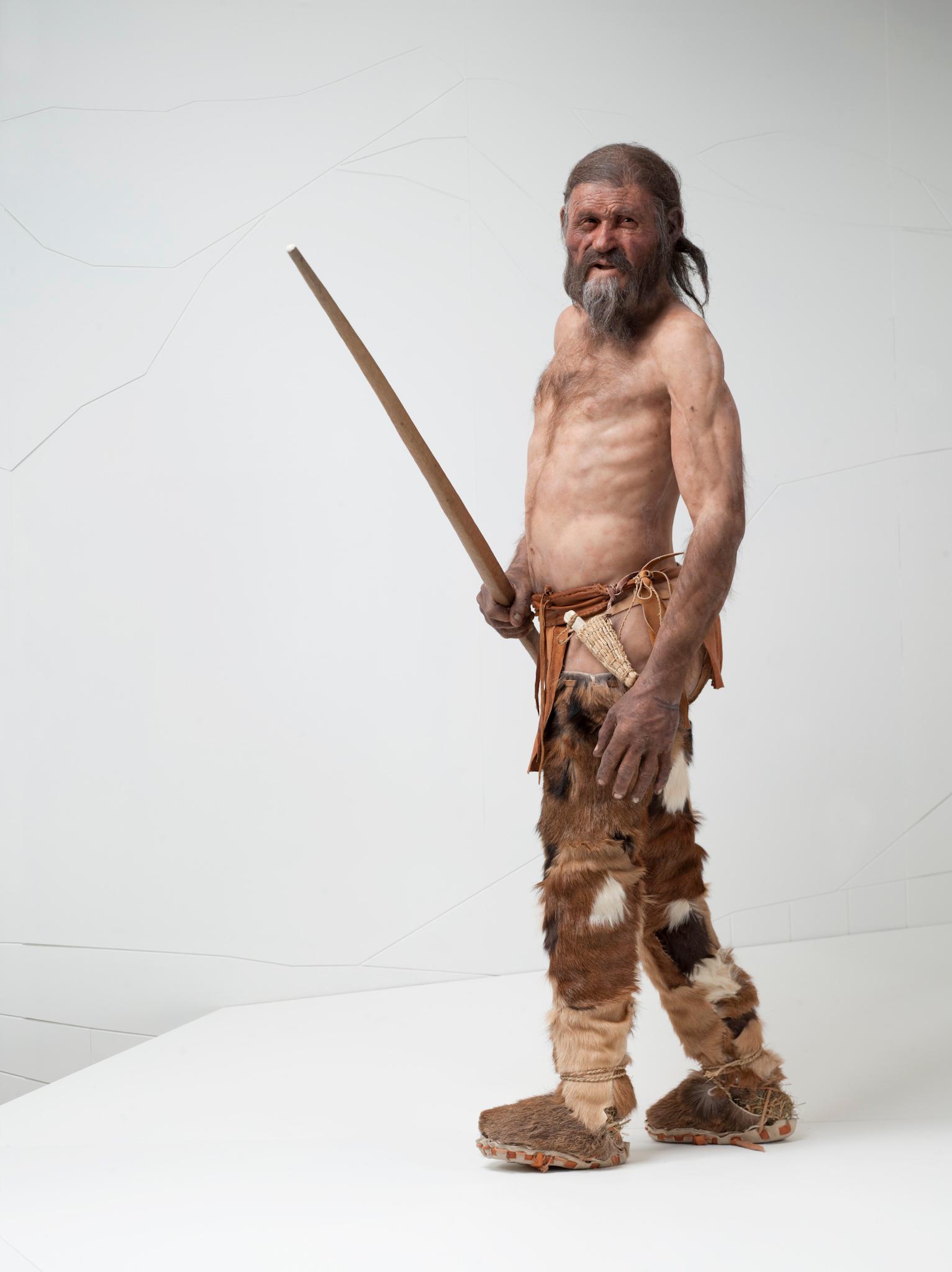

Ötzi the Iceman at the finding place.

There’s a lot of mystery surrounding Ötzi the Iceman, Europe's oldest natural mummy. The best guess is that 5,300 years ago, Ötzi was crossing an alpine ridge in the Italian Alps, where he was murdered and his body preserved in the ice.

His frozen corpse was discovered accidentally by hikers back in 1991, along with his clothing and equipment, on the Schnalstal/Val Senales Valley glacier. The 5,300-year-old mummy was so well-preserved that scientists have been able to piece together — gradually — a compelling picture of how he lived, and his equally fascinating death.

Let’s start with the premise that Ötzi was murdered. An arrowhead was discovered in his left shoulder, but what does it tell us about the circumstances surrounding the crime?

“The cause of death is most likely due to an arrow that hit him in the left shoulder blade and caused massive bleeding,” says Chief Inspector Alexander Horn of the Munich Criminal Investigation Department.

Horn was part of a team tasked by the South Tyrol Museum to answer the question: Who killed the Iceman? The investigators included archaeologists as well as experts from forensic medicine, radiology and anthropology.

The challenge for this modern-day Sherlock Holmes was to use criminal investigation techniques to establish a narrative about a corpse that’s been frozen for 5,300 years.

There were no witnesses to the crime, at least none that Horn could interrogate. But by examining how deeply the arrow head penetrated the Iceman’s body, Horn was able to deduce that the arrow was shot from behind from quite a distance, about 30 meters or so, and likely surprised the victim. He reasons that if Ötzi was shot at close proximity, the energy would have caused the arrowhead to travel into his back and to exit. Instead it remains lodged near the shoulder blade.

But it was the Iceman’s right hand that helped Horn imagine how the crime went down. It shows signs of being badly injured with what Horn calls a “defense wound.”

“One or two days before the murder, there was a fight. Ötzi was part of that fight and he managed to defend himself, grabbing a sharp object like a knife. He had a massive injury to the right hand,” Horn says.

Horn says that wound shows signs of earlier healing. “So therefore [the fatal blow] looks like a continuation.” From a behavioral perspective, Horn says taking aim at Ötzi from far away suggests that the killer “might have learned from a physical, direct fight one to two days before, which didn’t go well, so the decision was made to kill and shoot from a distance.”

That kind of violent escalation is very familiar to modern criminal investigators. “Usually it doesn’t start with a murder. There is other violence before. If you look at Ötzi’s case, you have conflict, which is not just a verbal conflict, it is violence. He had to defend himself, and then you see the next step, which is ‘I’m going to follow this man and although he’s already injured, I’m going to attack him from a distance, because this man is obviously dangerous, a strong man and he will fight back.”

The crime may have happened long, long ago, but “it is interesting,” says Horn, “because you still see those kinds of behaviors nowadays in homicide cases. … I don’t think they have changed over the past 5,000 years, because it’s always the same: we have motives of revenge, anger, and strong emotions of hate.”

To find out more about Ötzi, the glacier mummy from the Copper Age, pay a visit to the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!