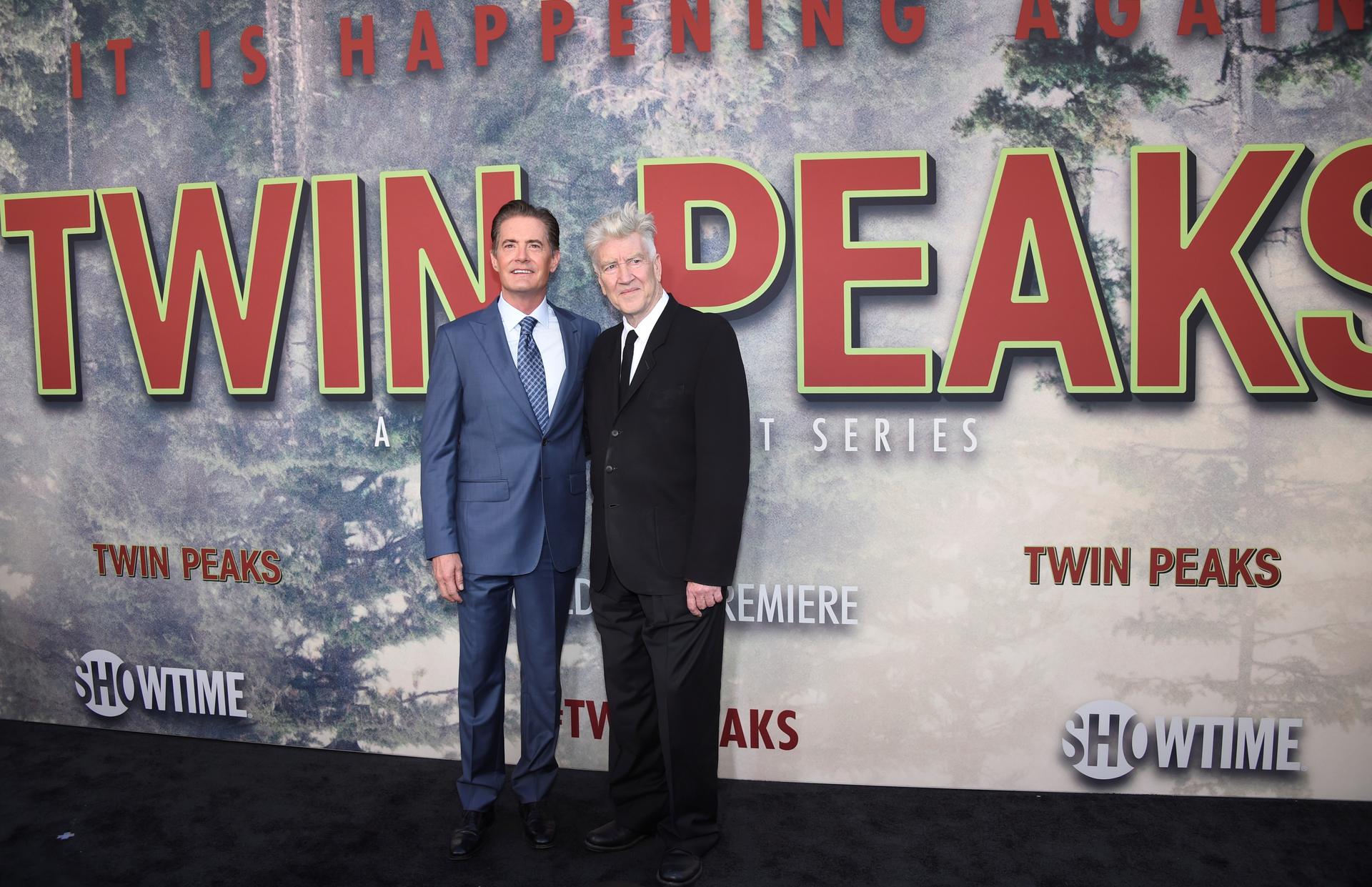

Kyle MacLachlan, left, and David Lynch attend the premiere of "Twin Peaks" in Los Angeles, May 19, 2017.

With David Lynch’s “Twin Peaks” having returned for a third season after a 27-year wait, the post-Soviet world is taking the time to reminisce. The original show gained a cult following in countries like Russia and Ukraine — a seemingly counterintuitive obsession.

But in the chaotic years that followed the fall of the Soviet Union, the terrific oddness of “Twin Peaks” ended up appealing to local viewers. Novaya Gazeta, a then-young newspaper in Russia, even had a team of dedicated “TV detectives” decoding both the plot and the meaning of the show. Critics compared the show’s popularity to an “epidemic” and popular reader surveys of the time asked audiences everything from which characters they could fall in love with to which ones they sincerely pitied.

Today, magazines like Russian Elle appeal to collective nostalgia by placing characters like Lara Flynn Boyle’s Donna Hayward on lists like “1990s TV Heroines Whom We Want to Look Like.”

Much like American critics, Russian critics are taking note of the fact that the third season of “Twin Peaks” is different — altogether darker, stranger and wilder than the original. As Buro 24/7, a trendy fashion and culture portal started by Russian socialite Miroslava Duma recently argued, the third season does not try to cash in on any sense of sentimentality but is itself its own terrifying but riveting adventure. Perhaps most importantly, the third season does not try to be a crime show and occasional soap opera, and its humor, occasionally harsh in the first season especially, is now harsh all of the time.

The third season’s deep, multidimensional darkness is, perhaps, just as relevant to life in modern Russia as the original two seasons were, especially due to the fact that modern Russia is pretty much the inventor of political unreality, as argued by writer Peter Pomerantsev. Though it is most commonly associated with Russian information warfare tactics — one where the truth is expendable and infinitely malleable — it would be unwise to assume that unreality is simply something Russia exports in order to sow confusion abroad.

Just a week of watching Russian state television makes it obvious that Russian viewers have long been taught that facts don’t matter. But it’s not just the issue of Russian TV peddling lies — it’s an issue of casting a spell over the audience, certainly something surrealist David Lynch knows a thing or two about. And based on everything we’ve seen in the third season so far, it has become obvious that Lynch wants readers to know they are being messed with, to let them in on the joke, or at least make them uncomfortable enough so that they may seriously question what is happening on the screen.

Much like the plotlines in “Twin Peaks” itself, the plotline of modern Russian history is hard and, at times, frightening to follow. That’s why it's wise to have clues and guides along the way.

Viewing Russia through the prism of the Lynchian aesthetic (if this term hasn’t yet been coined, we should go ahead and coin it now) is particularly useful these days. And the new “Twin Peaks,” in particular, is just absurd enough, just violent enough and just hypnotic enough.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?