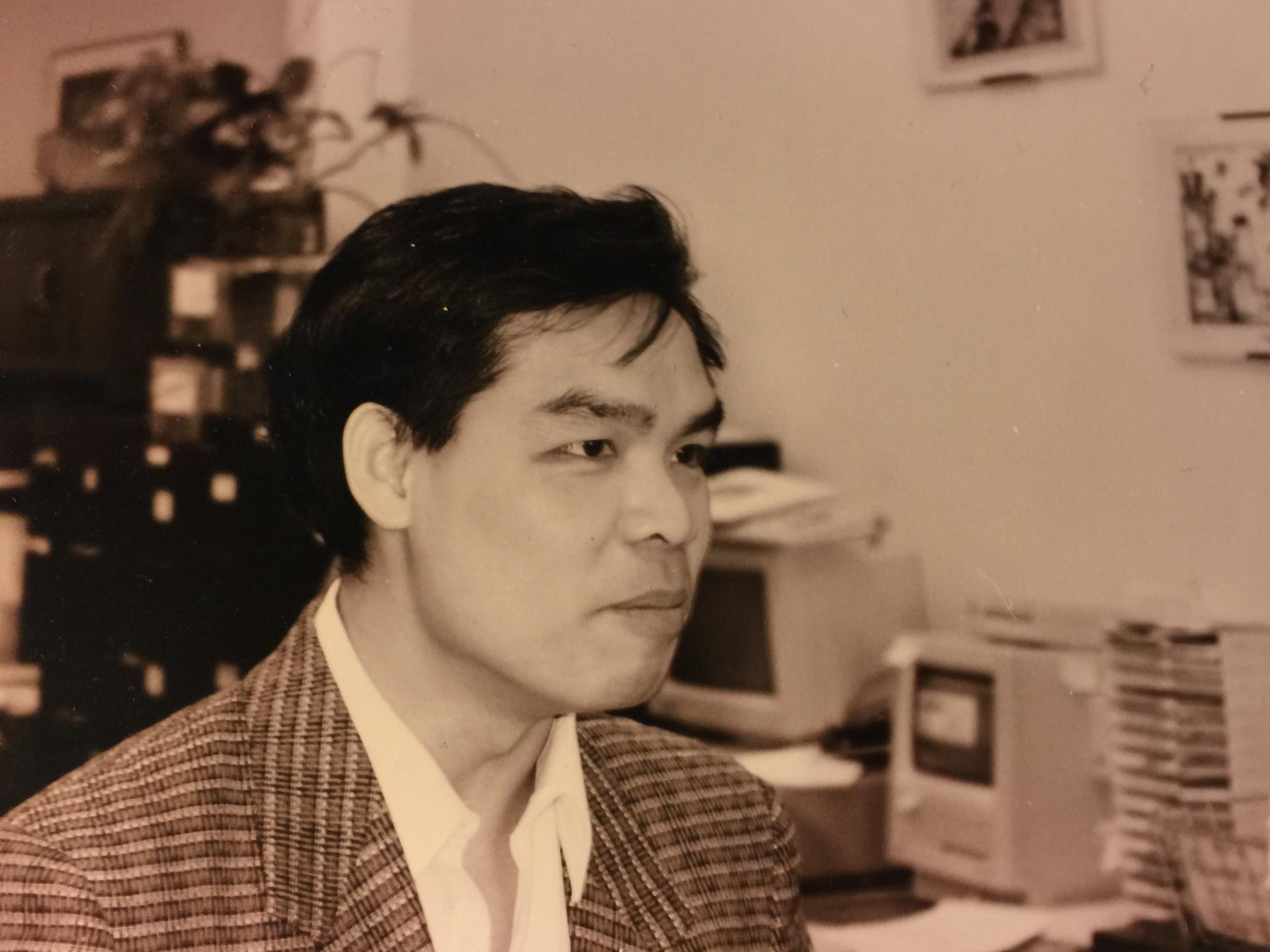

Andrew Lam joined Pacific News Service in 1990. Their second office on Market Street in San Francisco — the first was destroyed in a 1989 earthquake — is where he became a journalist. Pacific News Service and New America Media will close their doors on Nov. 30, 2017.

Back in 1988, I was a graduate student in creative writing at San Francisco State University. I took a class called “The Art of the Memoir” — or something along those lines — and for it I had to write three pages to explain why I wanted to become a writer.

I struggled. With a biochemistry degree from UC Berkeley and English as my third language, I wasn’t confident about my writing, to say the least. But explaining why I wanted to write was easier than convincing myself that I could: I wanted to tell the story of my people. Refugees suffering under the radar, the grief of losing a country, the pains of exile, the crisis of not belonging or of displacement. I wanted to give words to my memories of the Vietnam War and my experience as a child refugee.

Little did I know that the first essay I wrote in my first semester at San Francisco State would make its way to the hands of Sandy Close and Franz Schurmann, the husband and wife team of editors who ran Pacific News Service. I got a phone call. Sandy asked if I wanted to have tea. Then she wanted to know if I wanted to come to the Monday editorial meeting. And then she wanted to hear my opinions about refugees and boat people.

I was perplexed. I barely knew how to write. I was in school to learn that skill. Isn’t it kind of early? And why me? Besides, I didn’t read newspapers regularly. I couldn’t find Israel and Egypt on the map, let alone consider myself a journalist.

Sandy wasn’t to be deterred.

“We read your essay. Your voice is what is needed.”

I tried not to laugh out loud.

After all, this was 1989. And the media had rarely bothered asking what Vietnamese Americans had to say about the Vietnam War. In the movies, we wore black pajamas and conical hats. We got shot. We served as the background against which Americans cried mea culpa. In the news, we were seen as victims, as drowning boat people. No one I knew was making a living as an American journalist or writer. No one was writing the story of a Vietnamese person as the main character in his own tragedy.

I read VS Naipaul, Joan Didion, Truman Capote and a dozen others who practiced the art of the essay. I began to travel. I reported from Hong Kong, Cambodia and even my homeland, Vietnam. I started to win awards.

The news service grew into something else, however, in the mid 1990s. Instead of looking outward, serving as an alternative source of news about international events, it began to look increasingly inward, to immigrant movements, rising anti-immigrant sentiments, race relations, and the local-global stories of the post-Cold War era.

In 1997, one of my assignments was to ask ethnic media in the Bay Area what they thought of rising anti-immigrant sentiments in California. I didn’t know where to start, so of course I started in the yellow pages, the hulking telephone directories we all had then. I found dozens of media organizations I had never heard of before: there were Chinese and Korean and African American and Spanish language newspapers and radio stations, all within a mile or two of one another. The story turned out to be more than views about anti-immigrant sentiment. Close, then executive editor, decided a convening was needed. So the news service invited about a dozen publishers and editors to a Chinese lunch and from that lunch New California Media was born.

So New California Media began to give out awards to ethnic media journalists; many had been doing great work without any recognition. We organized press conferences. We put together an annual expo in San Francisco, where nearly 100 ethnic media outlets came to showcase their work. It was a time of discovery. Foundations and nonprofit sectors showed up. Politicians showed up. Mainstream media showed up. So did advertisers, though still barely enough of them.

Within a few years, ethnic media outlets outside California heard of the network and wanted to join. So we changed our name once more to include them, and New America Media was born.

Today, advertisers have major ethnic media outlets on their rosters. Many politicians include ethnic media in their press briefings. President Barack Obama in 2013 invited Telemundo for an exclusive interview, a tremendous acknowledgement of ethnic media’s power. And programs like the John S. Knight fellowship at Stanford and the Neiman fellowship at Harvard welcome ethnic media journalists to apply.

Pacific News Service had evolved toward media work and activism and not the exclusive news service that I joined. In truth, I wasn’t happy. I went from being a journalist to doing part-time management of media events. I ran the annual New America Media award for several years, I participated in putting together expos, I worked with nonprofit organizations that wanted to get their messages out to the diverse populations. I consulted with ethnic media. I did journalism on the side.

Yet I stayed. I convinced myself that at least I was free to write about issues that matter to me: immigrants’ rights, refugee stories, racism — that the organization was still a home for eccentrics and free thinkers. If I became a media organizer, it was a small price to pay.

Truth be told, I knew that along with upheavals of journalism world, the news service was dying while New America Media, its creation, was, for a long while at least, thriving: No one was paying to read stories anymore and no one was funding the organization to do journalism. We were slowly turning into a media organizing entity, a non-profit public relations firm, with a news service as a side gig. Perhaps it couldn’t be helped: Pacific News Service was unfocused. it covered everything under the sun, it was interested in every topic. New America Media, on the other hand, had a clearer mission to uplift and inform ethnic media and diverse communities.

But it would have been hard for me to leave. It was home. One writer, Bill Kenkellen, who wrote about religion and gay issues — that’s what we called it back then — told me a about a year after I joined the service, “We are all refugees here.” As a gay man, he had fled his conservative Catholic family. In a sense Pacific News Service was as much a refuge for misfits and homeless kids as it was a place for young, ambitious journalists to find their footing.

Over the years I mentored many. I watched interns turn into bona fide journalists working for major publications. I watched many others have their lives turned around after finding their way through that news service. They found their voices, their articulations. They saw their names in print and something happened to them, as if crossing some mental barrier to enter a public space. The same could be said of those journalists in the ethnic media sectors who won awards: It was an affirmation of what they did, what they continue to do.

Also: A Facebook friend request brought my mom back to Vietnam after 35 years

It is a wondrous thing to look back over the 24 years that I worked at Pacific News Service and New America Media, in term of the human connections that I made and the human dramas that I witnessed. It’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve met more than 1,000 people who walked through our doors.

And I retain myriad stories of tragic endings and marvelous transformations.

What I will always treasure most though is this: The Monday editorial meeting, what I consider the spirit of the place. No ideas too small or too bizarre were turned away. We found the often ignored angles to events, big and small — “Did they provide PSAs in Spanish when the fire started in San Diego?” “Why not include a person of color on that panel on diversity?” “Why not ask an immigrant to tell his own story?” — a form of inclusive journalism that I continue to advocate for in the face of shrinking democracy.

Pacific News Service and New America Media will close their doors on Nov. 30. But in a world awash with intolerance and racism and soundbites, its ideas, its insistence that all sectors need sounding, that we all need to sit together at the table, have spread far and wide.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on The World. Please take our 5-min. survey.