Pooja Roy (L), child of a sex worker comforts Rani Dey, child of another sex worker at Soma Home in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata July 14, 2007.

The numbers are depressing: Every 8 minutes a girl goes missing in India. Most of these girls are trafficked for sex, beggary or domestic labor.

Unofficial counts put the number of victims of sex trafficking in India at 16 million — not counting the girls from neighboring Nepal and Bangladesh who end up here. Mumbai, where I live, is the second-most frequent destination for these girls.

The stories are heartbreaking: In very rare cases the girls have run away or are kidnapped. But in most cases, according to Priti Patkar, who has run an anti-trafficking NGO in Mumbai for 30 years, almost all of are taken by people they trust — promised a job or marriage.

“Stranger danger is a myth. These girls are preyed upon, they’re carefully profiled by traffickers with a full measure of their desperate straits,” Patkar says.

Some, like this 16-year-old who calls herself Panshi, though that isn't her real name, are inducted into the sex trade by their own families.

Stuck in a strange place

Once they’re sold into brothels, there are slim chances of breaking out. Some girls do, though.

“One girl who is with us now, she’s 15, came from Bangladesh to Mumbai to be a film actor,” says Patkar. The girl signed a contract, and someone even deposited money in her account. And then her agent started bringing different men to her room and she was forced to have sex with them.

“She had no idea she’d been trafficked until there was a police raid and she found her agent had been charging all the men and had made a tidy packet off her,” Patkar says.

If the girls are rescued, a lot of state and NGO machinery gets involved — there are police raids and rescues, and then the state’s Child Welfare Committee has to figure out where the girls should go.

Sometimes the families are so poor, they don’t want them back; they have too many mouths to feed, which is why the girl was sent in the first place.

Sometimes the families are so poor, they don’t want them back; they have too many mouths to feed, which is why the girl was sent in the first place.

Other times, the girls don’t want to return. There are even cases where little girls don’t even know where they are from.

So what do you do if you can’t go home? If you’re lucky, you wind up Patkar’s shelter for trafficked girls.

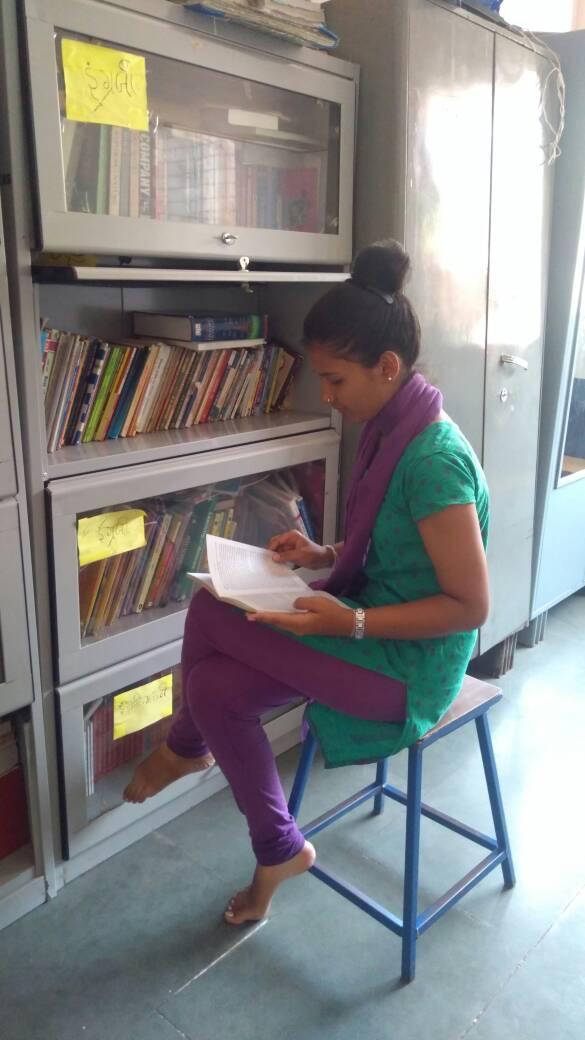

The word naunihal means a sapling, and that’s the name of this special home for girls run by Patkar, just outside Mumbai city. This is where I met the teenage Panshi. As Patkar says, “She’s definitely unusual. She basically rescued herself.”

The family business

Panshi is a slim, pretty, girl with long, braided hair. She meets me in a simple salwar-kameez, tunic and pleated pants, to keep her cool in the heat. Though it’s a Saturday, she’s just come back from extra classes.

She tells me she has been in the shelter since September 2015. She grew up in the greater Mumbai area, about an hour outside the city. She lived with her mother, younger sister and younger brother. She also had an older sister who was married and worked.

She excelled in school, but when she was 13, her family made her drop out. They said they couldn’t afford it. She met an 18-year-old boy, a “friend” who envisioned a better life for her. He met her parents, tried to persuade them to let her study, told them he’d marry her. She’s not sure why they didn’t like him, but she was packed off to her father’s village, in a different state “as punishment,” she said.

She was miserable. She missed her “friend,” she missed school. Eventually, her aunts said they’d let her return to the city if she joined the family business.

The family business for their tribe, the Bedias-Bancharas, is prostitution, which is practiced openly. The men in the families pimp their wives and sisters; the women earn the money. Panshi’s family has branched out to the city. Her mother is a sex worker in Mumbai and her older sister is a “dance bar girl.” Dance bars are the Indian version of a low-end gentlemen’s club, without the nudity, usually havens for trafficking and abuse.

Panshi, 14 at the time and unsure what was involved and desperate to get her life back, agreed. She would do what her cousins did.

“I was just pretending to agree to the conditions,” she says. But they did what they said and she was brought back to the city — to an aunt’s apartment, not to her old home.

“Then out of the blue, my mother and sister took me to a mall for shopping, and then dinner. For a change! Then suddenly, I was taken to my aunt’s house and while my mother and aunt stood outside the door, this person came to the room,” she says. “I begged this person to let me go, to let me go meet my friend. But he’d paid money … he didn’t want to waste it.”

Her mother and aunts were right outside the door. They could hear her pleas and screams as she was initiated into the sex trade. Over the next 10 days, she was forced to have sex repeatedly. But nobody intervened until she fell violently sick. Her older sister took her home.

She was afraid to contact her “friend,” afraid he’d reject her because of what had happened to her. Eventually, he contacted her and insisted she tell him why she was avoiding him.

“He cried a lot and finally said I fell in love with you and not your body, I don’t care what’s happened to you,” Panshi recalls.

Her mother and aunts were right outside the door. They could hear her pleas and screams as she was initiated into the sex trade.

Panshi ran away with him and for almost a year, they lived together as a couple. But her family had filed a police complaint against him for kidnapping a minor. When Panshi heard, she acted.

“I went to the police station and told them my family did this to me, and that’s why I’m with him and want to stay with him.” Then she pauses and says softly. “It was a big mistake, actually”

Learning to live again

Because she's a minor, the state wouldn’t let her return to her boyfriend. And the Child Welfare Committee concluded that sending her home was risky, she’d probably wind up back in the sex trade. For the sixth time in two years, Panshi was in a new home, this time at the Naunihal shelter.

Some girls take a long time to adjust to life at the home, says Patkar. And post-traumatic stress can show up even in the most resilient girls. They have a girl who started having panic attacks a year after she got there. The attacks were so bad, she’s back in counseling and is being home schooled.

For the first two months, Panshi tells me with a big smile, all she did was cry.

Patkar says some girls at the shelter feel a huge push and pull from their families. It’s almost like Stockholm syndrome: it’s hard to hate or stay angry with the people who betrayed you when you are supposed to love them.

“Panshi’s family visits often, they really try to persuade her to return to them, telling her she can study now,” says Patkar. But she’s “strong, self-driven, diligent, focused, knows what exactly she wants and she’s a child who doesn’t live in the past, who wants to work on her present so that her future looks like she wants it to look like.”

“Whatever happens, happens for the good,” Panshi told her family. “If I hadn’t come here, I wouldn’t have these opportunities.”

“Whatever happens, happens for the good,” Panshi told her family. “If I hadn’t come here, I wouldn’t have these opportunities.”

No child can just walk out of the home. The Child Welfare Committee has to do a risk assessment as well as decide if the girl is capable of supporting herself.

Panshi is in school after a three-year gap. At the home, she has learned to make beautiful jewelry, which she sells; the money she makes goes into a bank account she can’t access until she’s 18. But she laughs and says she won’t touch it even then.

A brighter future

“I have a goal,” she says, voice ringing with confidence. “I want to definitely finish my graduation and then work. I want to be financially independent.”

She’s just started articulating another dream: to pursue a master’s degree in social work so she can work with the kids in her tribe, rescue them from prostitution.

And, she wants to take care of her family. She still feels responsible for her siblings and her aging mother.

Patkar’s NGO Prerana, which means inspiration in Hindi, doesn’t just run the shelter home, but also has many programs to steer children away from prostitution. Patkar says that since 1986, the NGO has ensured not a single one has entered the sex trade. “We track the girls for about two years,” she says, “and so far, at least as far as we know, they’re all safe.”

Success stories abound: Some alumna have married and started families, others have jobs; many stay in touch.

At Naunihal, all the girls have a “Care Plan” which Patkar describes as a self-directed plan of action — whether it’s vocational or, for the little ones, something as simple as “I want to see my mother only once a month.”

This year, Panshi is learning English. “This is my plan for 2017. I have a sharp mind and I want to be fluent.”

Then she adds: “What I decide in my mind, I do it. And when I have problems, I face them and solve them so they don’t come back. For me, I’m enough. I have to rely on myself.”

This is part a deep look by Across Women's Lives at sex trafficking around the world. From India to Italy, Uganda to the UK, we'll look at the toll the toll that being sex-trafficked takes and some of the strategies taken by women to escape. Check back from now through Friday for more of our coverage of the journey out of trafficking.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?