Actions, not words, tell Trump’s political money story

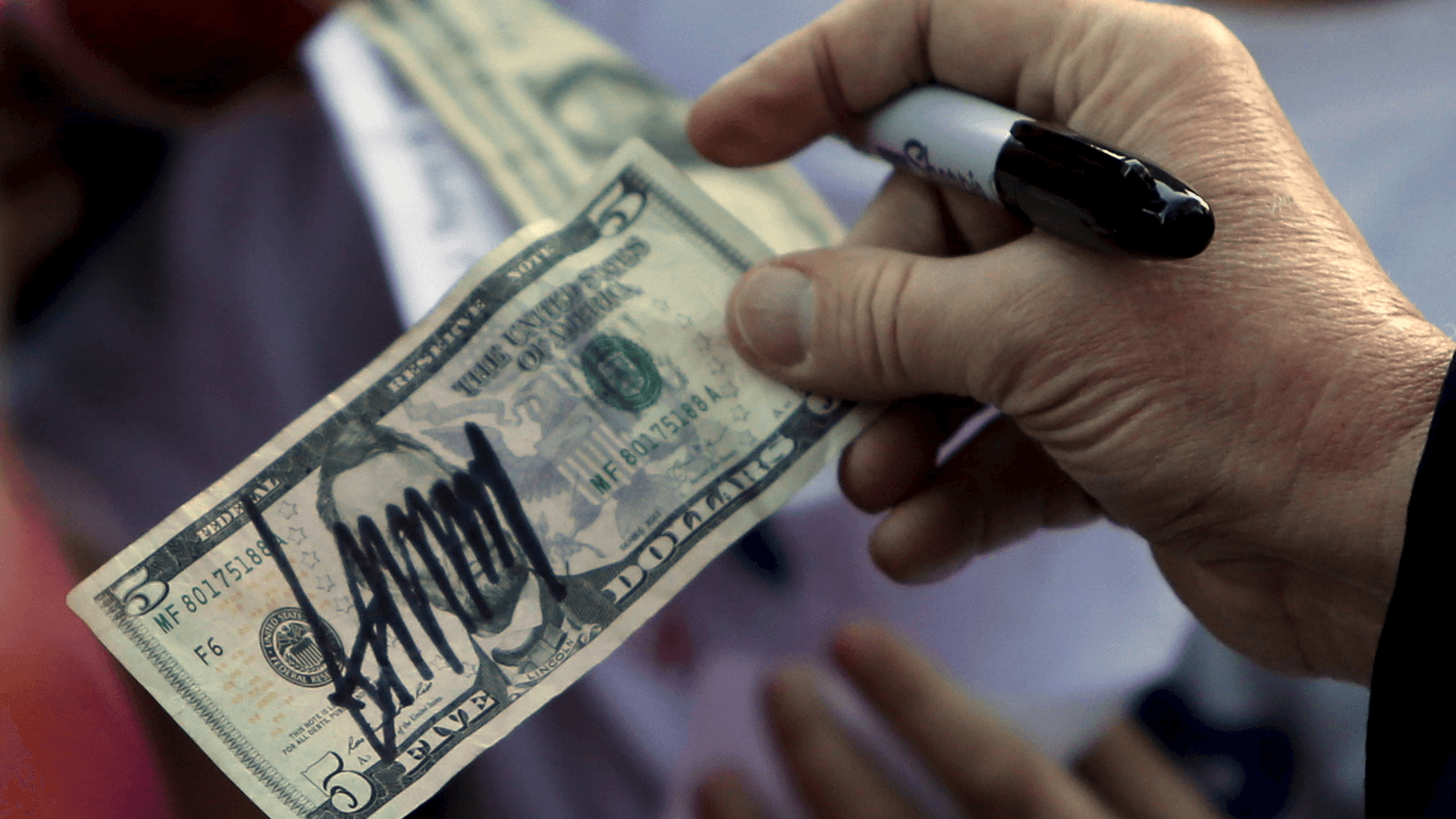

Donald Trump hands a five-dollar bill back to a supporter after signing it for her following a rally with sportsmen in Walterboro, South Carolina, Feb. 17, 2016.

Donald Trump made his first and most definitive statement about campaign cash just moments after announcing his intention to run for president.

It’s the one that stuck in everyone’s mind.

"I don’t need anybody’s money. It’s nice. I don’t need anybody’s money,” Trump said on June 16, 2015. “I’m using my own money. I’m not using the lobbyists. I’m not using donors. I don’t care. I’m really rich.”

Over subsequent months, Trump would double and triple down on his seemingly reformist rhetoric that mocked Republican orthodoxy.

He criticized the Supreme Court’s money gusher of a decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

He cold-shouldered the billionaire Koch brothers and Republican megadonor Sheldon Adelson.

He blasted big-money super PACs as “unfair,” “horrible,” “scams” and in violation of both the spirit and letter of federal election law. Politicians who rely on such super PACs are beholden to their wealthy contributors, Trump declared.

He then vowed: “That’s not going to happen with me.”

Trump on Saturday marks the one-year anniversary of his presidential inauguration. It coincides with the 8th anniversary of the Citizens United v. FEC decision, which allowed corporations, unions and certain nonprofits to raise and spend unlimited amounts of money to advocate for and against political candidates.

Do Trump’s stage-setting declarations about political money still carry currency as he begins his second year in office? Do his statements hold as he begins marshaling resources aimed at winning a second term?

The White House did not respond to requests for comment. But the answers seem clear nevertheless. For the most part, Trump’s actions have betrayed the promises that he uttered at the outset of his presidential journey that now seems so very long ago.

‘I don’t need anybody’s money’

Theoretically, this statement is true. In practice, it’s not.

As 2015 bled into 2016 and Trump solidified his standing atop the Republican presidential field, his campaign began soliciting contributions ahead of a general election showdown with Democrat Hillary Clinton and her massive political fundraising machine. In all, Trump would raise about $339 million.

And while Trump’s campaign initially disavowed super PACs purporting to support Trump — especially those incorporating Trump’s name or “Make America Great Again” sloganeering — that pushback evaporated as Election Day crept closer. Super PACs and politically active nonprofits ultimately bolstered Trump with tens of millions of dollars in fresh support.

And Trump’s pursuit of contributions for his 2020 re-election campaign began soon after he won the presidency.

He filed paperwork forming his re-election campaign on the day of his inauguration. During the first three months of 2017, Trump 2020 raised $7.1 million, much of it from small-dollar donors responding to an endless stream of emails, text messages and social media solicitations targeting Trump’s core supporters.

By Sept. 30, Trump had raised nearly $36.5 million from donors toward his re-election effort, according to federal filings. That figure is likely to jump by tens of millions of dollars come Jan. 31, the date by which Trump’s re-election campaign must reveal its finances for all of 2017.

If Trump didn’t need this money, he could simply stop raising it.

Instead, he’s pursuing other people’s cash as aggressively as ever since becoming president, culminating this month with a campaign sweepstakes to win dinner with him in Florida at his Mar-a-Lago resort.

A pair of pro-Trump super PACs, meanwhile, crossed the $1 million threshold of spending in support of Trump’s re-election in just the first quarter of the year.

‘I’m using my own money’

Trump has demonstrated no willingness — neither during the 2016 presidential campaign nor since — to single-handedly bankroll his political affairs.

Make no mistake: Trump did use $66.1 million of his personal fortune to fuel that 2016 presidential campaign. Few political candidates have such means.

But the self-funding represents less than one-fifth of the more than $333 million his campaign raised from all sources, including individual donors, party committees and political action committees.

And the president so far hasn’t donated a dime to his re-election efforts, which include staging campaign-style rallies across the country and otherwise promoting himself.

Trump’s actions are proof he’s “misled the American people and is lying about his intention to ‘drain the swamp’ and rid DC of corruption,” argued Karen Hobert Flynn, president of Common Cause, which advocates for campaign money restrictions.

Not so, says attorney Jim Bopp, who has fought against political money limits in some of the nation’s most notable court cases, including Citizens United v. FEC.

“Liberals refuse to understand with Trump that you can’t take what he says literally,” Bopp said. “What is important about Trump is what he’s doing and not what he’s saying, and in practice, everything he’s done is in step with maintaining a 1st Amendment-friendly approach to campaign finance.”

‘I’m not using the lobbyists’

Trump tongue-lashes lobbyists. He’s placed some limits on his administration’s staffers’ ability to one day work as lobbyists.

But Trump appears to like lobbyist money just fine — and the lobbyists who help him raise that cash.

While the money his 2016 presidential quest raised from registered lobbyists was modest — significantly less than the hundreds of thousands Clinton’s campaign raised from K Street — Trump appointed professional lobbyists to key fundraising positions within his campaign.

Most notable: lobbyist Brian Ballard, a top fundraiser for Trump’s campaign who also personally donated $5,400 to Trump’s campaign.

Career lobbyist Paul Manafort served a stint as Trump’s campaign chairman and returned to lobbying the federal government last year even as investigators probed his past government relations work on behalf of foreign clients. Special counsel Robert Mueller III has since charged Manafort in a case that involves his lobbying for pro-Russian politicians in Ukraine.

Trump’s presidential transition committee, meanwhile, accepted tens of thousands of dollars from federally registered lobbyists despite statements from spokesman Jason Miller that the panel was “not going to have any lobbyists involved with the transition efforts. … When we talk about draining the swamp, this is one of the first steps.” Transitions are funded with a combination of public and private money.

Among the interests represented by these lobbyists: Coca-Cola, Comcast, Pfizer, United Airlines, Visa, AT&T, Newsmax Media, Lockheed Martin, Philip Morris International, the US Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform and private prison company GEO Group.

Several lobbyists also spent some time working for the Trump transition.

Trump patently banned contributions to his inauguration efforts from people registered as federal lobbyists. But he accepted huge donations from corporations, such as those in the energy industry, that spend millions of dollars on federal lobbyists and have pressed the Trump administration for favorable treatment.

Also anteing up: ultra-wealthy individuals who aren’t lobbyists by profession, but nevertheless petition the government — among them casino magnate Adelson, who Trump had previously derided — to smile upon their pet issues and business interests.

Last year, Trump named both current and former lobbyists to his administration. He’s also named lobbyists to commissions and other positions, including Richard Hohlt, who’s earned hundreds of thousands of dollars from the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

‘I’m not using donors’

Trump most certainly has used donors. Lots and lots of them.

A Center for Public Integrity analysis of Trump campaign filings with the FEC, coupled with a February study from the nonpartisan Campaign Finance Institute, conservatively places the number of donors to his campaign in the low seven figures.

Determining an exact number of Trump givers isn’t possible, as federal political candidates are not required by law to reveal the identities or exact contribution amounts of donors who give a campaign $200 or less. Trump, like most political candidates, doesn’t volunteer this information.

Because of that, in all likelihood, Trump’s number of donors is much higher, as legions of Trump backers pumped Trump’s presidential effort with small-dollar offerings — $10 here, $50 there.

Many tens of thousands more gave Trump’s campaign more than $200. And donors continue to support his re-election committee in similar fashion: This year, Trump’s campaign has collected millions of dollars’ worth of individual contributions, federal records show.

Trump also is benefiting from the many donors who’ve helped fund a gaggle of super PACs that support him.

Despite Trump’s stated distaste for super PACs early on, which included sending the FEC letters disavowing some of them, Trump eventually accepted their support.

Among the billionaire backers who have supported those super PACs since Trump kicked off his campaign: Robert Mercer and his daughter, Rebekah Mercer, who have been critical to Trump’s political ascendance, and not just with cash. When Trump’s 2016 campaign hit the skids weeks before Election Day, it was with the Mercers’ guidance that Trump brought advisers Steve Bannon and Kellyanne Conway aboard in leadership positions.

Future45, among the richest pro-Trump super PACs during Trump’s presidential bid, was largely bankrolled by Adelson and his wife, Miriam Adelson. Other seven-figure donors to Future45 include Linda McMahon, who Trump would later appoint as head of the Small Business Administration, and Joe Ricketts, founder of TD Ameritrade.

Today, more than a dozen super PACs and similarly pro-Trump political nonprofits are actively advocating on Trump’s behalf. With an eye toward Election Day 2020 nearly three years away, pro-Trump super PACs have already raised millions of dollars in recent months.

Ted Harvey, a former Colorado state senator who leads the pro-Trump Committee to Defend the President super PAC, which had a $1.35 million cash reserve as of its last disclosure in June, says Trump changing his mind on super PACs makes perfect sense.

Prior to his election, Harvey said, Trump’s primary exposure to super PACs involved “globalist megadonors who flushed $100 million down the toilet” in support of “faux conservative” Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush, Florida’s former governor.

“Their relentless efforts to stop the populist Trump revolution would cause anyone to question the corrupt Washington, DC political process,” he said. “However, after enjoining the support of tens of thousands of everyday Americans who have come together as members of the Committee to Defend the President, it is not surprising Trump’s position on super PACs has evolved.”

‘I don’t care’

In reality, Trump’s dozens of messages to prospective donors since his inauguration suggest that he cares deeply about fundraising. Sometimes, he even explicitly says he cares about their financial support.

“You are the lifeblood of this movement, and that’s all I care about,” Trump wrote to prospective donors on Dec. 16. After Christmas, Trump assured potential backers that he cares about their dollars in whatever amount. “It is the fact that you PROVED you care about this cause so much that you actually stepped up and made a contribution. That is why we won, and why we will keep winning,” Trump wrote.

In contrast, Trump’s actions suggest he cares little for campaign finance legislation and political money administration.

While he frequently employs the “drain the swamp” catchphrase as a battle cry against Washington corruption, Trumpian swamp-draining has not yet involved supporting efforts to blunt Citizens United v. FEC, squelching super PACs and their moneyed donors or otherwise restricting campaign fundraising.

Trump has made no moves to back various bills — most sponsored by Democrats, none of which have much chance of passing — to alter the nation’s campaign funding system.

Nor has Trump paid heed to some Republicans’ attempts to boost or altogether abolish the current $2,700 per candidate, per election federal contribution limit.

Such a move, supporters argue, would allow candidates’ own committees to control more money and thereby reduce the influence of super PACs, which candidates are barred by law from personally controlling.

At the FEC, which is led by six presidentially appointed commissioners, five of those commissioner slots are filled by people whose terms expired years ago. The sixth slot has been vacant since March, when Democrat Ann Ravel resigned.

Trump has nominated one person — Texas lawyer Trey Trainor — to fill the spot currently occupied by Republican Matthew Petersen. Trump last year nominated Petersen to serve as a US District Court judge, but Petersen withdrew in December after a disastrous hearing before the Senate. Petersen remains on the commission and Trainor lingers in limbo — he has yet to receive a confirmation hearing from the Senate.

Trump’s White House Counsel is Don McGahn, a former FEC chairman and arguably the most outspoken opponent of campaign finance regulations to ever serve at the agency.

“There was no reason to believe that Trump’s reform rhetoric would meet up with reality, and it didn’t,” said Karl Sandstrom, senior counsel as law firm Perkins Coie and a former Democratic FEC commissioner.

‘I’m really rich’

Fact check: true.

This story is from the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative media organization in Washington, DC. Read more of its investigations on the influence of money in politics or follow it on Twitter.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?