A Muslim immigrant and a Christian pastor find common ground — and try to connect with their Latino neighbors too

Abdul Taleb and Dan Schmitz have been neighbors in East Oakland for a long time. Now they’re trying to get to know — and help — many of the other people in their community.

Abdul Taleb has run Mi Carnal market for 12 years. It’s a corner grocery store on busy Foothill Boulevard in East Oakland. People in this low-income neighborhood, known as the San Antonio district, stop in to buy fresh mangoes or cuts of meat.

In this neighborhood, where 42 percent of the residents are foreign-born according to the latest available Census estimates, customers might come from Mexico, Guatemala or Cambodia. East Oakland, the 94601 zip code, is nearly half Latino, 20 percent black and 20 percent Asian. One of Taleb’s customers is Dan Schmitz, who for nearly 30 years has lived in the Oak Park apartments, just a five-minute walk from Mi Carnal.

“I’ve known and shared meals with Abdul for a long time,” says Schmitz. “That’s just part of the nature of the neighborhood.”

The two men often engage in the kind of chitchat that usually takes place between a shopkeeper and a customer: the weather or the price of milk. And it might have stayed that way, had it not been for Donald Trump winning the presidential election last November. Only after the election did both Schmitz and Taleb realize how much immigration policy factored into their spiritual callings.

Taleb himself is an immigrant; he came to America at age five. His grandfather was the trailblazer of the family, leaving Yemen for the US in the 1970s. The older Taleb first worked as a farmhand in Fresno, and eventually moved to Oakland where he opened a pair of Mi Carnal grocery stores. These are the stores Abdul Taleb now runs.

“I grew up in the neighborhood,” Taleb explains. “I have managed to learn the Spanish language very well so I can communicate with a lot of my customers and friends.”

Schmitz watched Taleb grow up. He came to the neighborhood in 1989 to volunteer with a Christian charity. Now, Schmitz is the lead pastor of the New Hope Covenant Church, located just a few blocks away from Mi Carnal market.

After the election of President Trump, anxiety was high. The Public Policy Institute of California estimates 10 percent of people in the city of Oakland are undocumented.

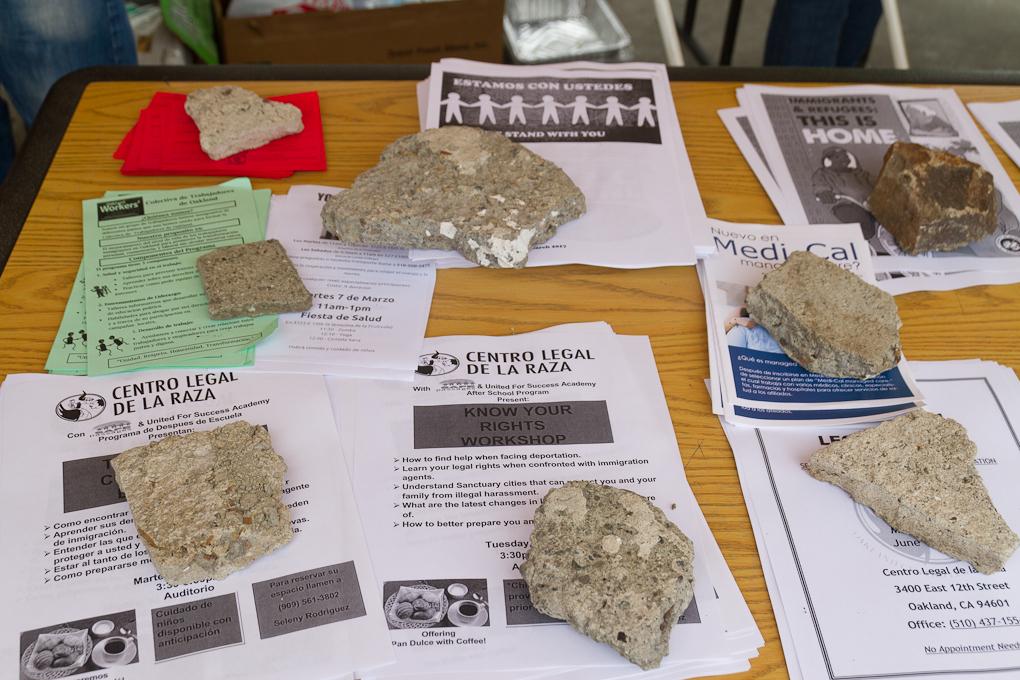

By Christmas, Schmitz and his congregation — mostly college educated whites and Asians — felt they had to offer their neighbors more than holiday goodwill. So they set up a table in front of one of Taleb’s Mi Carnal markets, handing out gift bags and “know your rights” flyers in both English and Spanish about what to do if you are questioned by immigration agents.

Like many of Oakland’s small grocery owners, Taleb is Muslim. He talked to Schmitz about organizing a bigger, interfaith immigration fair. Even though Taleb is from Yemen — one of the countries excluded under President Donald Trump’s now-halted immigration ban — he is more concerned about his Latino neighbors than his own situation.

“They are more vulnerable to executive action,” says Taleb, adding that Muslim immigrants tend to come from the Middle East or Asia and are more likely to have visas or refugee status. Data collected by the Migration Policy Institute bears this out. “They have some kind of paperwork so they can stand up for themselves. When it comes to the Latino community, it’s a whole different issue. Their lives can be changed in a split second.”

Schmitz knows that as a white man and US citizen, he doesn’t face the risks some of his neighbors do. But he believes there are common elements between the Christian and Muslim teachings.

“We recognize that we have in our primary stories that we are refugees, that we are to care for refugees,” says Schmitz. “I feel kindred with Abdul as he reaches out to the neighborhood and feels their vulnerability. We ourselves aren’t necessarily vulnerable, but that doesn’t mean that we’re not connected to what’s happening.”

For Taleb, interfaith friendships are a way of fighting back against stereotypes about Muslims.

“The biggest misconceptions are that they’re violent people, but that’s not true,” he says.

Schmitz and his congregation also want to show that not all Christians are in lockstep with Trump and his immigration policies. A Pew Research analysis of exit poll data estimates that 81 percent of white evangelical Christians voted for Trump.

So, on the first Saturday in March, Taleb closed off the parking lot of his store.

Volunteers set up information booths, barbecued chicken, grilled pupusas, and fried corndogs — and gave everything away for free. Young boys kicked a soccer ball in the parking lot, while toddlers took turns in a bounce house. Schmitz and Taleb mingled with about 150 people in the crowd, which included the neighborhood’s city councilmember, an Oakland police liaison and former Oakland mayor Jean Quan.

Organizers guessed that perhaps it was simply the cold, drizzly weather that kept people inside. Schmitz thought too that maybe the flyers handed out in the neighborhood and posted on storefronts weren’t enough to advertise the event.

And while attendance has increased since similar immigrants rights events in the fall, there are real fears amongst Latinos to be seen in public spaces this way.

“We’ve seen a definite increase in the community of children afraid to go to school because they’re afraid parents will be taken, people who are afraid to receive medical services, or report crimes to police,” says Eleni Wolfe-Roubatis, an attorney who heads up immigration services for Centro Legal de la Raza, a non-profit organization providing legal counsel to low-income immigrants.

More: Fear of immigration raids? This Honduran woman says she would cross the border again.

But this likely won’t be the last event that brings together different groups. Centro Legal is part of the newly formed Alameda County Immigration Legal and Education Partnership, which includes nine community and government organizations serving black, Latino and Asian populations.

Wolfe-Roubatis has not seen this level of partnership in her 12 years representing immigrants in Oakland, “I think it’s had a real impact on the immigrant community as a whole to feel solidarity and united,” she says.

While the white Christian minister and the Yemeni Muslim business owner aren’t planning another outreach event yet, this wasn’t their first action of solidarity and probably won’t be their last.

Schmitz and other members of New Hope eventually sued Oak Park’s landlords for the squalid conditions at the apartment building. Schmitz has lived there since the 1990s and his neighbors are mostly low-income Latino and Southeast Asian immigrants. Their legal triumph is chronicled in Valerie Soe’s 2010 documentary The Oak Park Story and in Russell Jeung’s 2016 memoir, “At Home in Exile.”

Taleb regularly volunteers with the interfaith group Genesis by visiting Christian churches to answer questions about Islam. Both men know that friendships — and change — take time.

“I think it’s events like these and when you live together that breaks down barriers,” says Taleb.

Also: How a Buddhist shrine transformed a neighborhood in Oakland