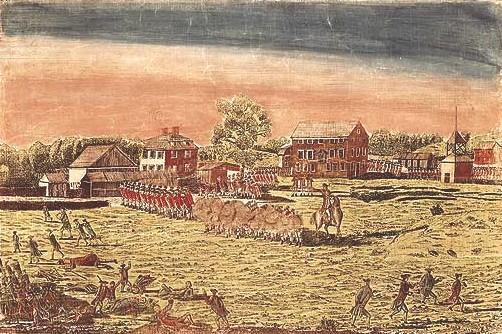

British soldiers are pictured firing on armed colonists on Lexington Green at the start of the American Revolution.

The Second Amendment to the Constitution states simply: "A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed." That language and that idea were clearly important to the Founding Fathers.

But why?

The Second Amendment is rooted in multiple sources: English law; America’s revolutionary experience; and contemporary European political thought. In short, the basic idea was that a people have a right to defend themselves against tyranny; and that if a government breaches the social contract with its people, the people have a right to overthrow that government. Popular access to arms is the sine qua non of such an ideal.

This argument lies at the heart of the Declaration of Independence when the colonists overthrew the rule of the king of Great Britain. So, in a sense, every American celebrates this idea every year.

It’s hard to imagine the generation that launched the American Revolution doing so without embracing the ideas in the Second Amendment.

For the colonists, the fear of tyranny was very real. Absolute monarchy was the norm in mainland Europe. Conformity in religion and politics was enforced by large standing armies. The idea of popular sovereignty was heretical.

Abuses in Europe were well-publicized and made even more real by some of the victims ending up in America as refugees.

One glaring example was the persecution of Protestants in France in the 1680s. Soldiers were billeted in Protestant homes and allowed to steal and abuse the inhabitants until they converted to Catholicism or left the country. Some of these Huguenot refugees found new homes in America.

England and its offshoots in the colonies were an exception to the absolutist trend in Europe, and the Whiggish strand of the political class was constantly on guard against royal encroachments on the rights of the people and their representatives in Parliament.

The Whigs saw themselves as heirs to those who had fought against King Charles I in the 1640s when he tried to restrict parliamentary privileges and were the direct heirs of those who overthrew King James II in 1688.

One of King James’s offenses was to attempt to disarm Protestants. He was seen as pro-Catholic and there were fears he was planning to force conversions.

It was a year after that Glorious Revolution that England adopted its own Bill of Rights. One of the “ancient” rights that it enumerated was the right to keep and bear arms, a fact cited by the US Supreme Court in a key ruling on the Second Amendment in 2008.

The colonists saw themselves as fitting very much into this Whig tradition when they began to resist London’s attempts to start billeting troops in their homes and raising unlawful taxes.

The colonists also drew inspiration from the ideas of political thinkers of Europe’s Enlightenment.” John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in particular, expounded on the “social contract.”

The idea that people can overthrow a tyrannical government may be admirable in theory, perhaps, but the US does not have a good record of accepting the theory when applied against Washington. The US was not happy when the Confederate States tried to put this idea into practice in 1861; nor when the Black Panthers advocated it in the 1960s; nor even when angry farmers in Pennsylvania tried it in the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s.

The core problem, in practice, is who speaks for the people?

Besides the collective right to keep and bear arms, the Second Amendment was probably also designed to defend the individual’s right to bear arms. Some of the earliest legal commentaries in the new republic expound on it, like St. George Tucker’s annotated version of Blackstone’s "Commentaries on the Laws of England."

But the definitive clarification did not emerge from the Supreme Court until 2008, in DC vs. Heller, when the court ruled 5 to 4 that the Second Amendment does refer to the right of individuals to keep and bear arms and not just to a collective right of communities to defend themselves against tyranny.

In a sense, the question before America today is whether the theoretical need to defend against tyranny still outweighs the apparent public health need to reduce gun deaths.