A Czech town renowned for its history of anti-Semitism would like to forget its Jewish past

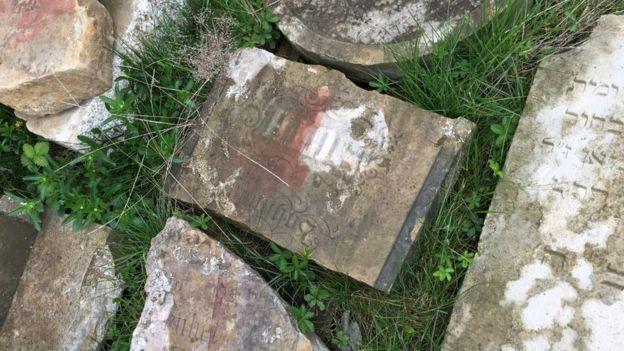

This tombstone was discovered in someone's cellar, where it had most likely been since the Jewish community was deported and murdered in World War II.

Plans to rehabilitate a pre-war Jewish cemetery in the Czech town of Prostejov have run into fierce local opposition. The foundation behind the plan says it has been torpedoed by deliberate misinformation and anti-Semitism.

Tomas Jelinek stands over a broken headstone and scrapes at patches of cement obscuring the name. Sweating heavily in spite of the chilly afternoon, he brushes away the last patches and squints at the inscription.

"Herlitzka," he decides. "Bernhard Herlitzka. Died… April 1879. I can't make out the date."

There's not much more to go on. The broken tombstone lies face up in the grass, with perhaps a dozen or so more beside it, some whole, others in fragments. The inscriptions are a mixture of German and Hebrew. "Beloved daughter…" begins one. "Here lies…" reads another. The rest is lost.

"We can find the story of a person," says Tomas Jelinek, formerly head of Prague's Jewish community.

"We have the files of the Chevra Kadisha — the Jewish burial society, where we can find the position of the graves, the text that was on the gravestone and so on."

"We usually try to contact the relatives. We sometimes find direct heirs," he adds. "They're surprised, touched. Some of them are really excited."

So far Jelinek has recovered 34 headstones in and around Prostejov. He has just loaded this one and a dozen more into a trailer at a nearby village, hence the sweating.

"The whole cellar was made from them. They weren't hard to find," the villager tells me. He says he'd rather not give his name.

"I'm just returning what should never have been taken."

A town 'renowned for anti-Semitism'

Every few months, says Jelinek, someone from Prostejov will call him to say they've found a stone with Hebrew writing propping up a chicken coop or lying at the bottom of the garden.

One family discovered their entire back yard was paved with marble tombstones. Unfortunately, they have been reluctant to part with them.

Related: The rescued Jewish tombstones of Thessaloniki

"Prostejov had a very bad history in the relationship to the Jews. It was famous for its anti-Semitism in the 19th century," he tells me.

"And it's still in the population. You can hear it on the street, and you can also see that they just reinvent things which people thought would disappear for ever after the Second World War."

For centuries Prostejov was an important center of Jewish life in Moravia, producing a number of influential rabbis. In 1942, that history came to an abrupt end, when the town's Jews were deported by the Nazis.

The following year, Prostejov's ethnic German mayor bought the town's old Jewish cemetery from the Reich authorities. It contained the graves of 1,924 people; the last burial had been in 1908. The tombstones were marked with crosses; high quality marble was sold; lesser quality softer stone was handed out free to locals.

After the war, the site stayed empty for years. People remember playing there as children. They told their parents they were going to play "na zidaku" — down at the Jews' place. Some remember unearthing bones.

Anger, lies and opposition

Today, it is a small park, bordered by houses and a school. But 74 years after its desecration, plans to rehabilitate it have caused uproar.

"I think the mayor pretty much summed it up when she said the rights of the living must take precedence over the rights of the dead," Deputy Mayor Zdenek Fiser told me at Prostejov's splendid town hall.

He was referring to one of many stormy public meetings held in the town on a proposal put forward by the US foundation Jelinek now represents — Kolel Damesek Eliezer. The foundation wants to demarcate the old cemetery with a knee-high hedge and place some of the recovered tombstones there.

But after a petition signed by 3,000 locals the town council quickly withdrew its support. A visualization was attached to the petition, falsely showing the park surrounded by a brick wall.

"The thing is, there are only a few descendants of people of Jewish origin left here in Prostejov," Fiser told me, explaining the overwhelming opposition to the plan, which would involve rerouting several paths leading to the school.

"Most of the people who signed the petition live opposite the park or are parents of kids who go to the school. So most people who signed the petition against it actually live there."

He also dismisses Tomas Jelinek's claims that Prostejov was a hotbed of anti-Semitism.

"You're asking me about anti-Semitic articles in the local press, but we didn't write those articles, did we? As you well know, journalists need controversy, a 'cause celebre,' to make their articles interesting," Fiser explained.

"If they'd just written about plans to turn a local park into a place of remembrance, no-one would be interested. But put 'anti-Semitism' in the headline, and all of a sudden everyone's up in arms."

For now, Bernhard Herlitzka's tombstone is being stored with the rest at Prostejov's New Jewish Cemetery, a short drive out of town. It is a provisional arrangement, until the foundation and the town council can agree what to do with the old one.

Judging by the atmosphere in Prostejov, it could be some time.

Broken gravestones — then and now

There's a post-script to my visit. I'm given a guided tour by a local historian who's researched Prostejov's Jewish community. She takes me down a little alley between a cluster of buildings.

"That was the main synagogue. That was the reform one. And that was the yeshiva," she says. The synagogues are now churches; one Catholic, one Protestant. The yeshiva is now where you go to pay your parking fines.

Finally, we end up at the Old Jewish Cemetery — the park that the Jewish community still regards as a burial ground. Shouting teenagers rush past us in groups. Mothers push prams. A small black monument faces the school.

She takes me a few meters further to a second monument, a plexiglass replica of the tombstone of Prostejov's most famous rabbi, Zvi Horowitz.

"Oh," she exclaims.

The plexiglass has been snapped in two. Half of it is lying in the grass. I make sympathetic noises to hide her evident embarrassment. It has clearly just happened.

I take a photo and show it to Deputy Mayor Fiser. I ask him who he thinks could have been responsible.

"I don't know," he replies, peering at my phone.

"Perhaps it was the wind?"

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?