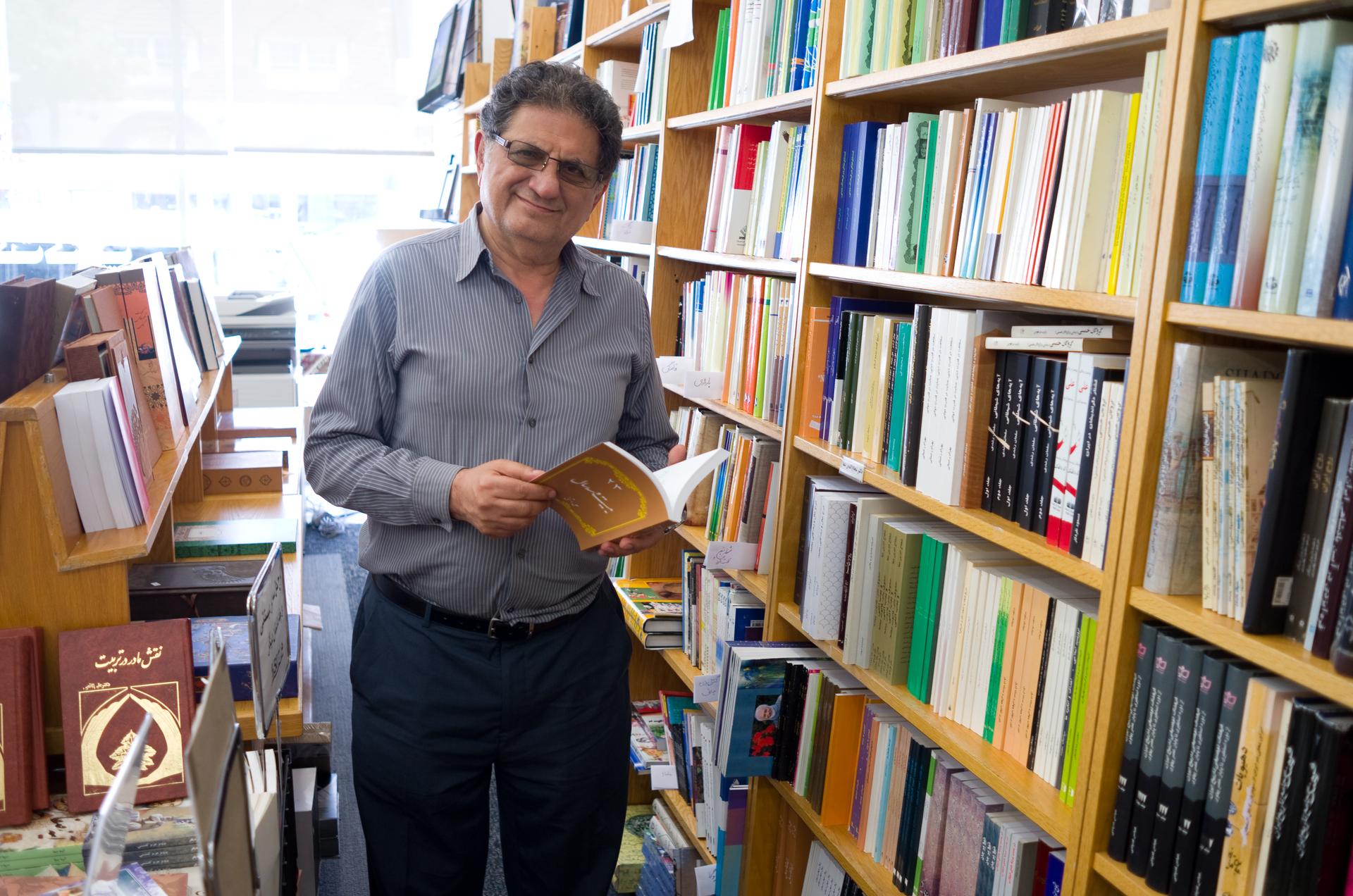

Bijan Khalili owns Ketab Corporation in Los Angeles, which sells and publishes uncensored Persian books that cannot be sold in Iran. “Reading books is a human right,” he says.

Poets are a big deal in Iran, and Forugh Farrokhzad was one of the biggest. In the 1960s, her modern, highly personal work won wide acclaim and brought her the poetry equivalent of rock stardom — she cut records, made films, and even today is known popularly by her first name.

When Farrokhzad was killed in a car crash in 1967, thousands of fans thronged to her funeral. But after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, her work vanished, banned for a decade, and since then heavily censored by the government.

Bijan Khalili knows plenty about Farrokhzad and Iranian censorship. Banned books are a specialty of his. For 36 years he has owned Ketab Corporation, a Persian bookstore in Los Angeles. It started as a simple service to exiles who had fled Iran's revolution, leaving their books behind. But as post-revolutionary censorship took hold in Iran, selling books untouched by Iran's censors became a daily act of defiance.

“Reading books is a human right,” he says.

No book, song or film gets legally published in Iran without permission from Iran's Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Government censors have the power to demand changes or major cuts — or to ban works outright. Among taboo topics are criticism of Islam or Iran's Islamic regime, acknowledging the Holocaust, and interactions between unmarried and unrelated men and women. Kissing and dancing scenes in the Harry Potter books were changed or excised in Iranian editions. Khalili says censors force cookbook writers to remove references to wine, or adapt the recipe for a nonalcoholic ingredient.

George Orwell's “1984” is a book Khalili knows well. When he fled Iran, he took a suitcase stuffed with books, among them the classic Orwell dystopia, as well as books by Dostoevsky, Victor Hugo, and the Persian poets Hafez and Omar Khayyam. In 1981, when Khalili opened Ketab, which means “book” in Persian, his suitcase full of books stocked the store's first shelf.

Today, it's much bigger, but the store on busy Westwood Boulevard, in the Iranian exile neighborhood known as Persian Square, still has an old-time feeling. The spacious, quiet rooms are filled with tall stacks of books on spirituality, sociology, politics, history — there's even a shelf marked “books prohibited in Iran.” And between the stacks, people are reading whatever they want.

For Iranians raised with censorship, it's amazing. Browsing in the business section, I meet Ali, who recently moved to the US from Iran.

“This … just blows your mind, because you do not expect such a thing to be here. You can find the most illegal books in the bookshelves here,” he says.

Ali asked me to use only his first name over fear of retaliation against his family back home — for talking openly with a reporter about books. “If you know more about what's going on around you you will have more knowledge,” he says. “The knowledge is the power.”

If knowledge and power are a tug-of-war in Iran, books are a rope. But Iranian readers are pulling hard on their end, with the help of exiles like Khalili. Because Ketab isn't just a bookstore. It's also one of nearly a dozen Persian publishers outside Iran helping writers bypass censorship to get their books out to the world. (See below for a list of top-selling titles at Ketab Corporation.)

Some writers secretly publish uncensored books inside Iran, but it's risky. Often, writers in Iran will contact publishing houses abroad instead. Iranian readers who can crack the government firewall can access e-books online. There's also a thriving black market in pirated books published abroad.

Khalili says he's pleased his books are smuggled into Iran and reproduced, even if it takes a big bite out of sales. But Khalili is proud of his contribution to the fight against censorship. “I'm proud that I help some Iranian to be knowledgeable about whatever happened, or whatever is close to truth,” he says.

The truth, he believes, could someday set Iran free. “If we are being successful to break that ban, and that censorship, I believe the Islamic regime era will be ended very soon,” he says.

Ending censorship for good still feels a long way off. But Ketab books have reached at least one unexpected bookworm: Iran's government.

Ketab books on taboo topics like gender equality and political prisoners have somehow, mysteriously, made it from Los Angeles to the collection of Iran's National Library.

And who knows? Maybe someone is reading them.

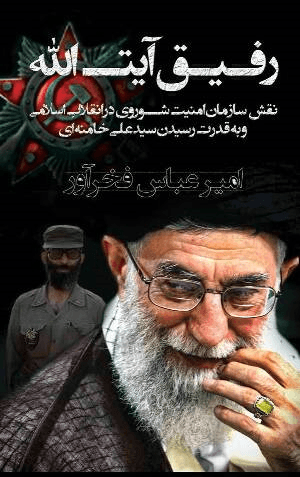

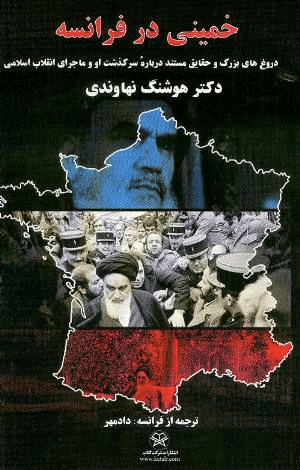

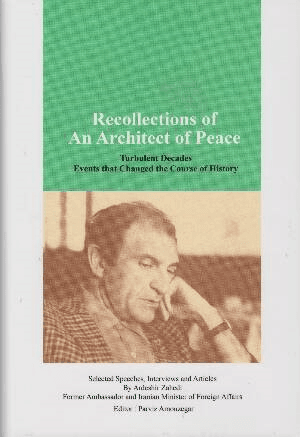

Here is a selection of top-selling titles at Ketab Corporation in Los Angeles: