Lagos’ megacity dreams are a nightmare for many working people

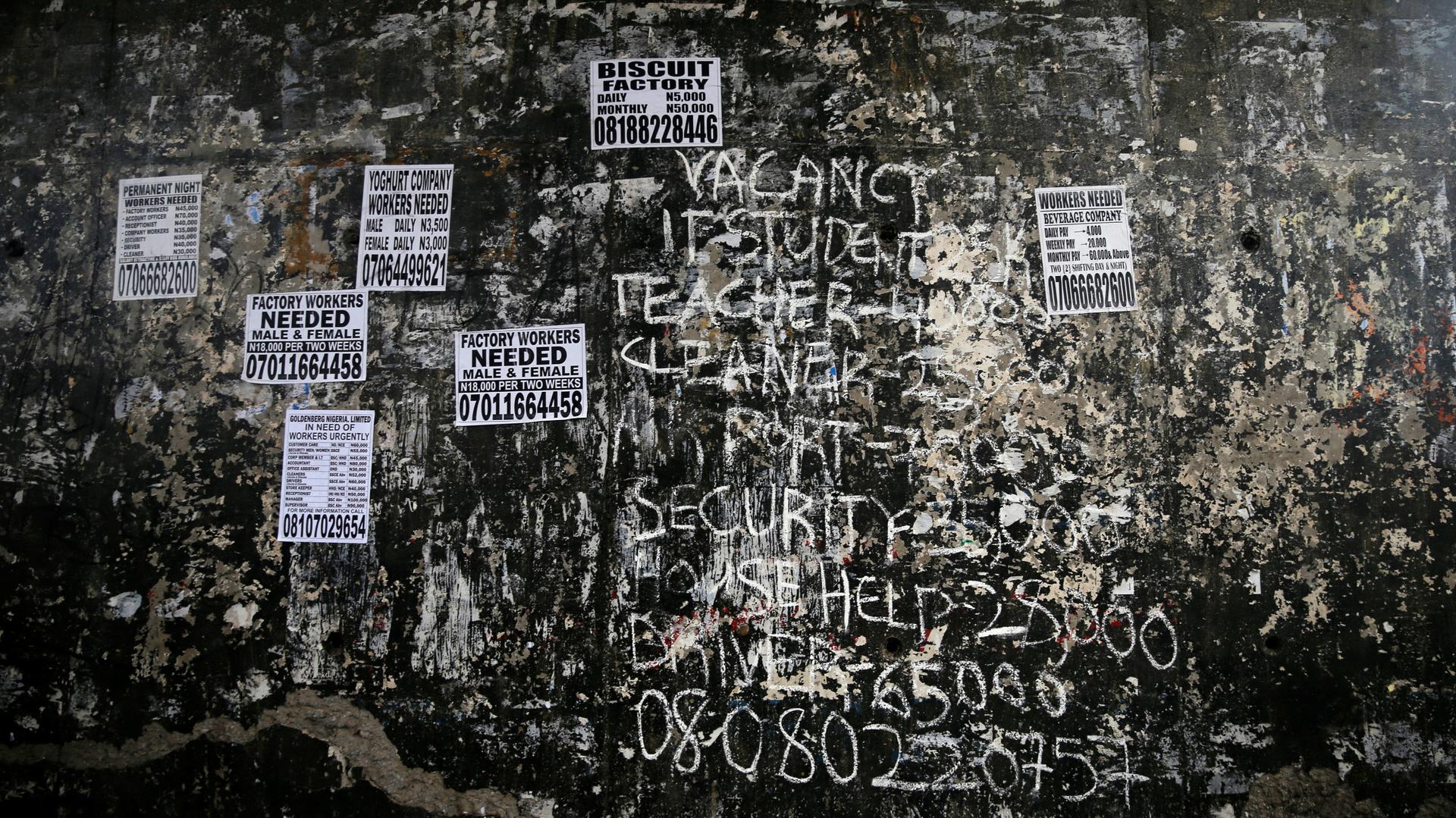

Signs advertise jobs on the wall of a bridge in Ikeja district in Lagos, Nigeria, Aug. 10, 2016.

Every Friday, at the close of work, Idris Oladipo makes his daunting commute home from the city of Lagos.

Oladipo is an account manager with Pulse Nigeria, one of West Africa’s biggest media companies. His commute takes him 100 miles from Pulse’s office in Lekki to his home in Ibadan, the capital city of Oyo State. The drive should take about two hours, but traffic often stretches it to four.

“Up until September of 2017, I used to have an apartment in Lekki, but the rent was increased after my [lease] expired.” Oladipo said. “Since September, I’ve sometimes slept in the office and now, I’m currently squatting with a friend that’s also my co-worker.”

Oladipo is one of an estimated 21 million people who live and work in Lagos, making it Africa’s largest city. It’s also one of the fastest growing cities in the world. In recent years, even as Nigeria experienced a recession, the commercial status of Lagos has led to a steady influx of people into the city from neighboring states. By some estimates, Lagos could double in size by 2050.

Lagos has actively pursued its megacity status. City officials and developers have undertaken a massive urban renewal project that has seen slum and waterfront communities demolished to make way for new high-rise building projects. These demolitions have led to an increase in the cost of housing and amenities in Lagos, especially on and near Lagos Island, the city’s commercial center. Critics say the megacity project is a form of gentrification, and not the type of urban planning needed to handle a budding population crisis. A recent update to the Lagos land use tax has threatened to make conditions even more challenging for people already struggling to live and work in the city.

Moses Fiarama, a real estate agent and Lagos resident, believes that everything in the city is overvalued. “The cost of housing in Lagos is too high compared to that of houses in Ogun and Oyo state,” she said. “But this is because everything exists in Lagos; [the] industries, jobs, means of production.”

For years, the steady increase in the cost of land and houses in the major metropolitan areas of Lagos has led to a population increase in fringe towns like Ikorodu and Iju, especially as the Nigerian minimum wage of 18,000 naira (about $50) often isn’t enough to go by. But in a country some say is becoming the poverty capital of the world, people will do what they need to work and eat.

When you can’t afford to live near your job, the commutes, like Oladipo’s, can be rough. Aisha Salaudeen, a journalist in Lagos, says the city hasn’t built the infrastructure to meet the demand for housing and transit.

“The government of Lagos hasn’t been able to hack housing and transport networks,” she said. “There is no functioning rail network, the roads are always congested and this means a lot of people will clamor for housing on the island, because that’s where most of the companies and jobs are. That was what drove the cost of houses and rent of the island up.”

But on Lagos Island, new types of housing have risen up. Some old buildings in Idumota have been repurposed as short-stay apartments, where often more than 20 people share bedless rooms each night. Some of these rooms are as small as 100 square feet.

For Kayode Alaba, a cleaner for a financial consulting company on Lagos’ Victoria Island, these apartments are a way to exist in the city while applying and waiting for better jobs — or for government policy to improve the standard of living in Lagos.

“When I finished with my education in the Ilaro Polytechnic, I moved to Lagos in 2013 because there were no jobs in Ogun State,” he said. “Lagos only provided me with jobs as a janitor and cleaner. Because accommodation is so expensive in Lagos, I sleep in a room in Lagos Island where I pay 150 naira [42 cents] a night. Sometimes, we are more than 25 in the room.”

While many residents of Lagos have been looking to alleviate economic suffering, a recent increase in the Lagos land use tax signed into law in February — the first update to the tax in 17 years — has caused more strain. (The land use tax combines all property and land-based rates and taxes payable under the laws of Lagos State.) The Lagos State government proposed and approved a 200 to 400 percent increase to the existing charge, as well as an increase in tolls and a few other charges.

The tax increases drew widespread public opposition. They increases are part of an effort to raise $50 billion that the state government says it needs to transform Lagos’ infrastructural landscape and cater to its ever increasing population. But the burden of the new tax would most likely be borne by tenants and business owners renting property in Lagos. Lagos State Governor Akinwunmi Ambode defended the changes, stating that it was well within the provisions of the law to update the land use tax every five years.

After protests by citizens, the Nigerian Bar Association and some landlord associations, the Lagos State government announced in March that it would lower the new rate: a 50 percent reduction of the original increase. But many people living in Lagos are still upset.

The main fear is that the price of apartments and space for offices and factories will keep going up, but the rising costs will be transferred to workers and residents who can least afford it.

“The incidence of this land use tax will fall onto the final consumers,” explains Iyinoluwa Owolaja, a freelance economist in Lagos. “Most people living in Lagos are tenants and not the landowners. The burden will be shifted in two ways. An increase in general rent levels, or a separate charge, much like a service charge on the homes. Entrepreneurs and traders that have to pay rents for their shops and business locations will definitely shift the extra costs down to the final consumers and this will increase the supply of money in Lagos.”

Tunde Braimoh, a lawyer and lawmaker in the Lagos State House of Assembly, believes the charge is necessary. “We already know that Lagos is one of the most populated states in the country,” he said. “This is why we need funds to put forward proper plans and structures in place. The government of Lagos State has a long-term plan especially as Lagos evolves into a smart city. One problem is the transport link and we are currently working on BRTs connecting satellite towns.”

BRTs are bus rapid transit lines, popular around the world as a lower-cost way of providing many of the same transit benefits as more expensive rail lines.

But many people already struggling to live and work in Lagos are skeptical of those promises, and feel Lagos is becoming a home for only those with financial power. As the megacity project unfolds, critics warn that commuters like Oladipo will be pushed farther and farther away from the city center, spending more of their time on congested highways, while workers like Alaba will continue sharing tiny bedless rooms with even more roommates to be near their jobs.

For Hakeem Saratu, a businessman living in Akute, Ogun State, but working in Lagos, there’s only so long people will accept those conditions.

“Every day, the prices of things go up. One day, the people will be unable to take the hardship and they will fight,” he said. “They will fight so viciously because they will have nothing else to lose.”

Oluwatosin Adeshokan reported from Lagos.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on The World. Please take our 5-min. survey.