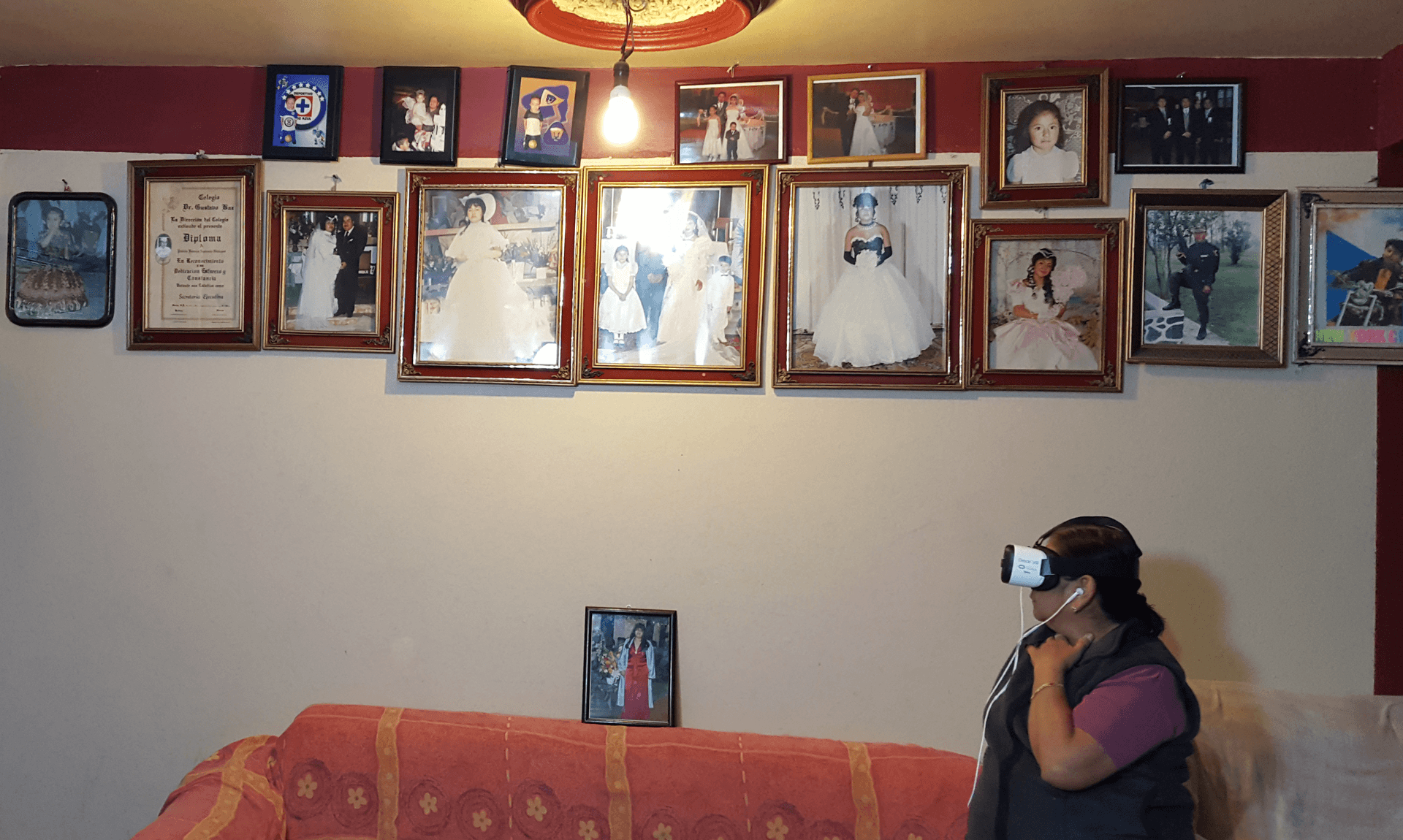

In Mexico City, a grandmother, who has not seen her relatives living in the US for nearly two decades, “visits” them through a virtual reality video made by the Family Reunions Project.

It’s a typical country wedding in Mexico, this one taking place in the town of Poza Redonda, in the state of San Luis Potosí. The bride and groom exchange vows and then things get rowdy with a traditional dance, clapping and flashing lights.

But one person attending the wedding — the bride’s older brother — is thousands of miles away, in his living room in Virginia watching the festivities through virtual reality goggles. He couldn’t make the wedding in person, but the video and 3-D goggles immerse him, letting him look up or down and see and hear everything around him as it was recorded.

But as soon as he takes the goggles off, he’s back in the US.

The video is part of a virtual reality experiment called the Family Reunions Project.

“A lot of people talk about how VR [virtual reality] is cool because it transports you somewhere, or you feel like you’re somewhere else,” says Alvaro Morales, one of the creators of the Family Reunions Project. “But we feel like it’s not being applied toward the communities that could benefit from that transportation the most.”

The project’s creators were in San Francisco recently, showing their project at a conference for immigrant entrepreneurs. Morales says he got the idea for the project when he met the bride’s brother, from the Mexico wedding, in Virginia. He told Morales he couldn’t go to his little sister’s wedding because he was undocumented. If he went to Mexico, he wouldn’t be able to return to the US.

Morales says this is why he’s working with virtual reality — to take people back home, in a way, to places that feel cut off or maybe just too expensive to visit. It might be immigrants in the US who can't go home, or people abroad who can't travel to America.

“They can return to places that they’re effectively barred from returning to, specific spaces, like your home countries, your neighborhood, your school that you went to, the home that you grew up in, and get messages from the people you may be kind of disconnected from, at least in the physical world,” says Morales.

Morales was so excited about the idea, he quit his job as an analyst to work on it with Frisly Soberanis, a video producer. They’re both immigrants, too, who came to the US as kids. Morales is from Peru. Soberanis is from Guatemala.

“This is what this medium is basically made for,” says Soberanis. “Our community is a perfect example of how we could use this medium to bridge gaps and cross borders essentially.”

The first virtual reality “postcards” they produced were for Soberanis’ own parents. His mom, Marleny, lives in New York City, and Soberanis created a video to take her back to Guatemala — to the valleys and fields of her hometown, and to her grandfather’s home. He also recorded her reactions.

When Soberanis’ mom watches the video, wearing the virtual reality goggles, she’s back home, turning to one side, then to another. She looks up and you see the tops of the palm trees, from her childhood. She sees her relatives. Then she takes the goggles off.

“That made me cry,” she says.

She’s sobbing. She hasn’t been back home for 15 years, since she was 25 years old.

“You know, I’d never been to my grandfather’s house?” she says. “And now they showed it to me. I miss that so much. I wish I could be there.”

Then it’s time for Soberanis’ dad to put on the goggles and watch a video of his old childhood friends in Guatemala, catching up on the street in his old neighborhood. They knew he’d watch the video — so, one by one, they reach out to him, to shake his hand, as if he were there too.

“What’s up chaparrito, chiquilín?,” his friends say, using nicknames in Spanish that mean Shorty, or Little Guy. Standing in his living room in New York, Soberanis’ dad reaches out his hand to them, as if he were there, with friends he hasn’t seen for years. When it’s over, he takes off the goggles. He’s smiling.

“Muy bonito,” he says. Lovely. His smile fades though. He fixes his gaze down at the floor. He’s quiet for a while.

Soberanis is a bit surprised by the reaction — he didn’t realize how hard these videos would hit his parents.

“I didn’t realize how much he was missing,” says Soberanis. “I didn’t realize how much pain migration is, obviously because I grew up here, and my friends are here. Half of his life was in Guatemala. So for me to be able to see that he missed it a lot was a very intense experience for me and also for him.”

Last winter, Morales, the other creator of the videos, traveled to Peru and Mexico to record more 360-degree videos. He went to family dinners, toured different neighborhoods, elementary schools, all places that immigrants in the US had asked him to record.

“To bring them back to places that you have this deep connection to but you almost forgot what it looked like, to be able to see which walls were painted, how you think things may look much smaller or how people have grown or aged,” says Morales.

Meanwhile, back home in New York, Soberanis helped people produce their own videos, or “virtual reality postcards” for their family members, which he would then send to Morales.

“So sometimes I would show up with a postcard, [and say] ‘Hey, here, spend some time in New York and get to see grandchildren you may have not seen in twenty years,’” says Morales.

Morales knew the project would be emotional. It’s beyond seeing photos on Facebook or calling relatives over Skype. He says he wasn’t prepared for how people would react when they put on the goggles and stepped into a virtual reality postcard.

“A lot of people would talk back to virtual characters,” says Morales. “They would go for the hugs. Even though they understood that it was not a live stream, that it had been prerecorded. That completely took me aback.”

Now, Morales and Soberanis are creating a documentary about their experience. They say they're clear that virtual reality doesn’t take away the pain of family separation — it just brings that pain to light.

“It can be a really joyful experience, but then it turns sour,” says Morales, “because virtual reality has a good way of highlighting the distance and the cruelty, the fact that his parents, or a grandma in Mexico, can only see their relatives through these kind of silly goggles on their face.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?