Martin Luther King’s 1967 speech opposing the Vietnam War ended a historic partnership with Lyndon Johnson

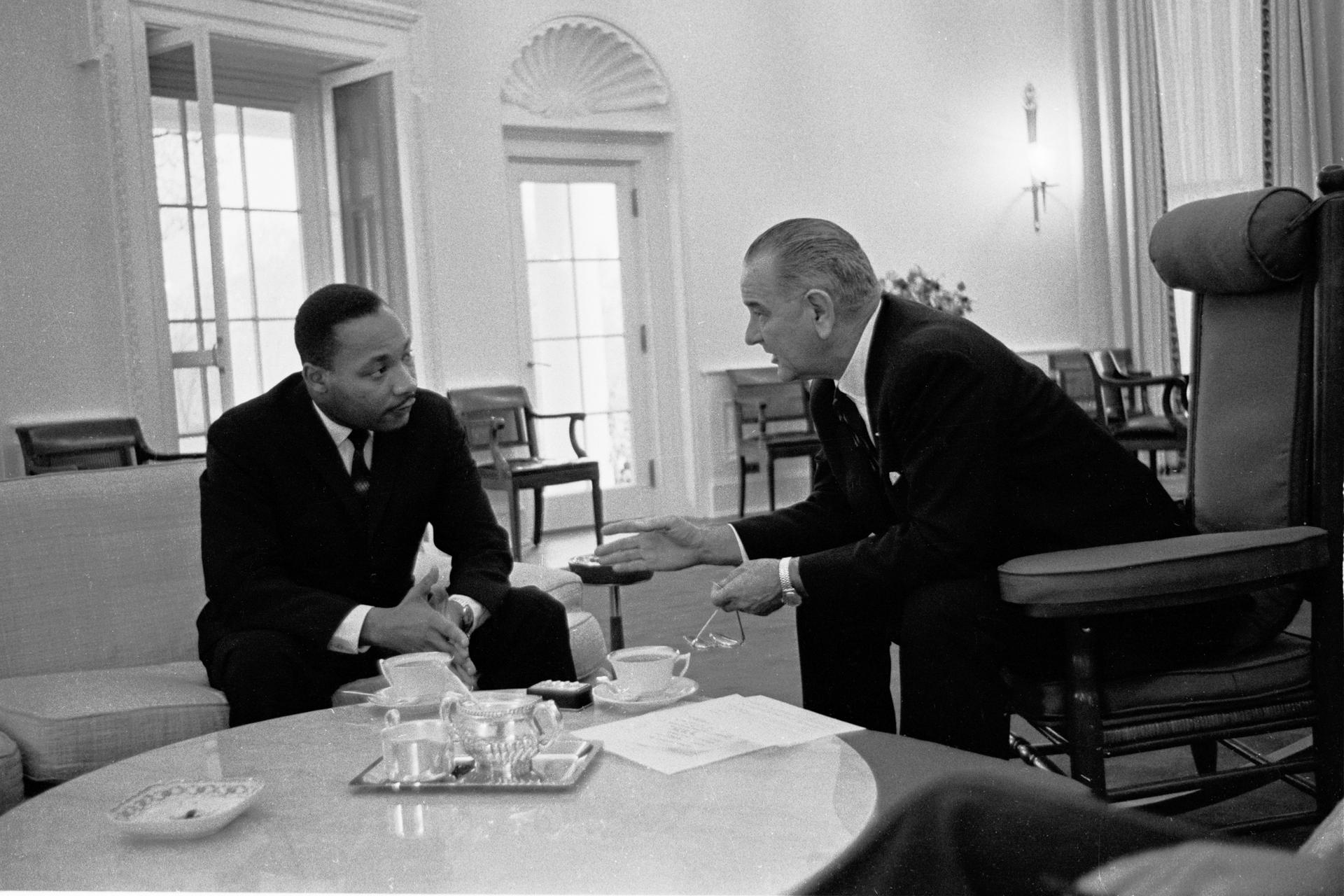

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Martin Luther King Jr., Dec. 3, 1963.

In early April 1967, an influential voice was raised for the first time in opposition to the Vietnam War: Rev. Martin Luther King Jr..

“I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice. A time comes when silence is betrayal. That time has come for us in relation to Vietnam,” King said. “The world now demands that we admit that we have been wrong from the beginning of our adventure in Vietnam. In order to atone for our sins, we should take the initiative in bringing a halt to this tragic war.”

Listen to King's entire speech here

For the 3,000 anti-war faithful who jammed into New York’s majestic Riverside Church to hear King speak, his decision to break his long public silence on Vietnam was cause for celebration. For King, the decision was fraught with political danger.

Whatever his private misgivings about the war, taking them public risked antagonizing President Lyndon Johnson, the architect of that war and the man who had done more for the cause of racial and economic justice than any president since Abraham Lincoln.

Andrew Young, a confidant and close aide to King, said in a 1970 interview: “Dr. King was always very optimistic about President Johnson. … I think we thought that here was a guy who could get things done, who knew the legislative machinery of the government. Dr. King used to always say that if a Southerner ever really gets converted, then there’s no better ally.”

Recognizing what the new president could mean to the nation's poorest citizens, King was among the first to offer public support after the Dallas assassination put LBJ in the Oval Office.

Listen to their conversation here:

“Certainly, after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, King took him at his word that Johnson was going to go much farther than any other president, before or since, to try to implement programs that he thought were essential as part of his ministry,” says historian Clayborne Carson.

For Johnson, striking the right political balance with Dr. King was a tricky proposition. By the summer of 1964, Johnson was already preparing to face Republican Barry Goldwater in the November election. While he needed King’s behind-the-scenes help on the legislative agenda, too cozy an association in public could hurt him with the crucial white, Southern vote.

A recorded conversation between Johnson and his press secretary, George Reedy, revealed many years later Johnson’s intense agitation with this situation:

Hear how LBJ sought to downplay his contact with King here:

As it happened, LBJ carried the black vote by huge margins and won the white vote as well, beating Goldwater by 23 points. King was among Johnson’s first post-election thank you calls.

Listen to LBJ's post-election call to King here:

But in the spring of 1965, the first cracks began to appear in the Johnson-King alliance.

“The whole idea of paying for guns and butter at the same time: That becomes Johnson's dilemma,” says Carson. “How is he going to afford the war abroad and the war against poverty at home at the same time?”

As LBJ ratcheted up the war, committing more troops and escalating the bombing of North Vietnam, the elephant in the room became too large to ignore. “We began to see very early that Vietnam was what it’s now come to be,” Jordan says. “We began to see that the crisis in the cities was demanding the funds that were now being diverted to Vietnam and that the domestic crisis was more dangerous and therefore more important to the country.”

From 1965 through 1966, a long struggle ensued for the hearts and minds of the black community. Young says the Democratic Party even started organizing meetings against King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council.

“They had a conference of preachers in Detroit. They pulled together all the Negro newspaper editors to support the administration’s stand,” Young explains. “We then had to do something to counteract that. So, the Johnson administration was pulling the preachers together one week and we pulled them together a month later and explained our side.”

Young says by this time, King and his allies had lost faith in Johnson. They didn’t doubt the sincerity of his commitment to civil rights, but they felt he had “gotten himself trapped and was basically blind to what was going on around him.”

Young's summation of what happened to LBJ in Vietnam still seems valid today. Johnson had indeed gotten himself trapped: between those who wanted to end the war and those who sought to prosecute it more aggressively; between fear of igniting a larger conflict and fear of being the first president to lose a war; and between guns and butter.

“I was determined to be a leader of war and a leader of peace,” LBJ told an interviewer not long before he died, “and I believed America had the resources to provide for both.”

In this belief, Johnson proved mistaken — a miscalculation that would cost him and the country dearly.

This article is based on LBJ's War, a podcast hosted by David Brown.