What does protest sound like? For this Philadelphia activist, it’s the eight-string jarana.

Yared Portillo, an activist from Philadelphia, uses the jarana, a small guitar-like musical instrument, and son jarocho, a type of music from Veracruz, Mexico, in her community work. During protests, Portillo brings her jarana and plays music as demonstrators chant.

Yared Portillo, a Philadelphia community activist, has four of them: One she built from scratch; two others were secured from renowned artisans; the final one — received broken and in pieces from a friend — she carefully repaired and made whole again.

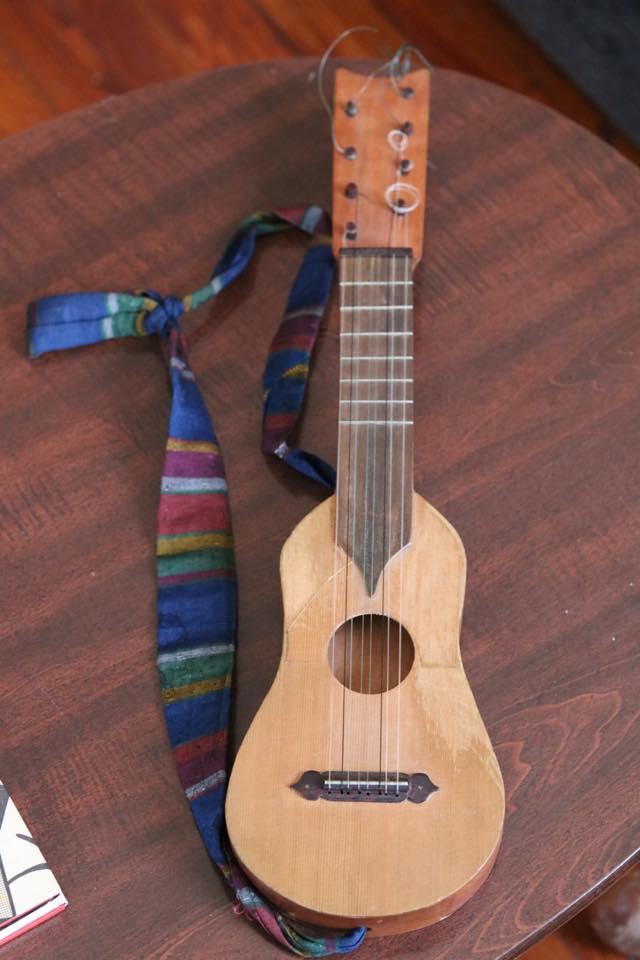

The repaired instrument isn’t a bad metaphor for the role the jarana has played in the US immigration protest movement for the past two decades. It's a small, eight-string instrument from Veracruz, Mexico, patterned after a 16th century baroque Spanish guitar that is often confused with a ukulele.

In the hands of Chicanos or recent Mexican immigrants, the jarana — as well as the son jarocho musical form with which it is inextricably associated — energizes rallies and undergirds the chants of those who want to repair not only a broken immigration system, but the increasingly broken relationship between two nations sharing both borders and histories.

In Philadelphia, Portillo punctuates chanting while strumming the tiny, “mosquito”-size jarana during a protest rally at a local Immigration and Customs Enforcement headquarters: Me gusta la lima, me gusta el limón, pero no me gusta la deportación. I like lime, I like lemon, but I do not like deportation.

In California, the alt-folk group Las Cafeteras uses jarana and the same chant as Portillo in their song "Señor Presidente," one of 10 cuts on their new album “Tastes like L.A.” In Chicago, members of JaroChicanos use the larger primera- and segunda-size jaranas to sing the praises of Mexican immigrant and congressional candidate, Jesús “Chuy” García, to the tune of the most famous son jarocho: "La Bamba."

And every year for a decade, jaraneros on both the Tijuana and San Diego sides of the border wall gather in an event called Fandango Fronterizo that lets the sound of the sharp, bright instrument cross freely where people cannot.

Portillo, 24, described the jarana as an instrument that is small but sings big — está chiquito, pero canta fuerte.

A Gates Millennium Scholar born in California to parents who immigrated from Sinaloa, Portillo has been playing the instrument and learning about the traditions of son jarocho for the past three years.

“One of the things that initially drew me to son jarocho was that it seemed to be a powerful music of resistance. Its historical (and current) use of indigenous and African elements in a space that was demandingly European has always seemed to me a radical act of resistance through art and existence," she said via email. "I remember when I first started learning about son jarocho coming across articles that framed son jarocho as the music of resistance and imagining that to be at the heart of the music and the tradition."

Portillo said an instructor told her that the word jarana comes from the Arabic word haram, meaning something that is forbidden.

“The word then transitioned from ‘jarameros’ to ‘jaraneros,'” she said. “And consequently, the instrument the jaraneros used was the ‘jarana.’”

Also: You may not know it — but if you speak Spanish, you speak some Arabic too

The jarana’s long history in its native Veracruz is fraught with prohibition and warnings about its subversive nature. The instrument is referred to as “la costilla del diablo” — the devil’s rib bone — in one traditional song called “El Buscapiés.” Legend has it that the devil finds that particular song played on the jarana irresistible and shows up to dance at any fandango, or festive gathering of community and jaraneros, at which it is played.

In a documentary about the indigenous Nahua-Popoluca Fandangos in the mountainous area of Veracruz, the jarana is characterized as intrinsically rebellious. According to son jarocho expert Cirilo Morales Reyes, Catholic priests long urged the indigenous population not to permit their children to play the “evil” instrument.

Claims aside, the instrument’s small size, distinct voice and deep roots in Afro-indigenous tradition have made it a good tool for community building, particularly in marginalized communities, according to Zenén Zeferino Huervo.

Zeferino, a traditional master jaranero from Veracruz with whom Portillo has studied at US workshops, has dedicated the past 40 years to the preservation of traditional music in his homeland.

“That is what I have fought for,” he said by phone. “To engage people and strengthen community through music.”

Portillo has aimed to do the same since she came to Philadelphia about six years ago. She worked as a staff member of the immigrant advocacy group Juntos for several years and started playing her jarana at one of the group’s civil disobedience protests in December 2013.

“From then on, whenever I could, I would bring musical instruments with me to actions, or we would invite other musicians in our community,” she said. “I believe that music and art add power to movement community building, and so whenever I can I make the effort to incorporate music, even if just for a brief moment.”

She founded Son Revoltura, a group of Philly jaraneros, in 2015. The group, which has about two dozen members, are a diverse bunch, ranging in age from 7 years old to senior citizen, and in occupation from students to construction workers.

“The lyrical practice of son is shaped around singing about your experiences,” she added. Instead of singing about life in rural Veracruz, Son Revoltura “might sing about what's going on at 9th Street, or about la polimigra [immigration police], or about different parts of our experiences as immigrants and Latinxs in Philadelphia.”

How another artist mixes politics and music: Musician Lila Downs fights back

At the local level, jaraneros know and are part of the communities they sing to and protest with. That kind of connection is harder on a national level, but there is a strong desire to forge bonds not only between communities but between the jaraneros themselves.

The Fandango Fronterizo, a national event that draws hundreds of jaraneros to San Diego, is one of the ways that connection happens. On the day of the annual fandango, a set of gates is opened on the US side, permitting participants to get close to the border fence to play within arm’s distance from their counterparts in Tijuana — within a four-hour window — while US Border Patrol agents keep watch. Adrián Florido, one of the Fandango Fronterizo’s organizers and an NPR reporter, told the LA Weekly in June that “for some people, it is explicitly political. For others, they think of it as a beautiful, symbolic thing.”

The US jaraneros who can’t make it to San Diego find a way to participate remotely. The members of Son Revoltura have never been to the Fandango Fronterizo, but they have held solidarity fandangos on the same day. In 2016, they recorded themselves performing "El Son Del Presidente" (the president’s sound) at the same time it was being performed at the national event.

As with the jarana itself, the resistance at the heart of (and in the history of) the son jarocho makes it an inherently political musical form. It is impossible to hear "El Son Del Presidente" without being reminded that President Donald Trump has proposed to turn the border fence where the Fandango Fronterizo takes place into a wall.

“As a musical form that was created as a consequence of slavery, colonization and the amalgamation of African, indigenous, Spanish and Arabic influences, [son jarocho] is part of Mexico's musical resistance to keep the African and indigenous stories alive,” said Héctor Flores, who plays jarana and sings vocals for Los Angeles-based group Las Cafeteras, in an email. “I would believe that anyone who learns about the history of the instruments, songs, dance and poetry, would also be connected to modern-day struggles for solidarity and resistance.”

Las Cafeteras’ first encounter with the jarana and son jarocho came in 2005, at a community concert to save an urban farm in South Los Angeles. Zach de la Rocha from Rage Against the Machine rocked the mic with Los Cojolites, a son jarocho band from Veracruz, and Quetzal, an LA rock band.

There, Flores recounted, “a movement in Northeast LA was born.”

Inspired, a group of students and community activists began to learn about son jarocho at the Eastside Café, a community center that two members of Las Cafeteras — Denise Carlos (vocals, jarana) and José Cano (cajón, Native American flute, harmonica) — had helped found in the early 2000s.

None of the group that would eventually become Las Cafeteras had a musical background, and none had ever played a jarana before, but they knew they wanted to bring it into the mix of music that reflected their neighborhoods and barrios.

”We are not trying to be a son jarocho band. We use traditional son jarocho instruments and non-traditional instrumentation to create sounds that combine our mixed identities as Chicanx and Native folks who grew up in Los Angeles,” Flores said. “Son jarocho taught us to tell our stories because that is how our people stay alive. We are not jarochos and don't claim to be. We are Chicanx kids and we also have stories.”

Since most of the members of Las Cafeteras have worked as organizers and advocates for immigrant families their music is quite explicitly pro-immigrant.

“La Bamba Rebelde,” one of Las Cafeteras’ popular songs from their 2010 album "It’s Time,” has the line, "Yo no creo en fronteras," or "I don’t believe in borders," as part of its refrain. The band performs in front of a banner that proudly proclaims the same during their live shows.

“Many of our songs deal with the hidden stories of migrant families in Los Angeles and beyond,” Flores said. “On our new album, ‘Tiempos de Amor’ is a song written in response to Trump-era attacks on migrant families. Our rendition of ‘This Land is Your Land’ is a Zapatista-inspired Mexican Norteño jam that swings from English to Spanish.”

Jaranas are especially visible in December. The posadas at Christmas time bring jaraneros out into the streets of Mexican neighborhoods in cities big and small across the US.

Las Cafeteras are on tour nationally with gigs through April.

And whenever a decision about Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, DACA, comes down — whichever way it goes — the jarana will be there, with the young immigrants whose experiences the instrument has amplified so uniquely. But not all jaraneros are glad that the voice of this traditional folk instrument is now so closely tied to the immigration movement.

“I've come across teachers in the tradition who lean both ways,” Portillo said. “While some concede that the music has the potential to be a revolutionary practice, others argue that the music is being unnecessarily politicized.”

For Portillo, it is all about context.

“I believe that here in Philadelphia, in a country where English is the dominant language and our Latinx community's access to traditional and cultural education is limited, [son jarocho] that at its rural roots offers a space for convivencia [coexistence] and experiencing life through verse and music, is absolutely a radical act of creation, life, community and resistance.”

More on music and movements: An Indian American Muslim singer resurrects an old civil rights anthem

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?