Taiwan may be one remarkable democracy

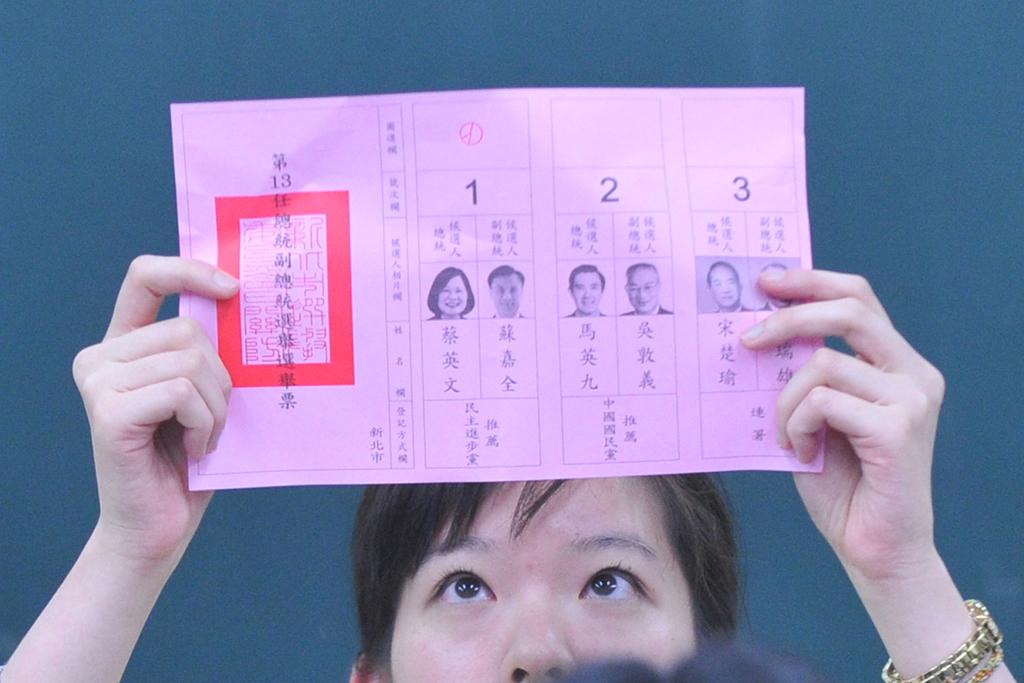

A election worker counts the ballots for presidential candidates in Taipei on Jan. 14, 2012.

TAIPEI, Taiwan — Pundits often point to Turkey or Indonesia as a model for the Arab Spring's transitional democracies.

In Asia, some urge the increasingly reform-minded Burma to follow the example of Taiwan, an erstwhile dictatorship that has become a regional poster child for functioning democracy.

Others aren't so convinced.

“Each country's transition process is just too unique," said Dafyyd Fell, deputy director of Taiwan studies at the University of London.

"In Taiwan's case there are some positives [to use as examples], such as electoral debate leading to real policy improvements, and the relationship between democracy and the combating of political corruption,” he said. But that doesn't mean they will work for another country.

There are many aspects of Taiwan's democracy that appeal to struggling states, but experts say that Taiwan's progress is idiosyncratic, and warn others from drawing too many parallels from one successful transition to systems that are still in their infancy.

More from GlobalPost: Taiwan's elections going down to the wire

This diplomatically-toisolated island 110 miles off China's southern coast, which wrapped up its fifth free presidential elections earlier this month, has been lauded as one of the 20th century's great democratic success stories.

Voter turnout in the election, which saw incumbent President Ma Ying-jeou win a second term, was about 75 percent. There were no reports of violence and the process was reported to be largely fair and completely free by European and US observers.

It's a far cry from 1988, when Taiwan ended nearly 40 years of martial law and was still operating as a virtual one-party police state.

Ruled by a nationalist Kuomintang party that fled to the island in 1949 after losing a bitter civil war to Mao Zedong's Communist forces, the KMT introduced itself to the Taiwanese by embarking on a decades long campaign known as “White Terror.” An estimated 30,000 were killed and thousands more were either imprisoned or simply went missing.

More from GlobalPost: Is Taiwan Asia's model democracy?

Back then Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, who was derisively referred to as Cash-My-Check in Western diplomatic circles at the time, was viewed by the US as an important ally against the spread of Communism and given a free hand to rule with an iron fist. Ironically, Chiang was staunchly anti-democratic, believing that only authoritarian systems could work within Chinese societies.

Today, Taiwan rivals Japan and South Korea as Asia's most vibrant and stable democracy, and is often used as a political touchstone for the fledgling democracy aspirations of China's rights activists. In the wake of successful elections this month, mainlanders jealously clamored for their government to work as smoothly as Taiwan's.

“If we look at Taiwan compared to its Asian counterparts, then it performs extremely well. For instance, its female political representation and improvement of gender rights is quite impressive and ahead of Japan or South Korea. Similarly, its party system is much more stable and institutionalized than those two cases,” said Dafyyd.

The island's democratic credentials are indeed impressive: the military and police have undergone substantial reforms; civil institutions, human rights and education systems have been strengthened; the electorate is passionate about social justice and its hard-won freedoms.

But that doesn't mean what worked for Taiwan pertains to other countries.

In Taiwan's case, there was a custom-built road map and a timetable in place, according to George Tsai, vice president of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, a government-run body which works to increase democracy within Asia.

“The civil institutions function extremely well, and after five general elections we are moving steeply towards a maturing democracy. We are in very good shape,” said Tsai.

“But it really was important to have solid economic growth followed by a strengthening of the middle class and a good educational system. Civil society and judicial reforms followed suit. That was the model we used, and it worked well for us,” he said.

Tsai says that Taiwan's sustained economic growth, broadening of the middle class and education were the cornerstones of the transition. From there, the island's politicians were able to dismantle many of the authoritarian legacies of the past, such as martial law, the one-party state and rigid restrictions on movement and association. Further legislative reforms freed up other areas such as the judiciary, military, electorate and media until the island was ready to hold its first free presidential elections in 1996.

Tsai stresses that Taiwan's experience was gradual, and a large measure of its success came from the buffer that economic benefits were providing Taiwanese at the time, a situation that is unlikely to play out in Burma, not to mention many of the Arab Spring countries.

Although resource rich, Burma's economy, once one of Asia's strongest, is now the region's second smallest. Its infrastructure and education and health systems are in tatters and wealth is unevenly distributed. Those problems, coupled with the country's systemic disregard for human rights and ongoing military operations against a number of its ethnic groups, paint a very different picture to Taiwan's experience during the '90s.

The message is simple: cookie-cutter models that take superficial similarities into account and disregard the myriad historical, political and cultural realities on the ground aren't likely to succeed.

Some analysts point to Turkey's handling of its Kurdish problem as a worrying sign for its Arab Spring model claims.

Indonesia's rampant corruption, vote buying, poor human rights record, and the fact that all three presidential tickets in the 2009 election included former generals under late dictator Suharto, have raised concerns that the world's most populous Muslim country and newest member of the G20 is not as far along as it should be.

And while South Korea and Taiwan share former military-backed autocracies with Burma, the similarities largely end there.

“If China transplanted the US model of democracy, it would collapse overnight. We cannot impose one system onto others,” said Tsai, who also lectures at Taipei's Chinese Culture University.

“If you look at Indonesia or the Philippines, they are very liberal democracies but are wracked with corruption and economic development is skewered so the middle class is not expanding as it should. It puts the kibosh on political and democratic development.”

Although Taiwan's electorate is deeply divided between north and south, rich and poor, and whether the island should lean towards independence or further integration with its old foe across the Taiwan Strait, democracy has actually worked to stabilize the country as voters have punished extremist politicians at the ballot box, and rewarded more centrist leaders.

What makes Taiwan's path toward democracy all the more remarkable is that the country got there largely unaided.

The sort of incentives offered by the West to reforming and transitional countries were never dangled in front of Taiwan. Its diplomatic isolation and most countries' acceptance of a "One-China Policy" left the island locked out of bodies such as the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Asia Development Bank.

Despite its impressive economic development and its democratic efforts, this country of 23 million is still without representation in most world bodies, has very few diplomatic allies and even fewer free trade agreements — despite being one of the world's largest trading countries.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?