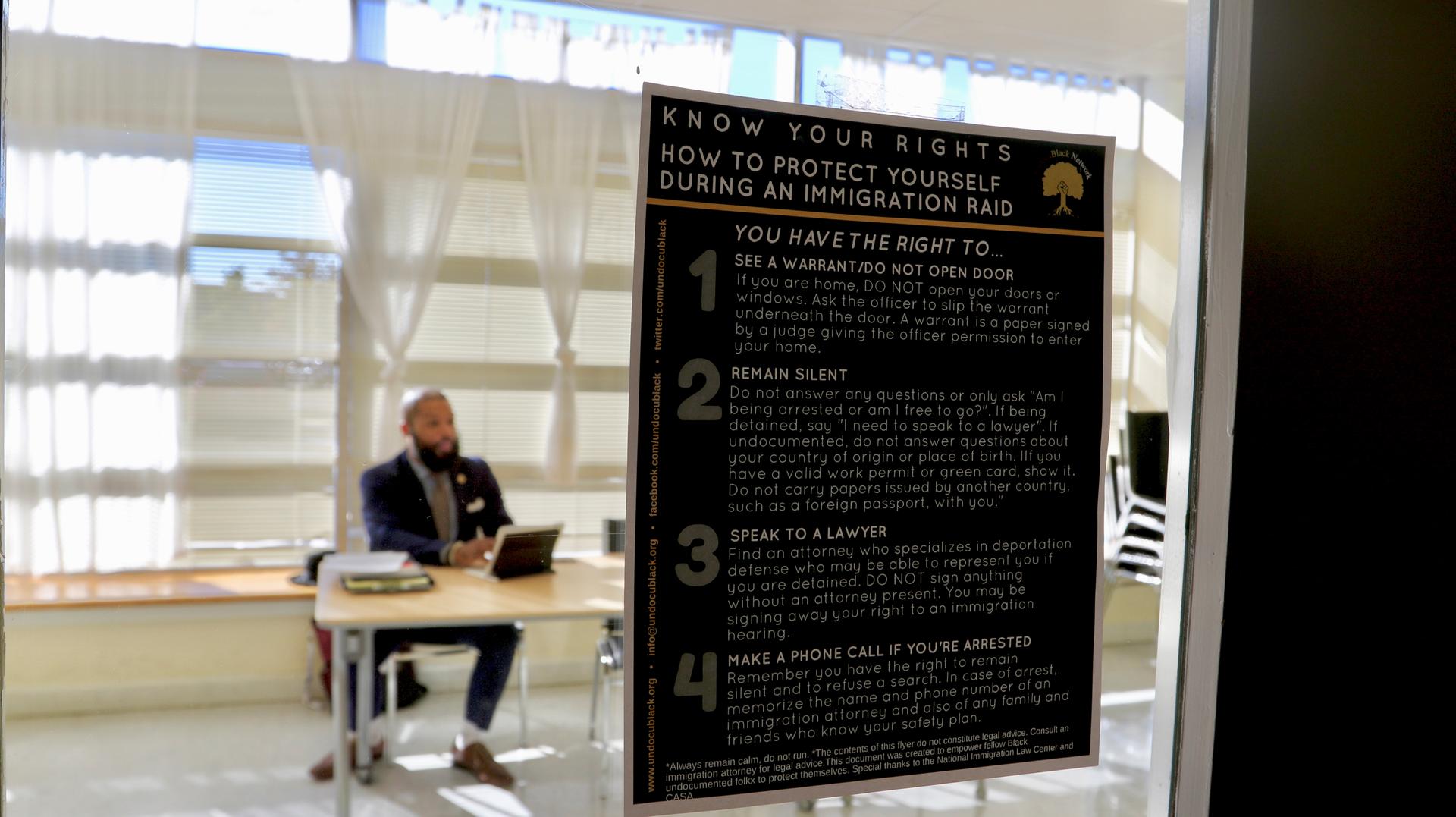

A volunteer with UndocuBlack Network combs through paperwork during individualized, private clinics with would-be DACA renewal applicants on Oct. 3, 2017, in Washington, DC. Not everyone who comes is eligible and a team of immigration lawyers and volunteers offer counsel for those who aren’t.

Thursday is the deadline for more than 150,000 undocumented immigrants in the US enrolled in Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, to renew their status before the program officially ends. DACA allows undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children temporary protection from deportation and access to work permits.

Over the past four weeks, tens of thousands of DACA recipients have rushed to renew their status for two-year extensions before the Trump administration’s Oct. 5 deadline.

In Chicago, a community organization in the Pilsen neighborhood called The Resurrection Project has submitted at least 20 DACA renewal applications weekly on behalf of its clients — up from just a handful in a typical week — plus up to 60 more at each of several walk-in legal clinics it has held at community centers, churches and schools.

The mood is often sadness and disappointment, said Laura Mendoza, an immigrant organizer for the group who is a DACA beneficiary herself.

“Today, we had a client who came in for a consultation and just started crying,” Mendoza said Wednesday afternoon. “She thought she didn’t qualify for renewal but she actually was a candidate. But with the stress, people just don’t have all the information they need.”

The group was surprised that more DACA recipients did not come in for assistance. About 154,000 people nationwide were eligible for renewal during the one-month window, and legal-aid providers scrambled to supply free lawyers and fee assistance for the applicants.

As of Thursday morning, US Citizenship and Immigration Services had received only 60,000 renewal requests, according to spokesperson Katie Tichacek. Another 58,000 people, including Mendoza, renewed before the Trump administration announced it would end the program. That means about 36,000 eligible DACA recipients were unable or chose not to apply for renewal.

Mendoza said the tight deadline, lack of access to legal help and inability to pay the $495 renewal fee on short notice contributed to eligible DACA recipients not applying.

“And people are afraid because they don’t trust the government anymore, so they didn’t want to give their information by renewing,” Mendoza explained. “Fear definitely has a huge role in it.”

Advocates says the timing has been too tight for many DACA recipients, particularly in Texas and Florida, two states with high concentrations of undocumented immigrants that are recovering from record-breaking hurricanes. They worry the stress and cost of rebuilding could cause people to miss the renewal deadline.

“We have a lot of people who just went through such a big disaster,” said Oscar Hernandez, a DACA recipient and an organizer for United We Dream in Houston. “And even if they could have afforded the $495 and the attorney fees, now it’s an added expense, given that a lot of families lost everything.”

In September, advocates and lawyers called the deadline arbitrary and asked the federal government to create an extension.

Related: Why this DACA recipient won't be extending her protected status, but says others should

What’s at stake for many are academic futures and career prospects, in addition to fear that DACA recipients or their families will become more vulnerable to detention and deportation.

The Migration Policy Institute estimates that 241,000 of about 1.2 million people who were eligible to apply for DACA are students enrolled in college. But the DACA program has also spurred states to make higher education more accessible for undocumented immigrants, in general. Since DACA began in 2012, many state governments and individual schools have adjusted admissions standards and financial aid qualifications to accommodate undocumented students who, before, could not enroll or afford college. The Brookings Institute reports that 21 states, for example, offer in-state tuition to undocumented students who would otherwise have to apply and pay for college as foreign or out-of-state students.

Mwewa, who asked that we not use her last name because of her immigration status, came to the US as a child from Zambia 17 years ago, at age 4. But because she was undocumented, she was not considered a resident of Maryland where she has lived all that time. She applied to 13 universities in 2010 but was rejected from 11 schools though she met basic qualifications.

“I wasn’t applying to schools that I shouldn’t have gotten into but I think the only reason I was being denied was because I was being treated like an international student,” she says.

In 2011, the state passed the Maryland Dream Act, which offers limited in-state tuition for undocumented students regardless of their DACA status. But it is a state law designed for students who begin at community colleges, so Mwewa did not qualify.

But she got DACA status in November 2012, so she became eligible for in-state tuition. She enrolled at the University of Maryland in 2014 and paid $10,000 per year instead of the $32,000 the university charges out-of-state students.

Mwewa is also the Washington, DC, regional lead for UndocuBlack Network that serves black, undocumented immigrants nationwide. She organized pop-up clinics this week to help last-minute renewal applicants, though she cannot renew herself. Her DACA status will expire in August 2018, and she’s not sure yet what she’ll do. She hopes to finish her undergraduate degree soon, but without new laws from Congress or new executive actions, she will not be able to apply for a work permit.

“Once their DACA status is no more, they’re no longer eligible to work here,” says James Billings-Kang, a commercial litigation attorney who volunteered to help last-minute DACA applicants. “Many of these people have families, spouses. Will they have to tell their employer they’re no longer eligible to work here?”

The last-ditch effort to close the 36,000-person gap of DACA renewals will soon come to an end. But even after Thursday, there are still several steps before those who applied will be approved. It’s not guaranteed that those who submit applications will have their status extended. Billings-Kang likened the entire application process to at-will employment policies.

“The decisions are all discretionary. The individuals who are considering your DACA renewals can deny your application for any reason, or no reason at all,” he says. “Needless to say, unfortunately, you’re not in the clear. Just because you apply for renewal, that won’t mean you get approved.”

Related: High school is hard enough without having to deal with the loss of DACA