Convicted scammer creates federal PACs from prison

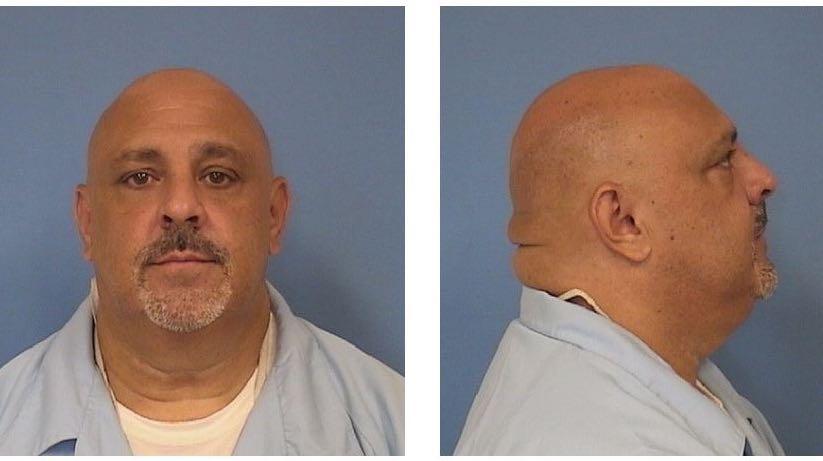

Inmate Angelo Pesce created a PAC from prison.

Angelo Pesce is serving a 10-year prison sentence in Illinois for “theft by deception.” While behind bars, he’s barred from voting.

But that hasn’t stopped Pesce from apparently creating “Impeach the Assole” — a crudely named federal political action committee formed last week to raise political campaign cash — and another dubbed “Angelo Pesce Defends Pedophiles.”

No federal law prevents Pesce from forming a PAC or soliciting money for it. And he doesn’t have to tell unsuspecting donors he’s an inmate at Taylorville Correctional Center, having scammed a woman out of nearly $100,000.

Pesce’s situation is the latest reminder of a nagging problem with political committees: While most PACs follow the rules, there are few safeguards against hucksters looking to make a buck.

With some PACs, “people donating think it’s a legitimate organization, but sometimes the creators take your money and run,” said Brett Kappel, a Washington, DC, campaign finance lawyer.

“There is no rule that a PAC is barred from buying a boat and riding off into the sunset,” added Brendan Fischer, associate counsel at the Campaign Legal Center.

As a practical matter, that makes it close to impossible for a misled political donor to recover his or her money.

A message the Center for Public Integrity sent to an email address Pesce provided in paperwork filed with the Federal Election Commission was not returned. The prison where he’s an inmate doesn’t allow reporters to contact inmates by phone unless they appear on a preapproved list.

Creating a federal political committee is relatively simple: just fill out a few forms and submit them to the FEC.

It isn’t clear from Pesce’s FEC paperwork whether he meant to create a traditional PAC, which may give limited amounts of money directly to political candidates’ campaigns, or a super PAC, which may raise unlimited amounts of money to independently promote political campaigns. Pesce won’t be required to reveal until midsummer whether his PACs have raised and spent any cash.

Either way, this is at least the second political group created by an inmate in as many years.

Two years ago, the Center for Public Integrity reported that Adam Savader, a former political volunteer who had been convicted of cyberstalking and extortion, created a super PAC named Second Chance PAC. Savader’s super PAC ultimately reported raising no money.

Then there’s the curious case of Cary Lee Peterson, a self-styled “congressional lobbyist and election campaign guru” whose purportedly pro-Bernie Sanders super PAC seemingly scammed dozens of donors out of tens of thousands of dollars.

Among those donors: “James Bond” actor Daniel Craig, who in 2015 gave $47,300 to Peterson’s “Americans Socially United” super PAC, which has repeatedly ignored the FEC’s requests to comply with federal campaign finance disclosure laws.

The FEC has fined Peterson’s PAC, and agency officials confirmed Tuesday that this fine remains unpaid. There’s little evidence indicating Peterson’s PAC used more than a token amount of the money it raised to promote Sanders’ bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. Where the rest of the money it raised went remains a mystery.

And last year, the FBI arrested Peterson on unrelated criminal fraud charges related to his business ventures. The Securities and Exchange Commission also has a civil complaint pending against Peterson alleging multiple counts of securities fraud.

Some government officials have attempted to address these so-called “scam PACs” — groups that solicit money using the names of candidates but then spend little or no money on politics.

For example, the oft-gridlocked FEC, whose commissioners agree on almost nothing, have nevertheless been united in asking Congress for more authority to deal with scam PACs.

But to date, Congress has ignored the FEC’s requests.

Unscrupulous PACs could continue to hoodwink less sophisticated donors, commissioners and campaign finance experts say, as efforts to tighten PAC rules and increase oversight have so far failed.

In other words, the FEC can’t really do much to shut down these groups, even if they do have the mailing address of a state prison, as is the case with Pesce’s PAC.

In 2004, Pesce stole $93,534 from a woman by falsely presenting himself as a commodities trader, according to a DuPage County, Illinois, press release. Pesce pleaded guilty to theft by deception but fled before he was sentenced in absentia to 10 years in prison.

Police arrested Pesce in 2014. He began serving his sentence in Taylorville in 2015, according to Illinois Department of Corrections records.

Illinois Department of Corrections spokeswoman Nicole Wilson said inmates are permitted to receive money electronically. And while Illinois corrections law prohibits inmates from “engaging in an unauthorized business venture,” it’s silent on the specific issue of inmates forming political committees.

Pesce “would be wholly responsible for complying with any laws and regulations governing political action committees,” Wilson said.

One potential problem for Pesce: the banking address he lists for one of his PACs does not correspond to that of a bank at all. Instead, it’s a Motel 6 in suburban Chicago.

The FEC forms he submitted included a notice that PAC filings with “false, erroneous, or incomplete information” are subject to civil and/or criminal penalties.

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative news organization in Washington, DC.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!