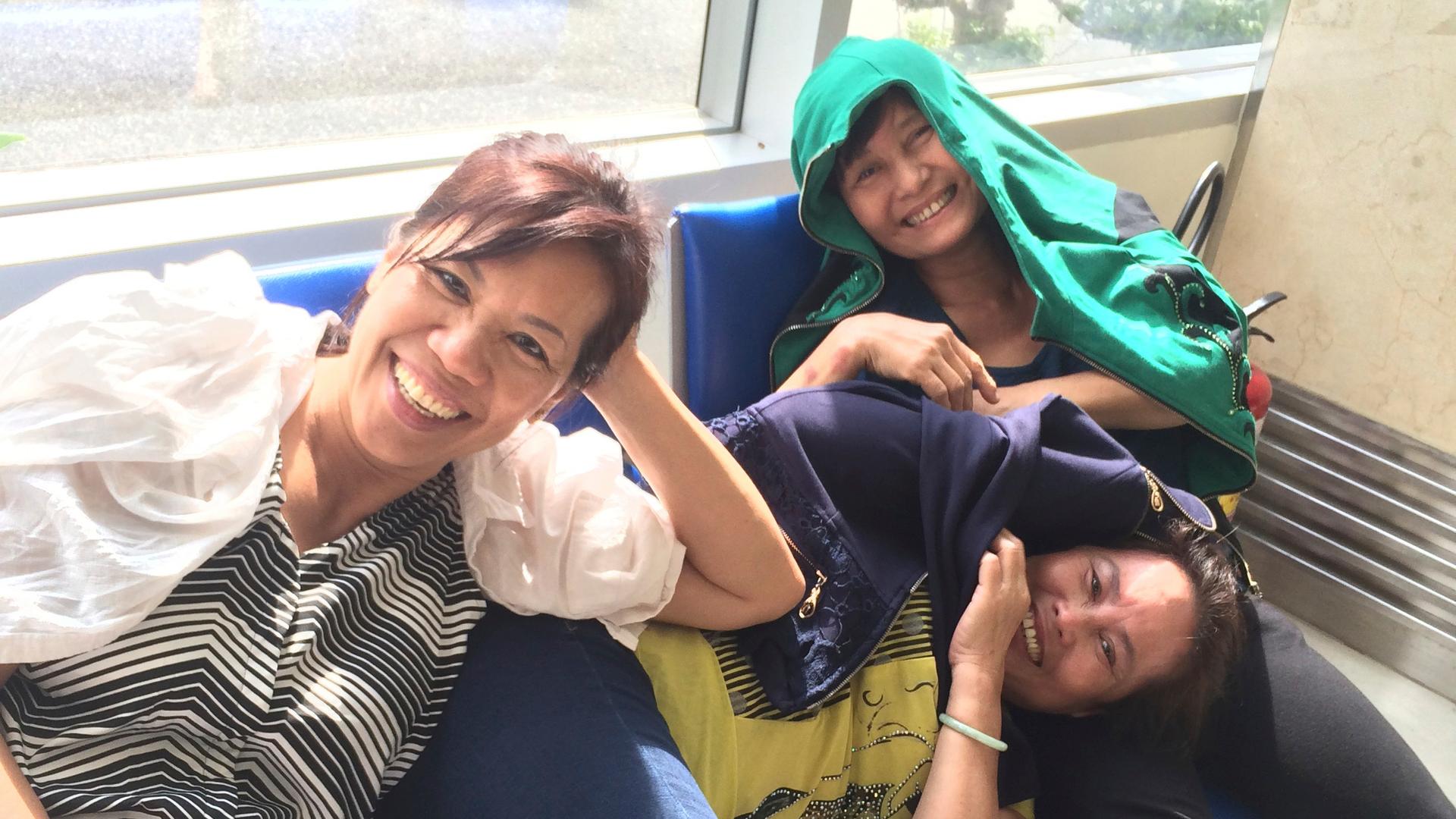

Ngoc Bich Ha, right, reunited with her childhood friends Mai and Tot after 35 years away from Vietnam. She experienced trauma escaping the war, but she found healing in her return. The trio took a short trip to Huế. It was Mai and Tot’s first time on an airplane.

When my mother heard the news that President Barack Obama will land in Hanoi on Sunday, I braced myself for a tirade. I readied myself for a speech about the irreconcilable differences between the US and Communist Vietnam and the futility of such diplomatic gestures.

She’s a Vietnamese refugee, among the older generation of Vietnamese Americans who endured significant trauma fleeing their homeland. She left in 1980 with the second wave of refugees — those who survived the war only to live through half a decade of extreme poverty and political turmoil that followed. These experiences inevitably colored her views in grim terms, which I heard about throughout my childhood.

I was stunned when this time she paused thoughtfully said, “I think it will help us to heal.”

This pivotal shift in her response has everything to do with her own trip to Vietnam last November. It was her first time back since she left 35 years ago and it was a trip that neither of us had ever imagined would happen. She left Vietnam at age 18 under the most horrific circumstances: Her brother and father died from medical conditions exacerbated by war, their village was decimated and she feared retaliation because her brother fought for the southern army. So she got on a small fishing boat headed for Thailand and never looked back.

In 2002, when I was in eighth grade in San Jose, my parents, two sisters and I got US passports with the intention of going back to Vietnam as a family. That month, my mother’s recurring night terrors about escaping and being captured — sometimes by Thai pirates and other times by the Viet Cong — intensified and it became routine for us to wake up to her screaming in her sleep. We eventually just stopped talking about the trip.

What convinced her to get on that plane after three and a half decades? A Facebook friend request.

I should pause here to say that the most consistent pattern in my mother’s social life is her complete lack of one. For as long as I can remember, she’s had little interest in initiating or maintaining friendships, which confounded me because she is the most socially adept and gregarious person I know. She always told me, even as I entered my mid-20s, that friends are a luxury. She spent the first half of her 20s supporting her two sisters and struggling to survive. The latter half she devoted to starting her own family. Eventually, she just got used to the solitude.

So it was a surprise when she told me that she had been searching for her high school best friends for years and that, in the end, they were the ones who found her, through Facebook.

I vaguely recalled stories about a friend named Mai who would give her rides to school on bicycle handlebars during monsoon season. She had also told us about a girl named Tot who once sold her necklace to treat my mom and her younger sister to their first meal at a restaurant. She always retold these stories as if they were from a past life, so it never felt like they were real people and it didn’t occur to me that she still wondered about them.

After her friends first reached out to her, I came home every weekend to find my technophobic mother on a mission to navigate every kind of online calling and video chat app to giggle with these two ladies on the other side of the world. Mai would take the bus five kilometers to Tot’s house and huddle around her tablet to catch up with my mom. On occasion, they would hold ripened mangosteen, creamy durian and custard apple to the camera to remind my mom what home used to taste like.

There was a warm vibrato in my mom’s laughter that I had never heard before. And after a year of Mai and Tot asking if she would come see them, she hesitated, smiled, and said “I’ll do it.”

My mom asked me to accompany her because I had been to Vietnam twice before and could introduce her to a version of her homeland that she had not yet met. She spent three agonizing months committing to the trip and then trying to back out again, even after we purchased plane tickets.

While my mom spent the flight and our first days in Saigon excitedly retelling me everything she knew about these two women I was about to meet, I silently worried. People change — my mom certainly had — what if Mai and Tot weren’t the people my mom had been expecting? Or worse, what if the closeness she had felt reconnecting with these women was purely one-sided?

These thoughts continued to weigh on me from the moment we got on a domestic flight to Rạch Giá, the largest city close to her village on the southern edge of Vietnam, up until the moment our taxi pulled up to the narrow alley to Tot’s house. A woman in a floral pajama set and a wide brim hat made her way toward us. My heart stopped when I saw her expression: stern furrowed brows, her lips set in a hard line. The two women came face-to-face and stared at each other for what felt like an eternity.

My mother broke the spell and threw her arms around Tot in the kind of full-bodied hug that only close girlfriends know how to give each other. As she pulled away, all traces of the hard expression on Tot’s face had been wiped away by damp eyes and a wide grin.

“My friend is really here,” she said in a hushed tone, addressing my mom as much as she was convincing herself of this fact. Tot had moved a few villages away from their hometown, but remained in the Mekong region where she makes her living from rice farming, just as my mother’s family had.

When Mai arrived later, it was nothing short of magic. The three women squatted on the kitchen tiles washing and chopping vegetables for dinner. They transformed into teenagers making inside jokes about the boys they had crushes on in high school. They discussed everyone they had known, Mai shared that the bicycle she drove them to school on was still at her house, and the two ladies agreed that my mom looked even younger and cuter in real life than in her Facebook photos. Between the giggling and frequent selfies, it was as if my mom had just gone a on long trip before coming back home.

I had never seen my mother carry herself with such lightness. The woman I knew battled with anxiety and often lost. Her personality had always been marked by her constant state of worry about imagined predators and worst-case scenarios. I used to feel dread when she began to tell stories about Vietnam, aware that heaviness and pained sadness would often creep into her voice and linger in the room for the rest of the day.

But sitting with these friends grounded her in the best parts of her past. It allowed her to tap into the happiest moments of her young adult life, untainted by bitterness or trauma.

They talked late into each night about what happened after they last saw each other. The men they married, the men they didn’t marry, the major highs and lows, and what survival looked like for each of them after the war. My mother told them about the swing shifts she worked when she first came to America. How she hunched over the microchips she soldered together in an assembly line for hours on end. How this work permanently damaged her neck. Between chuckles, she told them how she had first bought sticks of butter mistaking them for the rectangular ice cream bars back home. She asked questions about neighbors and classmates who left after her and the ones who stayed. Each answer seemed to remove a weight I didn’t know she had been carrying with her all these years.

More: Sonny Lê also came to the US as a refugee from Vietnam. Here's how he found his place — with help from Prince and David Bowie. Plus, the poetry of Ocean Vuong.

But as they laughed full-bellied laughs about the triumphs and tribulations of motherhood, the uphill battle of aging, and their love of food, it struck me that they fit as seamlessly into each other’s present as much as they did in each other’s past.

On their last day together, they shared a solemn breakfast. Each made a brave attempt to crack a small joke to lighten the mood or provide some strength with a subtle squeeze of the hand. They embraced at the airport, made my mom swear that she would come back next year, then rushed away so that my mom wouldn’t see their tears.

It’s been nearly six months since her trip and I am still seeing the impact. She maintains her weekly video chat sessions with her friends and I can hear the full width of her smile through my calls with her, as she delivers updates about Mai and Tot’s latest adventures. She tells me that she sleeps better now and hasn’t had a nightmare about escaping Vietnam since the journey.

So when mom tells me that she feels hopeful about President Obama’s trip, I share in her optimism. She of all people knows that you cannot bridge rifts or find closure in isolation. And even though this will only be the third US presidential visit to Vietnam in 43 years, my mother also knows it’s never too late to heal.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?