Salman Rushdie’s new novel centers on a billionaire real estate mogul who has ‘Trumpy echoes’

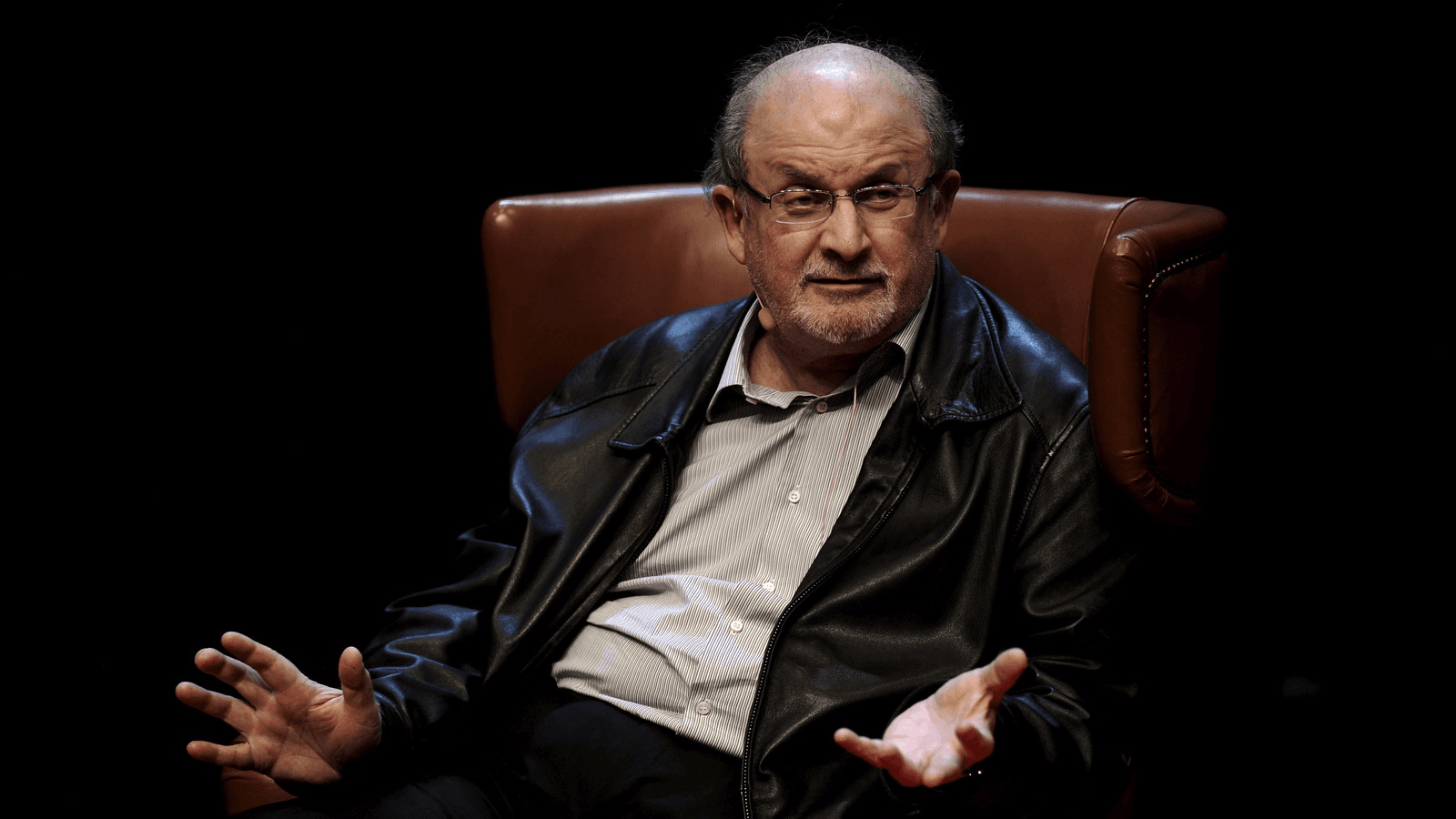

Author Salman Rushdie gestures during a news conference at the Niemeyer Center in Aviles, Spain, Oct. 7, 2015.

Salman Rushdie is the author of 12 novels, but he’s still best known for his 1988 book “The Satanic Verses.” It garnered charges of blasphemy from Islamist extremists and even led to the ayatollah of Iran placing a $6 million bounty on Rushdie’s head. Rushdie stretched the bounds of realism and fantasy in “The Satanic Verses,” but in his latest novel he’s doing the opposite.

“The Golden House” is out this week, and it tells the story of Nero Golden. He’s rich, he's a real estate businessman with three sons and a series of wives, he longs to see his name on buildings in big letters, and he loves to boast about his dominance. Sound familiar? Though there may be some parallels to President Donald Trump, Rushdie insists it’s Nero Golden’s Indian identity that’s vital here.

“He really had his point of origin in Indian billionaires,” Rushdie says. “In Bombay, which is Mumbai, which is my original hometown, it has more billionaires in it than more or less the rest of Asia put together. I’m quite familiar, over the years, I’ve become familiar with the Indian super rich. One of the things that really interested me was the intermingling — the world of the super rich on the one hand, the criminal mafias on the other hand, and then the intermingling of the Bombay criminal mafias with international jihadists coming from Pakistan.”

For the last decade, Rushdie says had been interested in crafting a character like Nero Golden, who sits at the nexus of this intermingling world.

“I suppose I did, at least for comedic reasons, give him some Trumpy echoes, but he is really quite unlike anyone else we know,” he says. “Really, the big question that the character asks, that the novel asks in a way, is whether it’s possible for somebody to be evil as well as good.”

Overall, now that the truth has seemingly come under attack in everyday America, this surrealist novelist is trying to get real.

“We do live in this very strange moment where reality itself seems to be under attack,” Rushdie says. “Certainly it has an effect on me as a writer of fiction — that’s to say as a writer of ‘untruth.’ One of the reasons why this book sort of abandons magic realism, surrealism, all this stuff that I’ve been associated with, is because I thought when there’s so many lies out there, when there’s so much fiction-making being done in the real world, maybe, paradoxically, it’s time for me as a fiction writer to start making the books as truthful as I can. So that did play a part in the form, language, and style of the book.”

While everyday news articles continue to become more and more surreal, Rushdie says his work fits into a “world turned upside down.”

“It's authoritarianism 101 — first you have to undermine the people who are trying to tell the truth, and then you are able to substitute your own truth for that,” he says. “Then you have to, to put it mildly, have a cult following which seeks no validation other than, ‘You say it and therefore it's so.’ In a way, it’s a different book from the one I wrote because that's the reality we are living in right now, and like many writers, I'm not exactly sure how to respond to it yet.”

For now, Rushdie says he’s waiting to see what’s to come for America.

“Like so many of us, I’m wondering if this is a passing phase or the beginning of a new reality,” he says. “I think it might be a time in which reportage is as important as imaginative fiction. … For now, I feel that there is a change in my personal weather, and I don’t really feel like writing fairy tales right now.”

A version of this story originally ran on The Takeaway.