowed," he told AFP.

Unlikely to 'shut up'

In the 1990s, Chinese rock was similarly poised for a breakthrough as rockers tapped into angst about rapid socio-economic change.

But the government soon banned it from television and restricted live performances, forcing it back underground.

Some fear the same for hip-hop, or worse — being co-opted by the party.

Groups like CD Rev from the southwestern city of Chengdu sing patriotic rap, working with the Communist Youth League to release songs like "This is China".

The track hits several Communist talking points like improving food safety and protecting China's sovereignty, with lyrics like "The red dragon ain't no evil but a peaceful place." It went viral on its release in 2016.

Purists call it propaganda, but group member Pissy — Li Yijie — says it's about "positive energy."

"Rap and hip-hop have to express our ideas. We are expressing our own ideas instead of pursuing edgy music," the 24-year-old said, adding that CD Rev also expects to lose some business under the crackdown.

For edgier artists like Shanghai's Naggy, the future is unclear.

"We've gotta find a way. But we don't want to have to 'find a way' to express ourselves. We just want to express ourselves," he said.

Shzr Ee Tan, an ethnomusicologist at Royal Holloway University of London, said hip-hoppers won't "simply shut up."

"What could get interesting is how they react to the ban, creatively and socio-politically. Do they dig in deeper into their perceived non-mainstream positions?" she said.

"I suspect quite a few artists will actually choose to work with the government … as rockers have done."

The ban encompasses China's broader "sang" subculture, a catch-all for youthful pessimism.

But it also hurts Mr Trouble, whose raps touch on romance, his beloved parents, and his Shanghai childhood.

Despite his bad-boy nickname, he says China's government "is doing well" at managing the huge country.

But he's tempering his dreams.

"We still got fans, and we still see hope. But even if hip hop is dead in China, I will still make rap songs. I will record them and sing to myself."

Dan Martin of AFP reported from Shanghai.