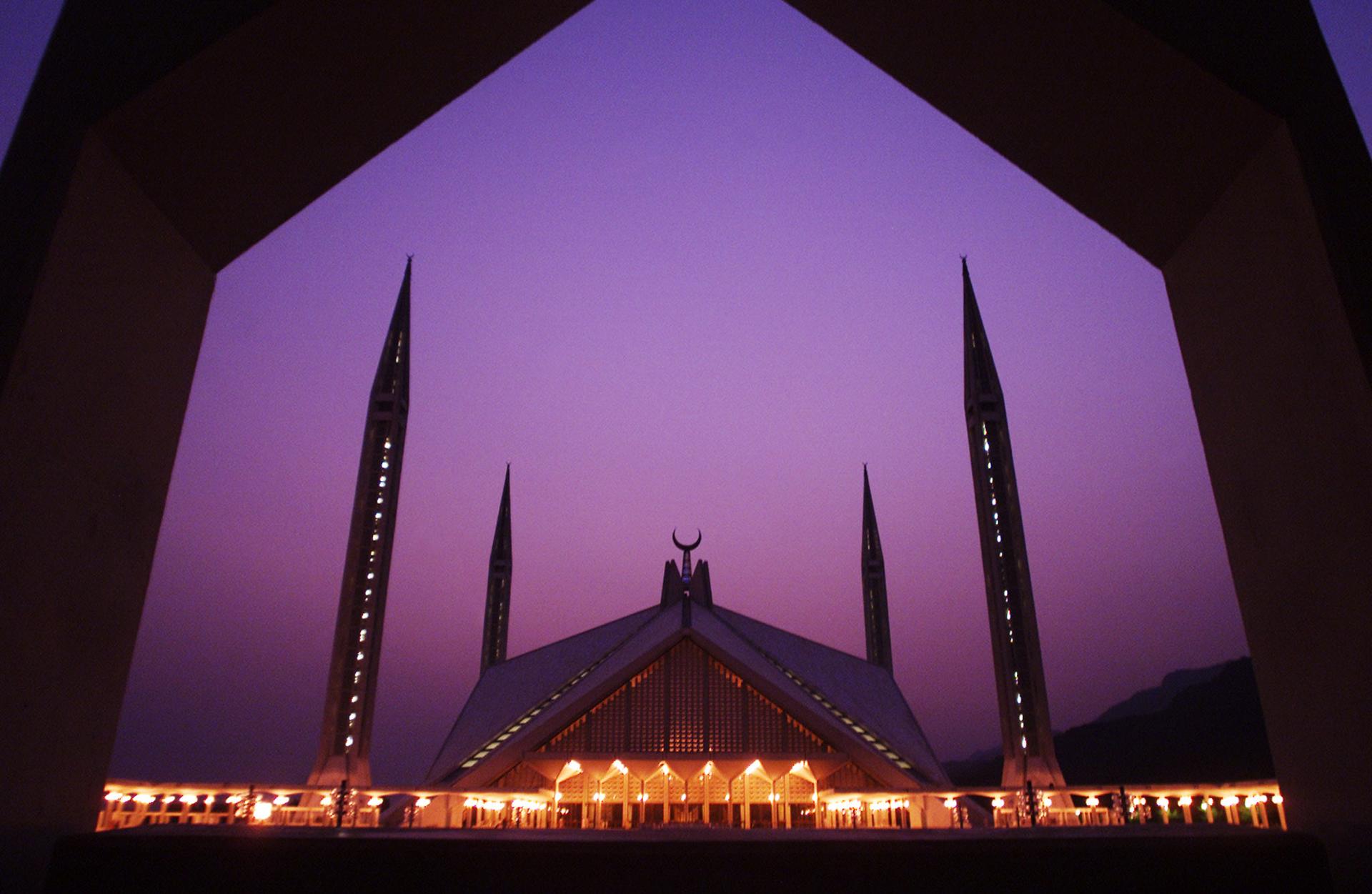

A view of Pakistan's landmark Faisal Mosque at sunset October 8, 2002.

Being an atheist in Pakistan can be life-threatening. But behind closed doors, nonbelievers are getting together to support one another.

How do they survive in a nation where blasphemy carries a death sentence?

Omar, named after one of Islam's most revered caliphs, has rejected the faith of his forefathers. He is one of the founding members of an online group — a meeting point for the atheists of Pakistan.

But even there he must stay on guard. Members use fake identities.

"You have to be careful who you are befriending," he says.

One man contacted Omar to say he had visited his Facebook profile and printed out pictures of him with his family. "You cannot be safe," Omar says.

In Pakistan, posting about atheism online can have serious consequences. Under a recently passed cyber-crime law, it is now illegal to post content online — even in a private forum — that could be deemed blasphemous.

The government took out ads in national newspapers asking members of the public to report any content they believe could constitute blasphemy.

And the law is being enforced. In June this year, in the first case of its kind, Taimoor Raza was sentenced to death for posting blasphemous content on Facebook. As a result, atheists feel their ability to publicly question the existence of God is threatened.

Omar believes the government is at war with atheist bloggers.

"A good friend of mine used to write against religious fundamentalism," he says. "We used to run the [online] group together. I came to know he was very severely tortured. Once you are abducted, there is a high chance your body will come in a bag."

"The state is doing it deliberately, so those remaining get a sign that if you go beyond your limits you will also be facing things like this."

This year, six activists have reportedly been abducted after posting on forums that are pro-atheist and anti-government. One of those activists spoke to the BBC but does not want to be identified. He believes that Pakistan's intelligence service wants to stamp out not only criticism of Islam but also criticism of the state.

In his view, the government is trying to enforce the notion that a good citizen must be a good Muslim.

Pakistan is celebrating its 70th year of independence. Since 1956, it has been an Islamic republic. Many atheists feel the nation is more monolithic than ever before.

In recent years, they say, the Islamic faith has become more visible in public life. Saudi-style dress codes are increasingly enforced. Television evangelists shape pop culture and to be Pakistani is increasingly linked to being a devout Muslim.

Although atheism is not technically illegal in Pakistan, apostasy — refusing to follow or recognize a religious faith — is deemed to be punishable by death in some interpretations of Islam. As a result, speaking publicly can be life-threatening.

Many Pakistani atheists meet at secret, invitation-only gatherings.

The Atheists of Lahore have monthly get-togethers in guarded buildings or private homes. "It's like a secret society," one of those in attendance explains. "It's a bubble where we can talk. It's not all about [renowned critics of organized religion] Richard Dawkins or Sam Harris. We may just talk about how things are going. It's a place where you can let your hair down and truly be yourself."

At these meetups, atheists are predominantly affluent, English-speaking city-dwellers. Money does grant a degree of privilege and protection from those who are hostile toward godlessness. But many self-identified atheists also live in Pakistan's villages.

Zafer was once the muezzin, the man who recited the call to prayer at his village mosque. He used to pray five times a day and was a student of Islamic theology. When he got a job in IT and moved out of his family home, he found his views on religion had changed.

"My family noticed a shift. My mother thought someone had cast a spell on me. I was given holy water to drink and blessed food to eat. She thought it would break the spell," Zafer says.

"These days, I will go along to Friday prayers and celebrate Eid just as a social ritual. My family know I'm not a believer but they give me the space to be myself — as long as I'm not too vocal about being an atheist.

"If you're willing to do certain things — have etiquette, respect your parents and be appropriate in public — you can get away with being a disbeliever."

The Ministry of Information Technology declined my request for an interview, saying the campaign promoting the cyber-crime laws was "simply about raising awareness." They would not comment on the alleged abduction of online activists.

Kunwar Khuldune Shahid is a journalist who has documented the government's response to atheism in the public domain. He believes online atheist activists are being abducted by the government because challenging religion and challenging the state often go hand-in-hand.

"There are two holy cows in Pakistan," he says. "One is the army, the other is Islam. Any person challenging one of these holy cows would, more often than not, be talking about the other as well. The sites whose administrators were abducted were critical of the army and government policy, so blasphemy became a convenient tool."

"In one go, they simply silenced a wide array of critics."

Some of the names in the article have been changed to protect the identity of contributors.

This story was originally published by the BBC's Magazine.