Thomas Sankara declared Burkina Faso ‘the land of people of integrity’

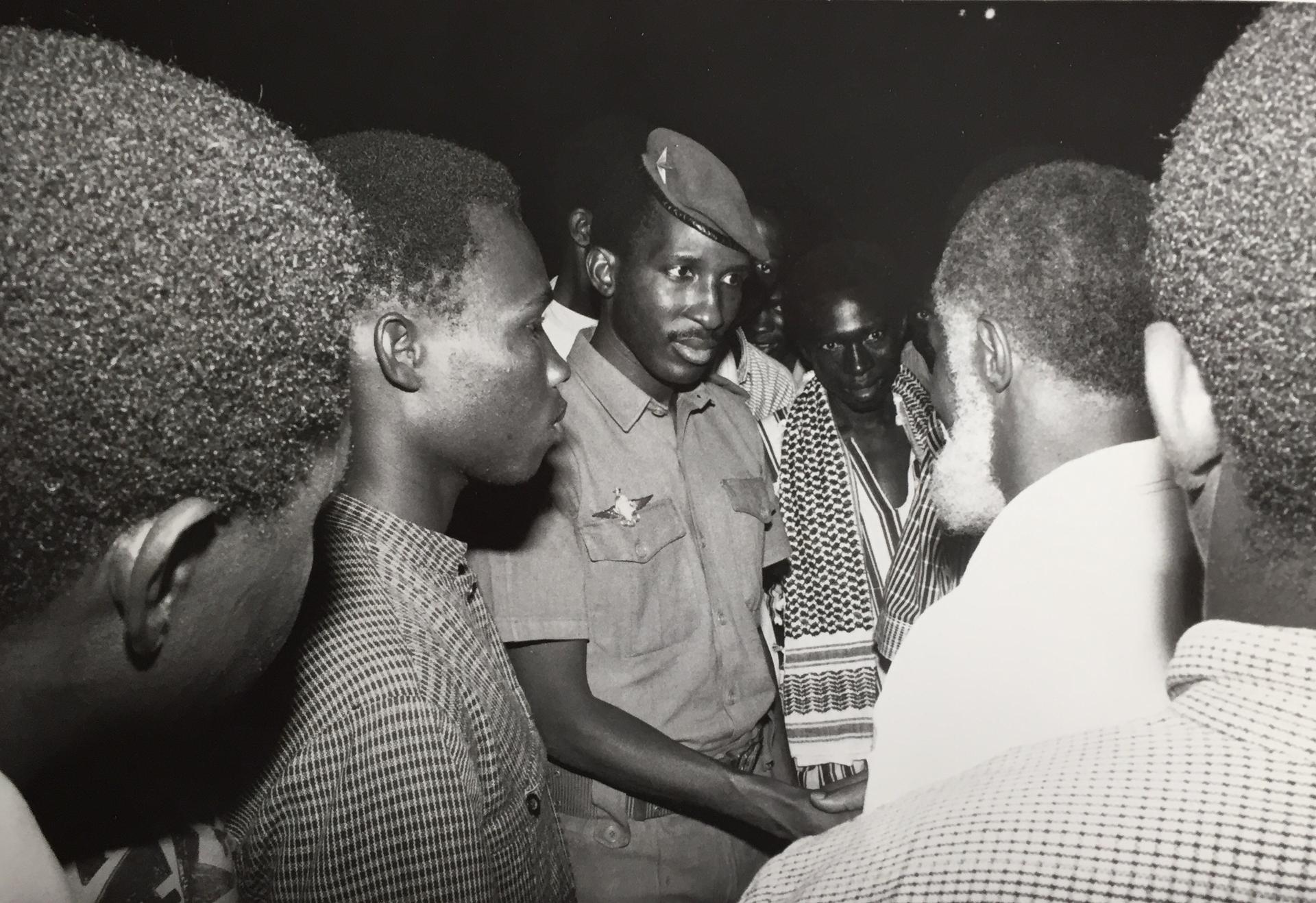

Captain Thomas Sankara

On the first anniversary of the revolution that brought him to power, Captain Thomas Sankara rejected the colonial name of his country — Upper Volta — and by presidential mandate declared the country would be known as Burkina Faso, the land of people of integrity.

It was one of many attention-grabbing things Sankara did. But many of his fellow Burkinabe were OK with that because it was the first time the world paid attention to this impoverished, landlocked country.

According to Sennen Andriamirado, the late Malagasy journalist who chronicled Sankara’s rise and fall for the magazine Jeune Afrique, Frenchman Albert Londres arrived in Upper Volta in 1930 and described it like this: “We arrived in the land of the Mossi people. It’s known in Africa under the name ‘human labor pool’: Three million negroes. Everyone draws them like water from a well.”

In more recent decades, the Mossi and Bambara people have been economic refugees who went south to find work in the cocoa and coffee plantations that power the economies of the Ivory Coast and Ghana. Today, there are millions of Burkinabe and their descendants in the littoral countries along the Gulf of Guinea.

But the reputation that Upper Volta got stuck with was “backwards and isolated.” As Andriamirado explains in “Sankara le rebelle,” which came out in 1987, “on the eve of independence [in 1960] and the twenty years since, landlocked Upper Volta has remained the hinterland of West Africa.”

So when Sankara stood at the podium of the UN on October 4, 1984 as president of “the land of people of integrity,” there was some heavy lore that his people — and many others — understood in his uncluttered opening words: “I am here to bring you fraternal greetings from a country that covers 274,000 square kilometers, and whose 7 million children, women and men refuse henceforth to die from ignorance, hunger and thirst. These are people who, despite a quarter century of existence as a sovereign state represented here at the UN, are still not able to really live.”

Sankara continued getting attention for one-year-old Burkina Faso by making a splash in New York City during that visit in October 1984. In Harlem, he opened an exhibit of Burkinabé art (the name of the country was so new, people barely knew what the adjectival form was); at a rally for black nationalism at the Harriet Tubman School, also in Harlem, he thrust his army-issued revolver in the air and told the crowd of 500 cheering people that he was ready to fight imperialism; and then he spoke at the UN.

Making a virtue out of his country’s poverty got to be an act that wore on the elites who were in Sankara’s retinue, who began to feel that being at the top ought to at least have a few privileges. Other countries in the region saw Sankara biting the hand that fed him crumbs.

But his attempt to play a trick on Muammar Gadhafi — though not Sankara's finest moment — would be remembered fondly by every head of state in Africa who ever had to kowtow to Gadhafi in exchange for the millions he gifted to them over the years

In 1986, on a return trip from Moscow with a Burkinabe delegation of 50 people, Sankara was loaned a Soviet jet. He instructed the crew to make a stop in Tripoli where, displaying enormous chutzpah, he asked Gadhafi to borrow a Boeing 727 for the final leg to Ouagadougou. Gadhafi accepted, assuming the Soviets would turn around and go back to Moscow. Instead, two planes landed in the capital of Burkina Faso, each three-quarters empty. The Soviets returned to Moscow the next day, but Sankara grounded the Libyans in Ouagadougou, and put them up at the city’s only four-star hotel.

Frantic appeals from Gadhafi to get his plane back received radio silence as Sankara and his aides tried to find someone, anyone, in Burkina Faso who knew how to pilot a 727. Not even the local crews for Air Afrique had the skill. So ultimately Sankara let the Libyans return to Tripoli, with relations seriously frayed between the two leaders.

Even though Sankara’s plan to kidnap one of Gadhafi’s planes failed, it became the thing of legend, emblematic of one president’s efforts to let the world know that his country was poor, but that he and his people would not be pushed around.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!