Harry S. Truman’s grandson speaks out against nuclear weapons

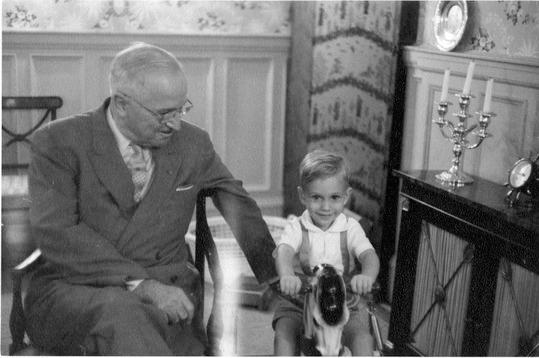

Clifton Truman Daniel with his grandpa, former President Harry S. Truman, c.1963

Harry S. Truman was perhaps one of the most influential presidents of the 20th century. He oversaw the end of World War I and rose to the challenge of the Cold War. He was crucial to the creation of international organizations like the United Nations and NATO.

But for many people, Truman is remembered for one thing: his decision to drop nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, in August 1945.

His eldest grandson, Clifton Truman Daniel, is now an advocate against nuclear weapons.

He says his grandfather was consistent when it came to explaining the decision to use the bomb. “He made the decision [in order] to shorten the war, and save American lives, primarily, as well as Japanese lives had the war gone on, had there been a full-scale invasion.”

“The scholarship on that goes back and forth,” cautions Daniel. “But grandpa, having made the decision, nonetheless felt horrible about the destruction, about the loss of life.”

Daniel recounts the story of a US military photographer, Joe O’Donnell, who documented the aftermath of the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. O’Donnell had an opportunity to meet Truman alone in 1950. According to Daniel, “O’Donnell just took a chance and asked my grandfather, 'Did you ever have any regrets using those weapons?' and my grandfather said 'Hell yes.’ He didn’t want to have to do that.”

Truman never spoke with Daniel about the atomic bombings. “I learned about them like everybody else, in history class and from my books. And the books didn’t tell me much — you get casualty figures but it doesn’t really tell you what happened on the ground.”

Daniel's big insight into the horrors of nuclear war didn’t come until he was in his 40s, when his son was 10. “He was in school here in Chicago, in fifth grade,” says Daniel, “and he came home with a book called 'Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes.' A fictionalized account of a true story.”

The true story belonged to Sadako Sasaki, who developed leukemia ten years after being exposed to radiation at Hiroshima. "In an effort to save her own life, she followed a Japanese tradition that says if you fold 1,000 origami paper cranes, you are granted a wish, or long life or health," Daniel says.

Sadako folded 1,300 cranes, but unfortunately it did not save her life.

“That was the first human story I had ever seen of Hiroshima or Nagasaki,” says Daniel. A Japanese reporter picked up on the fact that Daniel had read it, and out of blue he got a call from Sadako Sasaki’s brother, Masahiro, himself a survivor.

They finally met, in New York, at the 9/11 Tribute Center. “Masahiro and his son Yuji were donating one of Sadako’s original cranes as a gesture of healing,” explains Daniel.

“At the end of our meeting, Yuji Sasaki took out a small plastic box and dropped a tiny paper crane into my palm and said, 'That’s the last one Sadako folded before she died. Would you come to the ceremonies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki?’ And I said yes.”

Daniel took his family and met with more than two dozen survivors.

“It’s hard to explain. It’s hard to describe,” Daniel says when asked to explain how that felt, particularly as the grandson of the man who ordered the attacks.

“It’s heart-wrenching. It’s hard. It’s horrible to hear these stories,” he says. “But as hard as it is for the listener, it’s harder still for the survivor who relives that day over and over and over again, solely in an effort to let the listener know what it was like, so that we don’t do it again.”

Daniel says he did not feel any residual guilt, but he did feel responsibility. “Not responsibility for the bombings, but responsibility to do what I could to help ensure that it doesn’t happen again.”

“All [that] the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki asked me, were to please help them tell their stories,” says Daniel. “So I’ve tried to do that.”