Maria Geneva Reyes talks to grants management coordinator Betty Wong at their Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach office in downtown San Francisco on Dec. 15, 2017. She works there full time while taking a full course load at a local community college.

Until recently, Maria Geneva Reyes’s plan seemed pretty straightforward. She would finish her last semester at Skyline College in San Bruno, California, and transfer this fall to a California State University campus to work on a bachelor’s degree in communications.

Earning a degree has long been a dream of hers — and it was her father’s wish, too, for her and her three brothers. The chance at a better education was the main reason Reyes’s parents uprooted her family from the Philippines for the United States in 2004. Reyes was just 9 years old. After the family’s tourist visas ran out, Reyes remembers her parents offering her a choice.

“My mom and dad sat us down. They had my brothers and I choose whether we would want to go back to the Philippines,” says Reyes. “My brothers and I decided to stay.”

The family became undocumented.

Now, Reyes is 23 years old and taking a full course load at a community college while working full time at the Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach office in San Francisco. It is here is where her intensifying limbo in her personal life collides with her workday. The nonprofit serves marginalized, Asian American immigrants in the Bay Area — and Reyes is the DACA outreach coordinator there. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals government program was created in 2012 to provide temporary work permits and relief from deportation to immigrants brought to the US as children.

Reyes is trying to help DACA recipients — and herself — navigate a confusing period, one that may be prolonged so long as Congress, the Trump administration and the highest courts in the country debate DACA’s future.

The Trump administration announced that it would phase out DACA on Sept. 5, 2017, arguing that the program bypassed Congress. In early January, a federal judge in California partially blocked the administration’s decision to end DACA. For some, the ruling offers a bit more relief. The government is now accepting renewal applications while legal challenges continue. Reyes, however, says she feels little comfort.

“It's just temporary,” she said. “I feel for me, it's a very confusing time. We never know what is going to happen. We aren’t in that room talking to [politicians], telling them what is good for us.”

In fact, the Trump administration has already appealed the ruling and plans to petition the US Supreme Court to hear the case.

The situation also has Reyes anxious about sticking to her studies. Her DACA status expires on Sept. 25, 2019, and so will her work permit. Without a court ruling or legislation, she does not know if she will be able to renew it. So, she asks, is it worth investing more cash and time in a higher degree?

“Right now, I’m transferring to a CSU [California State University]. What will I do after because I won’t have DACA? What will I do with this communication degree, what will I be able to do? No one is going to want to hire me without papers or without DACA or a work authorization.”

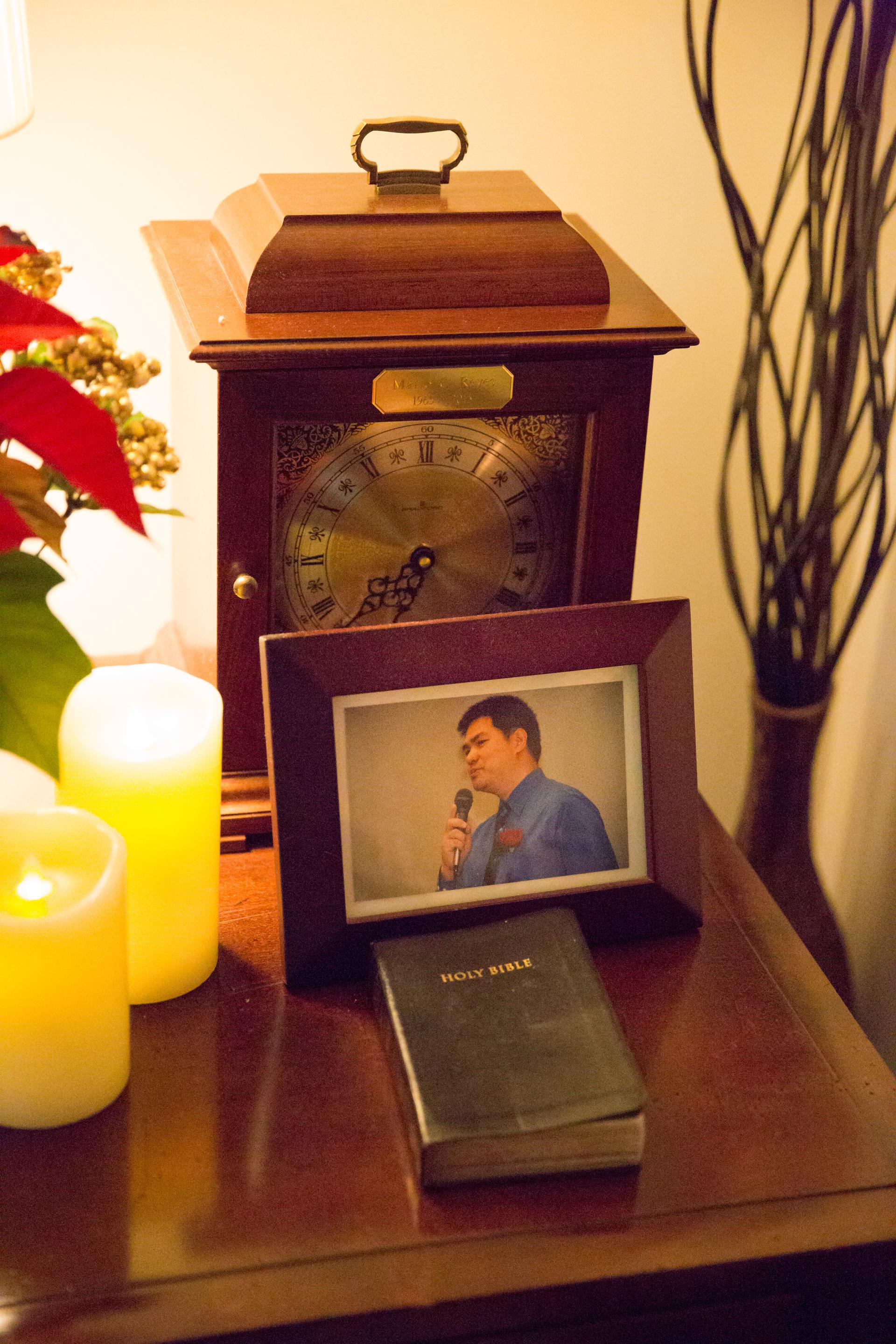

It is a far different time than 2012 when her dad first learned about DACA while watching the news.

“My mom and dad were able to borrow money from friends and family to pay for the application fees,” said Reyes.

Reyes and her three brothers were all eligible for DACA and enrolled. Most DACA recipients come from Latin America, not Asia. In September 2017, US Citizenship and Immigration Services reported less than 1 percent of DACA recipients came from the Philippines. According to the Migration Policy Institute, only 21 percent among the DACA-eligible population who are from the Philippines participate in the program.

Now, with DACA in free fall, Reyes feels herself slipping into a darker mood. When her family became undocumented, the term meant little to her, then a 9-year-old. But as she got older, she learned that living as an undocumented person means being unable to vote, travel out of the country or apply for most student loans.

The deepening uncertainty mirrors what happened to undocumented students before DACA’s implementation in 2012, according to some education scholars. Students without status had to carefully evaluate if going to school was financially and emotionally worthwhile, especially if there were no tangible benefits after graduating.

“DACA really changed that [mindset] significantly,” says Roberto G. Gonzales, a professor of education at Harvard Graduate School of Education. “You can go to a community college and transfer and get an internship and get a good job when you were done. The future of uncertainty was waived.”

Today, that intense anxiety is back, says Gonzales. Students like Reyes again feel forced to question whether a higher education is worthwhile if working legally becomes tougher while the prospect of deportation looms.

Also: Immigration limbo is a ‘tug of emotions.’ It’s also a mental health issue.

Reyes tries to remain hopeful and says she is intent on fulfilling her father’s dream that she get a degree. She hopes that Congress can work on a more permanent solution for undocumented immigrants like her.

“I’m really hoping that they see that [DACA recipients] can help our economy and can help people without rescinding it,” she says. “Because they’re basically taking it away from people who are like citizens.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!