The new carry-on device ban is reportedly about al-Qaeda and ISIS bombs

Laptops and other devices larger than cellphones are banned for direct US- and UK-bound flights from certain airports.

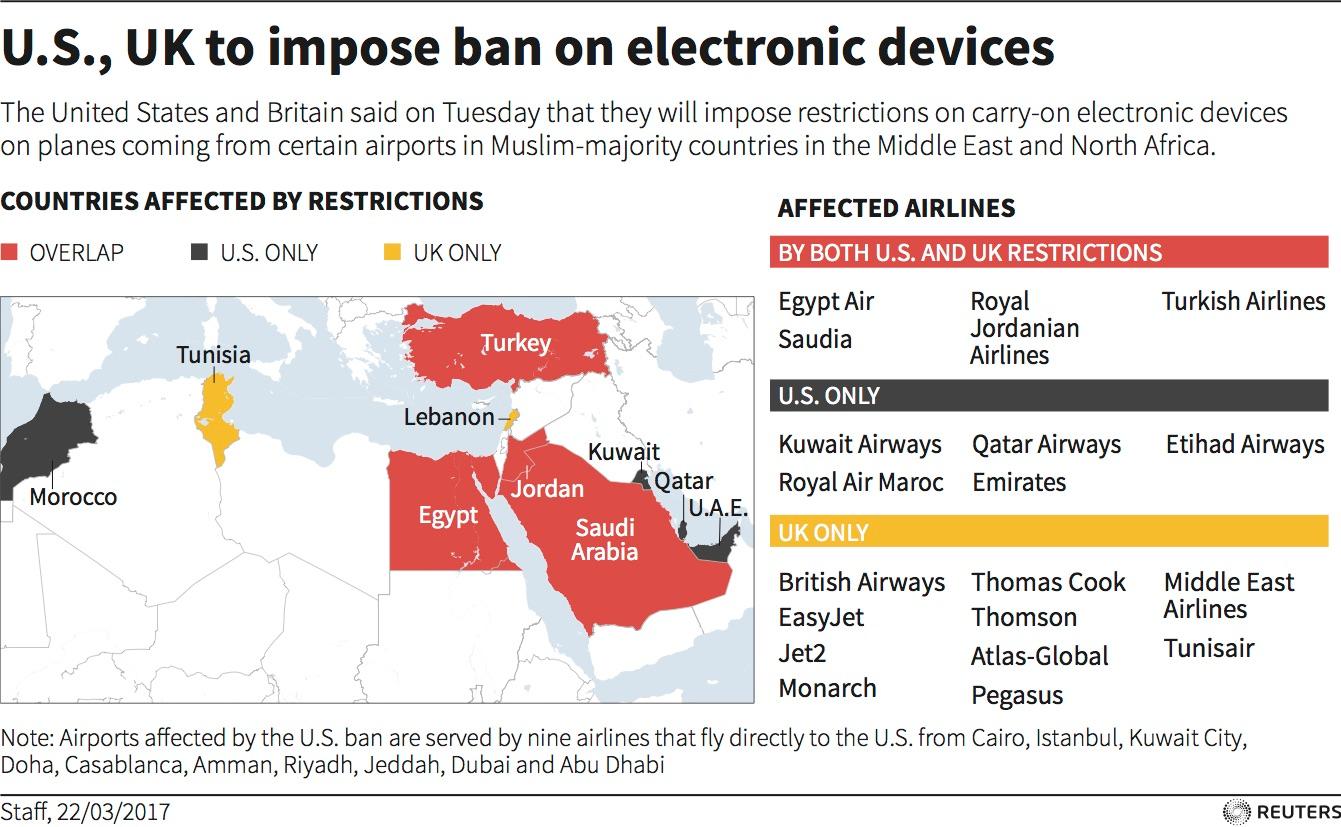

On Tuesday, US authorities ordered a ban on laptop computers, tablets, cameras and other items larger than cellphones in passenger cabins of direct US-bound flights from certain airports in the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, Egypt, Turkey, and Jordan.

Britain imposed similar restrictions on flights from six countries, while France and Canada said they were considering their own measures.

Analysts say an intelligence tip was likely behind the announcement. The New York Times reported that US counterterrorism officials have intelligence that ISIS operatives are developing a bomb to be hidden in laptop computer batteries.

Doing so would bring the group up to the technological level of rival al-Qaeda's Yemen branch al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, or AQAP, where so-called expert bomb maker Ibrahim al-Asiri has spent years on a similar effort.

Related: Laptop, tablet bans on flights: Here's what we know

Airport security is much better than just a few years ago, Jay Ahern, the former acting director of the US Customs and Border Control, told AFP.

"But clearly terror organizations continue to target air travel, and they have shown a clear ability to innovate," Ahern said.

'Innovative' AQAP bombmaker

Recent attacks on aircraft in Somalia and Egypt are evidence of a focus by jihadist groups on developing harder-to-detect bombs — and getting them on flights.

The bomb that blew a hole in the fuselage of a Somalian airline in February 2016, killing one person, is believed to have been built into a laptop computer carried into the passenger cabin.

That attack was claimed by the al-Shabaab group, which has links both to Al-Qaeda and IS.

And Moscow authorities have blamed a cabin-based bomb for destroying an October 2015 Russian charter flight from Sharm el-Sheikh that killed 217 people. The Islamic State claimed it smuggled a bomb on board in a soda can.

Security services are particularly focused on Asiri, the explosives mastermind of AQAP.

Asiri is believed to be behind the placement of explosive-packed printer cartridges discovered on cargo aircraft headed toward the United States in 2010.

He is also tied to the failed underwear bomb AQAP deployed hoping to bring down a US aircraft in 2009.

"He was very innovative," said Frank Cilluffo, director of the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security at George Washington University.

"Clearly the question is how many disciples he has taught, and whether AQAP has spread its tentacles into Syria," where the Islamic State is based, Cilluffo said.

CAT scan equipment

The US carry-on electronics ban creates a new layer of inconvenience to travelers, but security experts said forcing electronics through checked baggage screening is indeed safer.

In advanced airports, cargo going into a plane's hold is screened by computed tomography or CT machines like those used for CAT scans in hospitals, said Nik Karnik, a senior director at Morpho Detection, a leading producer of CT explosive-detection machines for airports.

They are much better than the traditional x-ray machines at boarding checkpoints, Karnik explained.

Rather than viewing a bag from one angle, CT machines create a 360-degree image. They are "looking at both mass and density, trying to determine if it fits within a range of threats that we are looking for," he said.

The CT machines' detection algorithms are also regularly updated based on constant contact with aviation security authorities on new threats, he added.

CT machines though have yet to be designed for boarding checkpoints in the airport, making it more secure to put suspect items like computers in checked baggage.

"The goal is to bring CT technology to the checkpoint so you don't have to take your laptop out of you bag," said Karnik.

Jeffrey Price, an aviation security expert at the Metropolitan State University of Denver in Colorado, said that forcing a possible bomb into the hold also reduces the attacker's chance of success.

"It introduces more room for error to add a timing device [if the plane were delayed, the bomb would detonate on the ground], or a barometric trigger switch," he told AFP in an email.

"In either case, rough baggage handling may also trigger or render useless the device. [There is] more assurance of the thing detonating if you are holding it and command-detonate it."

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!