"Giant" by Moath al-Alwi.

I first saw the ship a year ago, in an abandoned prison cell.

“Giant” is an intricately detailed model galleon, something that, at a casual glance, you might expect to see in a museum. It's also a dramatic contrast to its surroundings — a decrepit, high-security isolation cell in Guantánamo’s Camp 5. The prisoners were being slowly moved to Camp 6, where the dwindling number of low-security detainees were being consolidated.

But on closer inspection, the magnificent ship revealed its origins in the prison, a product of the limited supplies and tools prisoners had to work with. There is no wood in this wooden ship. It’s cardboard and glue, stained with coffee grounds. The sails are made from old shirts, their billows frozen open with glue, which also stiffens the intricate rigging made from unraveled prayer caps.

It’s a remarkable piece, but it had only been seen by a handful of people: guards, lawyers, detainees and the few journalists allowed inside the high-security facility. But today it sits in an art gallery in Manhattan, part of the exhibit Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantanámo Bay at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Erin Thompson is an art professor at John Jay and the curator of the exhibit. Her work has focused on the intersection of art and criminality — people stealing, say, or destroying art, the way the Taliban had obliterated Buddhist statues in Afghanistan. She was surprised to find war-on-terror detainees making art.

“One of the lawyers for detainees approached me and said, ‘I want my clients' art to be exhibited.’ I said, 'What do you mean? There's art made at Guantánamo?’" she says with a laugh. The lawyer took Thompson to her office "and just opened file cabinets full of paintings in her law office in Midtown Manhattan and showed me all these images of the sea created by her client."

“I thought, ‘All right. This must be an exception. Maybe one client gives her a lot of art, but this can't be true.’ I started reaching out to more lawyers for more detainees and found that, actually, all across New York, all across DC, there are lawyers with file cabinets full of art who thought it was a good idea to display them.”

Aliya Hussain is a lawyer for the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), which represents a number of Guantánamo detainees. She says the lawyers develop “very close relationships with our clients. We're really their only connection to the outside world in real time.”

Two of CCR’s clients, Ghaleb al-Bihani and Djamel Ameziane, are represented in the show. Both men were cleared for release by review boards under President Barak Obama. Ameziane, who was released to Algeria in 2013, “describes his artwork as a way to express his feelings largely about the uncertainty of his life, things he was deprived of, things he dreamed of,” according to Hussain.

The eight detainees whose work is represented are a mix that well represents the current population at Guantánamo. Four of them are no longer in detention; having been deemed no longer a threat to the United States, they were released to various countries under President Obama. Then there are more ambiguous cases, like the shipbuilder, Moath al-Alwi.

Alwi was initially assessed as an al-Qaida fighter and one of Osama bin Laden’s bodyguards. A 2016 review board said he was “probably not” one of bin Laden’s bodyguards and may not even have been engaged in combat, but he has remained detained without charge.

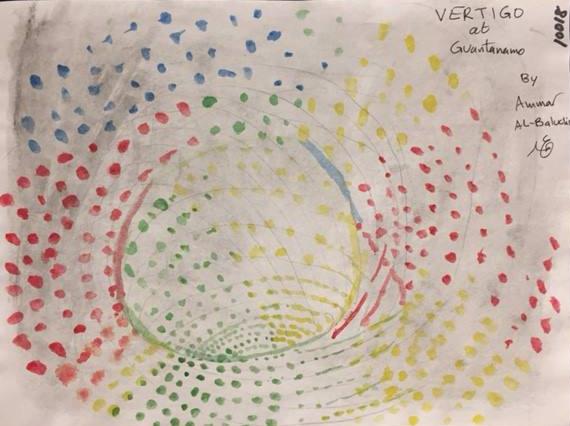

The most notorious among the artists is Ammar al-Baluchi, currently on trial in a military commission for his alleged role in supporting the 9/11 plot and hijackers. For three years he was held in a CIA "black site," where he was tortured. His one piece of art in the exhibit, “Vertigo,” reflects that torture.

“It's just a swirl of lines and dots,” says Thompson. “He drew it to show his lawyers what happens when he experiences vertigo, when he can no longer see,” episodes his lawyers say are triggered by a brain injury he suffered during his beatings in CIA custody.

I had the unique opportunity to speak with one of the artists who is still detained in Guantánamo, in December 2016. Khalid Qasim, a Yemeni who has been detained at Guantánamo since 2002, shouted out to our PBS-Frontline crew as we were filming at the prison. Although the authorities required us to delete our recordings, he told us his name and his prisoner number, 242, which he signs on his paintings.

His artwork ranges from the abstract to the surreal.

He’s fond of mixed media, working gravel from the prison ground into some of his paintings, and creating elaborate sculptures out of discarded materials like MRE boxes.

All of the art had to pass through a security review before it could leave the island, which is why there aren’t depictions of scenes from the prison, force-feeding or CIA torture techniques. But there are subtle signs if you know where to look.

Ahmed Rabbani says he’s in Guantánamo because he’s a victim of mistaken identity, and his supporters claim his confessions of ties to al-Qaida were a product of his torture by the CIA. His imprisonment has been defined by years of hunger strikes.

He’s painted a still life of empty bottles and glasses. And binoculars without viewers behind them, gazing emptily at the moon.

The title of the exhibit, “Ode to the Sea” is a nod to the pervasive images of the ocean in the artwork — sometimes peaceful, other times ominous with shark fins or ships violently wrecked.

There’s more than one depiction of the Titanic. Muhammad Ansi, in one of the last groups of detainees released just days before President Donald Trump took office, took the image from an interrogation. Thompson says this is because “in his first interrogation with a female interrogator, they showed him the movie 'Titanic' to try and create rapport with this interrogator.”

Another former detainee, Abdulmalik al-Rahabi, painted scenes of a city by the water, a suspension bridge at sunset. Over a Skype call from his new home in Montenegro, he told me how he used to imagine “my life in Guantánamo, like I am in the sea, in the middle of the sea. When I think about that, about the sea, the big sea, I imagine one day the boat will come … [that] one day, I will go out.”

As we spoke, I took him on a virtual tour of the gallery displaying his work, and he showed me many more paintings he produced at Guantánamo that he now hopes to sell.

Erin Thompson understands that some people might find that disturbing, along with the notion that this art might elicit sympathy for people some consider America’s enemies. But, she says, “the show is of interest no matter what side you fall on, no matter what you believe about these men. Is it that you want to see the humanity of them as victims or do you want to understand better the enemy? You can do either by looking at these works.”

The show still has its share of critics, including some 9/11 victim family members. Upon learning that some of the detainee artwork in the exhibit was for sale, the department of defense stopped the transfer of detainee artwork out of the facility, and some lawyers reported that their clients were told excess art would be destroyed, even burned. The Pentagon says the claims of destruction are false, though it has suspended the transfer of artwork out of the prison pending further review.

This piece originally appeared on WGBH.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?