Trees in the US are migrating. What it means for the future of large forests.

Forests in the Eastern US are typically made up of diverse tree species, including both evergreen and deciduous trees. But the unnaturally rapid pace of tree species heading north and west could fragment these unique communities.

As the planet warms, many tree species in the eastern US are migrating.

Pines and spruce are heading north, while oaks and maples are heading west of their historical ranges, according to a recent study. In all, the newly published research confirms, 86 tree species in the eastern US are moving into new areas.

Trees don't just pick up and move, of course. Their seeds tend to spread in one direction or another, depending on local conditions, and saplings will have more success in places best suited to their natural traits.

“[But] we are not only talking about the addition of the new seedlings,” says Songlin Fei, an associate professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University and the study’s lead author. “We are also talking about mortality that is happening to the big trees, especially given the drought that we have in the Southeast.”

“On average, these trees have shifted about 15 kilometers, or roughly 10 miles, per decade,” Fei says. “[That’s] close to 50 kilometers during the [30-year] study period.”

To illustrate how this occurs, Fei says, imagine a line of people stretching from Indianapolis to Atlanta. “Every individual in that line has not moved a single inch, but there are more people joining the line, say, in Indianapolis or in Lexington, and there are people dropping out of the line in Atlanta. What’s going to happen is the center of this line will seem to have shifted,” he explains.

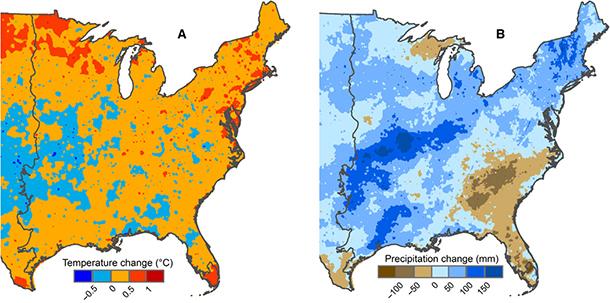

This shift is due both to warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns caused by climate change, Fei says. Broad-leafed trees, such as oaks, maples and hickories are moving westward due to changes in moisture, while trees in the evergreen group, such as pines, spruce and firs, are moving northward because of temperature changes.

The western portion of the study area, states like Missouri and Illinois, have had more precipitation in the past 30 years compared to historical averages. The broad-leafed trees can take advantage of increased moisture in a relatively dry area. In other words, they can be pioneers in places that were previously too dry for them.

Historically, trees have frequently shifted their range, Fei says, mostly due to the effects of glaciation or the retreat of glaciers. He points to studies that have tracked the movement of trees in New England — movement that was also driven by changing temperatures and precipitation. The difference, he says, is that those studies examined the movement of trees over thousands of years. Fei’s study looked at only a 30-year period, from 1985 to 2015.

The changes Fei has tracked would have happened over several thousand years, had nature taken its normal course and not been affected by changes in the climate due to human activity.

Still unknown is to what degree the rapid movement of trees will change the ecological balance within large forest systems.

"In the current study, we are looking at individual trees. A forest is a composition of multiple species, which, in ecological terms, we call a 'community,'" Fei explains. "So, we don't know whether the community is currently vulnerable to breakdown because of the different directions of this shift by individual species."

“We are interested in looking at how these communities are responding as a group. Are there certain community groups that are more vulnerable than others? This is what we are really interested in looking at next,” Fei says.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.