Egypt targeted ‘fake news’ ahead of presidential elections

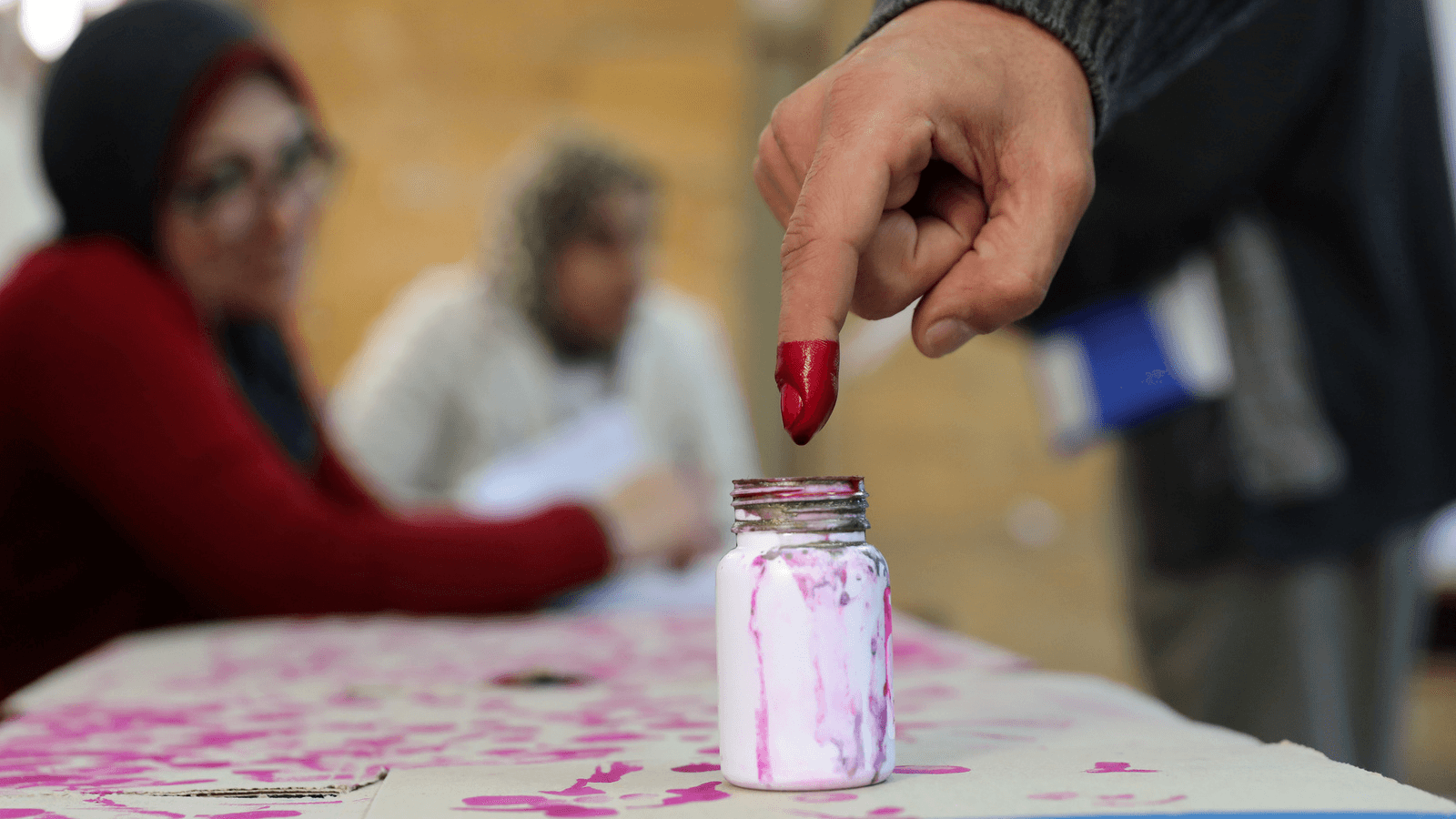

A voter's finger is marked with ink at a polling station during the second day of the presidential election in Alexandria, Egypt, March 27, 2018.

Egyptian TV host Khairi Ramadan probably never expected to fall afoul of the state; he is, after all, a well-known pro-government presenter.

So his arrest earlier this month for spreading “fake news and statements against the police force, therefore defaming it” over a segment where a police officer’s wife complained about low police salaries has shocked many in the media industry.

Related: Egypt is blocking access to news sites on an ‘unprecedented level’

The complaint was lodged by the country’s Interior Ministry over the episode, which aired on a state TV channel on Ramadan’s nightly talk show, Egypt Today, on March 3. Just two days earlier, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi warned that insulting the army or police amounted to treason. Ramadan was detained for two nights and is currently on bail.

For many, Ramadan’s arrest signals quite how extreme the campaign against the media has become in the lead up to the presidential elections currently underway, where the authorities are using charges of “fake news” to tighten censorship, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has warned.

This is even though Sisi is certain to be voted back in again in the elections in which he is running virtually unopposed, especially after any credible rivals were arrested or intimidated out of the race. The only challenger left has said he is a supporter of Sisi.

Related: In Egypt’s ‘joke’ election, Sisi’s only challenger is perhaps his biggest fan

At least four Egyptian journalists have been detained since Sisi confirmed his intention to run for a second term in January, according to the CPJ, for criticizing Sisi and for alleged ties with opposition or activist groups.

They include reporter Mai el-Sabagh and cameraman Ahmed Mustafa who were arrested on Feb. 28 while preparing a report on trams in Alexandria. The journalists were investigated for charges of possessing photographic equipment for the purpose of spreading false news. Both were released on bail last week.

Another reporter for Huffington Post Arabi, Moataz Wadnan, was detained last month after he interviewed a leading member of Sami Anan’s campaign team — the former military chief of staff who was arrested soon after he announced his intention to challenge Sisi in the elections. Wadnan is accused, among other things, of fictitious reporting that incites against the state.

Related: Egypt's revolutionaries grieve ahead of Sisi re-election

“It’s a nightmare to be a journalist in Egypt nowadays, unfortunately,” said journalist Khaled Dawoud, who is also the leader of the liberal Dostour Party. “Now you are going to be held liable for not just what you write but for doing the interview itself,” he said. “Even foreign media working in Egypt is not safe,” Dawoud added.

The attention of the authorities on foreign press has also increased of late after a critical BBC report last month on enforced disappearances in Egypt. The State Information Service, the government press center, said it was “flagrantly fraught with lies” and urged officials to refuse interviews with the BBC. A case for the closure of the BBC’s Cairo office over the report is due to be heard in court on April 10.

Shortly after the report aired, in a statement Egypt’s top prosecutor Nabil Sadeq ordered state prosecutors to monitor media reports for fake news and to take action against those outlets. He said that “forces of evil” have recently been trying to “undermine the security and safety of the nation through the broadcast and publication of lies and false news.”

The authorities also published a list of telephone numbers two weeks ago, asking ordinary Egyptians to help monitor and notify them of such reports by WhatsApp or text message.

Then a week ago the British publication The Times revealed its correspondent, who had lived in Cairo for seven years, had been deported in February without explanation — despite intervention by British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson.

Sisi said people "are free to express their opinion" in Egypt, in a TV interview that aired ahead of the elections.

“We have a regime that’s against freedom of expression,” said Gamal Eid, a prominent activist and executive director of the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information. “They are trying to control everything,” he added.

Censorship has increased drastically under Sisi, who was elected president in 2014, a year after he led the military ouster of Egypt’s first democratically elected leader, Mohamed Morsi, following popular protests.

In Reporters Without Borders’ 2017 ranking of media freedom, Egypt placed 161 out of 180 countries. Since May last year, the Egyptian authorities have also blocked nearly 500 websites, including news outlets, blogs, human rights organizations and VPNs.

“The escalation [against the press] is following a clear trajectory and it’s been trending in this direction for quite a long time,” said Timothy Kaldas, a non-resident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. Kaldas says this is the case because the Sisi government is facing little pressure from states in the West.

“They don’t see any consequences and increasingly there are none. Increasingly the rest of the world is preoccupied with other concerns and so the push-back is less and less than it used to be, the criticism is much less than it used to be,” Kaldas said.

With the elections nearly over now, some will be hoping that authorities might ease on the press after Sisi is re-elected.

Kaldas doesn’t think so. “There’s a real possibility that they are going to go further in the coming year and I’m worried about that,” he said.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to include additional information on a deported British journalist and quotes from President Sisi.