In Texas, a model of what to do with unwanted Confederate statues

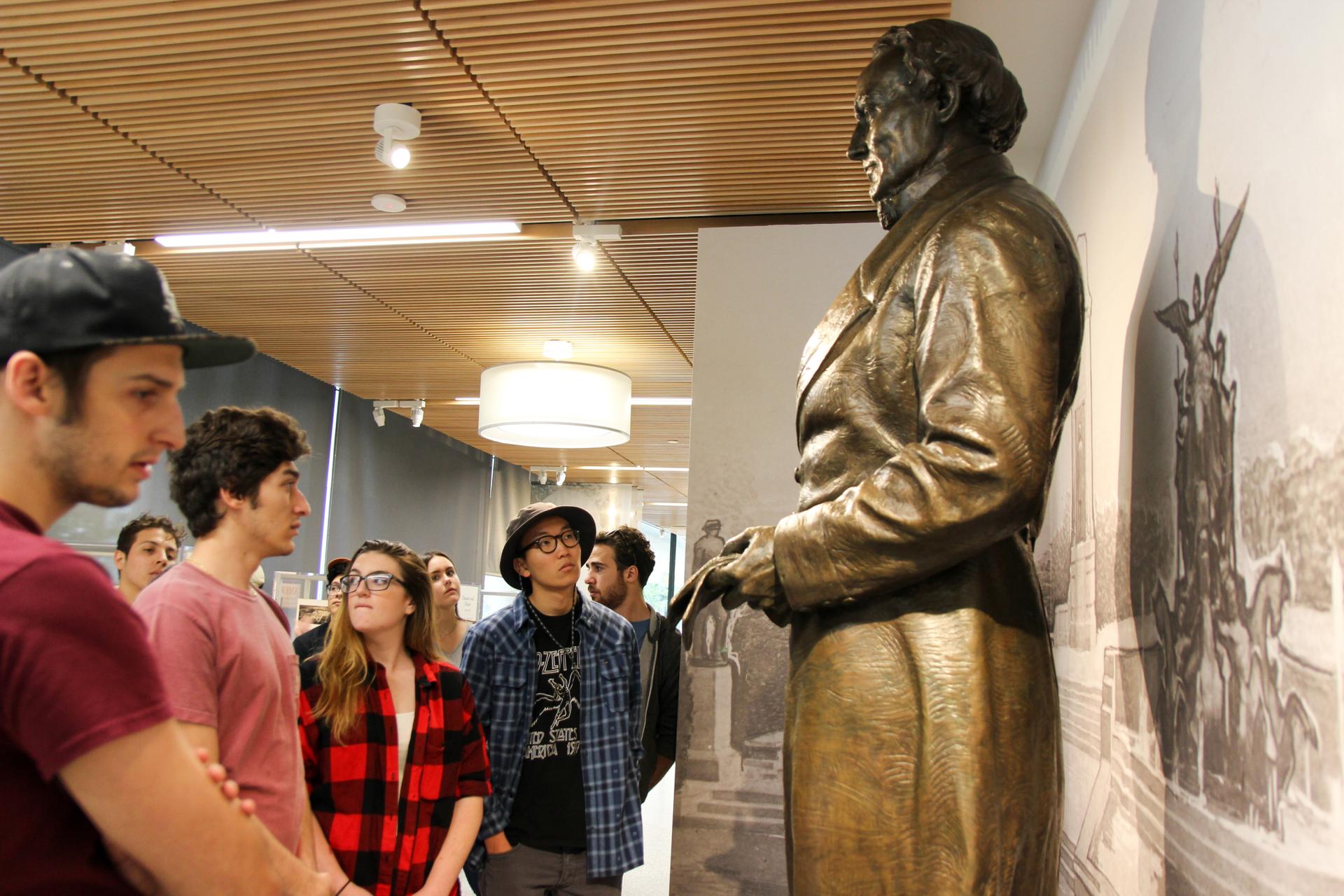

Students at the University of Texas at Austin visit the Jefferson Davis exhibit at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis looks in fine shape — all 8.5 feet of him — under the lights of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

Gone are the bird droppings, graffiti and festive tokens such as pumpkins and Santa hats that adorned him when he overlooked the South Mall at the University of Texas at Austin campus.

Now, following an expensive cleanup in Chicago, he looks brand new — and as divisive as ever.

“Some students criticized the fact we cleaned him up so well and have him lit nicely; others say he should be turned around to face the wall,” Ben Wright, curator of a new exhibit on the statue’s torrid history, says of the 1,200-pound rendition of this most controversial figure from the American Civil War.

The Davis statue’s 80-year tenure at the university was always accompanied by calls to bring it down, Wright says. But calls intensified in 2015 after the shooting by a 21-year-old white supremacist inside a Charleston, South Carolina, church that killed nine African Americans.

The exhibit appears to offer one solution as localities around the country come to grips with whether to remove hundreds of statues of Confederate leaders.

“I appreciate the idea of an exhibition leading to a full conversation about our history, and not just the raw facts, but a more philosophical one about the production of history and popular memory," says Kevin Foster, a UT African and African Diaspora Studies professor, adding the statue’s removal was the only option.

“Until you are up close, you don’t realize how big and impressive these statues are — they are just too powerful to contextualize with, say, an additional plaque explaining their context.”

But the center’s exhibit has its critics, too.

“Nothing is mentioned about why the statue was there in the first place, honoring Davis for his role as an American statesman and as secretary for war for the US,” says Marshall Davis, spokesperson for the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Texas Division, which took the university to court in an effort to keep Davis in its outdoor location. “It’s only current public opinion that’s making his connection with the Confederacy contentious.”

The question about how history is perceived over time has been a significant feature during debate about the statues.

“Erasing tokens of the racial past is no way to deal with that past; you’re just erasing memory,” says Glenn Peers, a UT history of art professor, standing in front of another empty plinth on the South Mall after the university decided to remove the remaining Confederate statues following the incidents in Charlottesville last month. “They might have served a purpose standing here.”

But Don Carleton, the Dolph Briscoe Center’s executive director, and a published historian himself, notes how history has a knack for remaining indomitable.

“We’re investing a tremendous amount of meaning in these statues in terms of changing or erasing history — if only it was so simple. There’s a lot of history I’d erase, but we can’t do it,” Carleton says. “As symbols of public values, they had to come down. As historical artifacts, they needed to be preserved. And that’s what we’ve done.”

Even those whose livelihoods depend on statues acknowledge the problematic nature of Confederate-related ones.

“To look at these symbols and be thinking they are benign park symbols is just ludicrous,” says Ivan Schwartz, whose career at his New York studio has involved making historical sculptures ranging from pop and sports icons to renowned individuals such as Thomas Jefferson, Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.

“These statues address a kind of longing for the Confederacy — they came about at the two main moments when whites of the South felt threatened, during Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and then the great civil rights movement.”

But Andrew Young, former mayor of Atlanta and lifelong African American civil rights activist, has spoken publically cautioning against all the attention on the statues as distracting from the underlying unaddressed racial issues that keep fanning the flames of civil discontent.

“With the visibility of racism now on Facebook and Twitter, it’s made me more wary when I’m out during the day,” says 22-year-old Anieph Gentles, a UT educational psychology graduate student. “I didn’t used to take any notice about being the only black person in a class, but now I wonder about it more.”

Despite African Americans making up about 12 percent of the Texas population according to the last census, only 3.9 percent of UT’s student body is African American.

“Removing the statues is not going to sort out the real problem that UT has, which is its disproportionately low number of African American students,” Foster says. “Addressing the state educational laws and university polices that lead to the composition of the student body is the real challenge.”