How private donors are making college dreams a reality for undocumented immigrants

Mariana Hernandez greets Christian Brothers University President John Smarrelli Jr. at her May 13, 2017 graduation in Memphis, Tennessee. She is among the first nine graduates of the Latino Student Success program, specifically designed for students brought to the country illegally as children or on visas that later expired.

Mariana Hernandez wore a wreath of artificial flowers around her graduation cap, an homage to the late artist Frida Kahlo. Then she walked onto the stage, shook hands with her college president and became the first member of her immediate family to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Several factors helped her make it to this point — her own persistence and the support of family and friends. But she was also the beneficiary of a scholarship program that’s specifically designed for students who may be in the country without authorization.

The 22-year-old was one of the first nine graduates from the Latino Student Success program at Christian Brothers University, a small Catholic institution in Memphis, Tennessee.

Her graduation on Saturday reflects a broader trend: private institutions and private donors across the US are stepping up to assist students with immigration issues who may be shut out of public universities. Her graduation also shows how, amid uncertainty about the future of immigration and of immigrants living in the US, a significant number of immigrant families are continuing their lives as usual.

Hernandez was brought to the US from Mexico on a visa that later expired, landing her in a legal gray zone. Through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) program, she was able to get a Social Security card and a renewable, two-year work permit. Now, she can work anywhere.

Her immediate plan: Apple.

She started work at a Memphis-area retail outlet for the electronics giant in college, and plans to continue. But she’d like to use her international business degree to work for one of Memphis’ big institutions, like St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, AutoZone or FedEx.

President Donald Trump has said during his campaign that he would end the Obama-era DACA program, although he later softened his stance. Still, at least one DACA holder has been deported, and others are in federal custody.

“That’s kind of like my ghost following me around,” Hernandez says. “I want to be able to pursue all these things, but not knowing if I’ll be able to even with this college degree, that’s scary.”

Still, she feels prepared for post-college life. She said she benefitted from strong relationships with professors and the chance to learn leadership skills on the small campus.

Her parents are Mexican immigrants who encouraged her to go farther than they had. Her mother finished ninth grade and couldn’t continue. Her father made it as far as grade 12. In 2013, she finished high school near the top of her class. College, though, would be harder. State universities in Tennessee do not recognize DACA status. Bills to change the law have failed several times in the Tennessee legislature, including again this year. Critics of the bill argued it would draw unauthorized immigrants to Tennessee. The bill's repeated failure means students like Hernandez — and many of her classmates who were brought here illegally — had to pay the far higher out-of-state tuition rate.

Also: In the age of Trump, fewer lenders want to provide this med student with student loans

Hernandez’s dream school, Christian Brothers, was too expensive for her to afford. She spent her first year at a community college, when an anonymous donor put money into a new scholarship program at Christian Brothers specifically designed for students who had been brought to this country illegally as children or on visas that later expired.

In 2014, Christian Brothers admitted 14 freshmen and 11 transfer students, including Hernandez. Another anonymous donation of $3.6 million later expanded the program, funding an additional 80 scholarships. The program has since won federal recognition — college president John Smarrelli Jr. and student Franklin Paz Arita traveled to the White House in 2015 to meet then-President Barack Obama during a celebration of efforts to promote Hispanic education.

Many other private institutions across the US, such as Emory University in Atlanta, Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and small colleges in Appalachia are recruiting undocumented students. And in some states, students with unclear immigration status still qualify for in-state tuition so long as they reside in the state. In Texas, for instance, a law passed in 2001 allowed these students to receive in-state tuition and state financial aid. Most of the money available nationally is privately raised, and students with DACA or no immigration status at all are ineligible for Pell Grants and other federal aid available to citizens.

Christian Brothers has since joined the national organization TheDream.Us, which works with various partner colleges to offer scholarships to undocumented students.

Next year, 31 freshmen and 11 transfer students from outside Tennessee will be coming to Christian Brothers through TheDream.Us, receiving scholarships that cover full tuition, room and board. That’s in addition to a new cohort of 20 students who have scholarships from Latino Student Success. The combined recipients will make up a substantial proportion of the total incoming freshman class of about 350.

Anne Kenworthy, vice president for enrollment, says these private scholarships fit into the college’s broader mission of uplifting the community. “We're educators. So we're all better off if our neighbors are educated.”

Students like Hernandez have jumped into campus life and led student organizations. "They've been given this opportunity and they're not going to miss out on anything," Kenworthy says.

But she acknowledges some ongoing challenges. Many of the students with immigration problems have family obligations that prompt them to earn money outside of school, and that can cut into study and homework time.

Hernandez’s path to graduation wasn’t easy — she had to balance work, study and family obligations, including taking care of her younger brother. “What helped me get through the stress, as clichéd as it sounds, was my family and my friends, for sure,” she says.

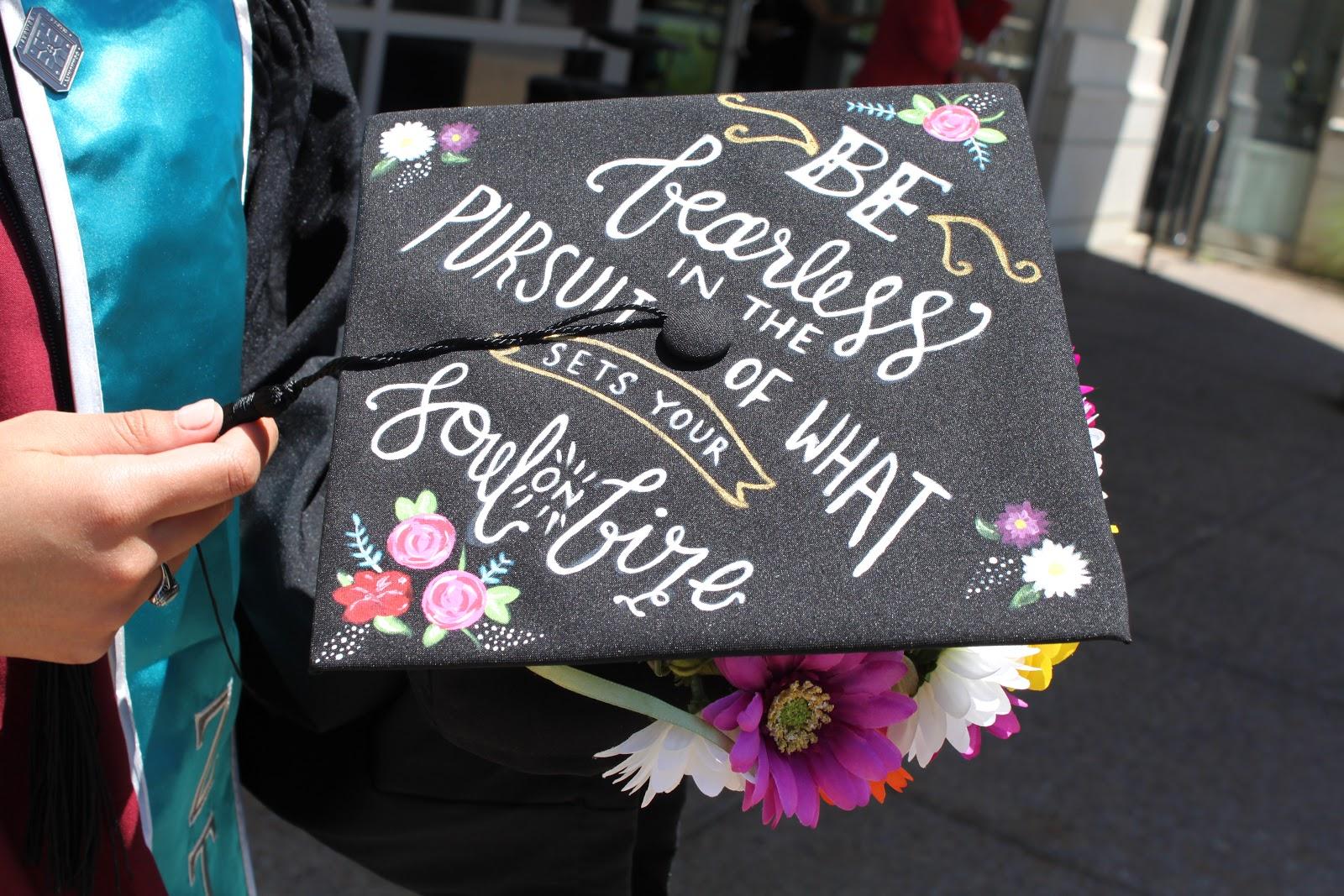

Her graduation ceremony Saturday lasted several hours. Afterward, she showed off a quote her boyfriend painted on the top of her cap: “Be fearless in the pursuit of what sets your soul on fire.”

She’s hopeful that public support and encouragement will help more undocumented students nationwide do exactly that.

Journalist Daniel Connolly first interviewed Mariana Hernandez when she was 17 and about to begin her final year of high school. Her story and those of other children of immigrants are included in his recent work The Book of Isaias: A Child of Hispanic immigrants seeks his own America.