As drought conditions worsen, famine looms over Kenya

A student waits to collect her ration of emergency food relief in Baringo County, Kenya. Kenya is one of several East African countries experiencing a severe drought, which has led to widespread food insecurity throughout the region.

In Baringo, Kenya, the schools are quiet. The sounds of busy classrooms, English lessons and children’s laughter are gone. Instead, they've been replaced by nearly empty classrooms and a handful of children who are just too hungry to learn.

After months of slow starvation, the students have stopped complaining, said Reuben M. Chelbon, a teacher at Lelen Primary School.

“They just say ‘my head hurts’ or ‘I’m too tired.’ To us, that is a sign that the child is hungry,” he said.

Around 31 million people in the Horn of Africa region are experiencing food insecurity or famine, according to the Food Security and Nutrition Working Group. And across the region, millions more are at risk.

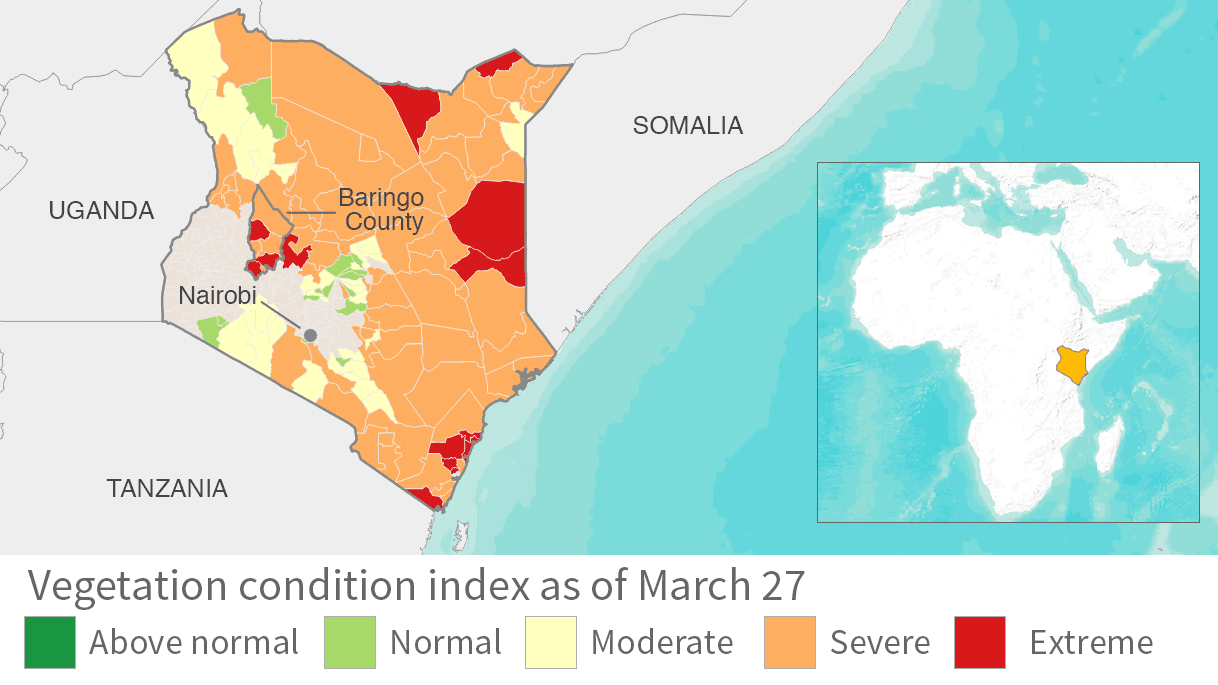

In Kenya’s Rift Valley, known as the breadbasket of the country, almost one-third of the population is suffering from acute malnutrition; an ongoing drought and recent infighting ahead of August’s presidential elections are only worsening an already dire situation.

Facing failing crops, barren livestock and a twofold increase in food prices, many say this is the most severe drought here in a decade.

“This is one of the worst,” said Michael Wafula, country director at Childcare Worldwide. “The drought is killing animals in the thousands, and when thousands of animals die, what does that mean? That means it’s their only source of livelihood. They have nothing else,” he said.

Wafula and his team recently reinstated their emergency food relief program after several seasons of low rainfall and deteriorating harvests. Now, they are providing basic foodstuffs to hundreds of families across central Kenya. They dole out rations several times a week, visiting multiple distribution sites in a single day.

“Last week, we gave to 300 families and still it’s not enough,” said Samuel Mwaura with Childcare Worldwide.

“We wish we could feed everyone but we cannot. We can only feed a few,” Wafula added.

A worsening problem

Drive around Baringo County, population of more than 700,000 people, and you’ll see the signs of encroaching famine. Cows are thin at their haunches, sheep stubbornly graze barren soil and goats attempt, in vain, to pull leaves off wild thorn bushes. The only signs of water are the small pools of muddy water from a brief shower the night before. Too dirty, even the animals won’t drink it.

But what you won’t see are images synonymous with full-blown famines in East Africa, such as children with swollen bellies and sunken eyes, infants stalked by vultures or thousands of refugees lining up en masse to receive their food rations.

That lack of public suffering in Kenya’s Rift Valley doesn’t mean the situation isn’t serious, though. Up to 30 percent of Baringo’s population is experiencing acute malnutrition, and 3 million across the country are facing acute food insecurity with the number expected to increase in the coming weeks.

But with the declaration of official famine in Somalia and South Sudan, the developing — and probably avoidable — catastrophe in Kenya just can’t compete with the crises in surrounding countries. Perhaps it’s that circumstantial apathy that makes Kenya’s drought so insidious; without media coverage or targeted intervention, the slow, needless starvation of millions of Kenyans continues to unfold.

Related: Drought doesn't cause famine. People do.

Handing out food

On March 27, a crowd gathered as staff from Childcare Worldwide arrived at the African Inland Church in Mugurin to distribute food. What began as a line of several dozen people quickly ballooned into hundreds. Most were farmers or cattle herders — all in need of food to supplement several poor harvests and dead livestock.

A small, well-organized group of staffers from Childcare Worldwide handed out rations of maize, beans and cooking oil to every family registered in their feeding program. Most of the beneficiaries were women with young children or elderly people, as the men had taken their cattle miles away in hopes of finding greener grazing areas.

For many who arrived on foot, it was a struggle to carry the bulky bags of food rations and jugs of cooking oil all the way home.

Lately, many of them have also been walking three times farther than usual, in search of water.

Primary schoolteacher Alice Kipkeno said the drought has stemmed, in part, from low rains over the past several years.

“Last year, it was a small harvest and for so many people, there was no harvest,” she said.

But despite early predictions of this drought, the government has only provided two water tanks in the community and delivered maize rations twice, she said. “But the population is larger, larger than that contribution.”

Wafula underscored that point, stating that while the government might promise drought relief assistance in Baringo, getting those resources to the people who need it is a complex and oftentimes corrupt process.

It's unclear where, exactly, it ends up. “One of the issues that we have faced over time is the issue of impunity,” he said. “Maybe a politician was given food … but when you go to the ground, you don’t see that food.”

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Then there's the lack of water access. In the last year, Childcare Worldwide has provided 132 rainwater-harvesting tanks to collect water in communities suffering from drought, Wafula said.

“Maybe the government has good intentions, but we ensure that this gets to the ground where the need is,” he said.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

A shortage of water and food

The Childcare Worldwide staffers arrived at Lelen Primary School, midday, during its March 27 distribution and began unloading bags of food and cooking oil from their minibus. A group of students slowly ambled across the dried-up school grounds toward the visitors; most were shoeless, the soles of their feet burning under the scorching Kenyan sun.

Fewer than a dozen students, most aged 7 to 13, were in attendance at Lelen that day. Normally, it's closer to 100. Likewise, thousands of students all over Kenya have stopped coming to school altogether, as a result of the drought conditions.

“These children only eat one meal a day,” said Chelbon. “And even the wells have dried.”

There are 1,980 families in Baringo County who don’t have enough to eat, said Wafula.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Then there are those who can't make it to the distribution sites. Like 90-year-old Cherutich Kigen, who could be found a half-hour drive's away. Blind and partially deaf, Kigen sat under the shadows cast by his small, single-room tin house, which was built by a nonprofit several years before.

Dependent on handouts, Kigen said he has no food or water aside from what he’s been given by local nonprofits.

“Since the famine, the young have gone and I has been left alone,” he explained, turning his eyes toward the sky. “There is nowhere to get food.”

No end in sight

At a clinic on the outskirts of Baringo, nurse Phoenix Kipkoiyo waited for patients to arrive. She typically treats 30 patients a day, mostly for respiratory infection but sometimes for malnutrition. The number of underweight children is increasing as the drought drags on, she said.

“There is a shortage of water and even food. Because of that climate change, there is not enough. The staple food [is] not enough, and there is no nutritious food,” she added.

That is backed up by numbers, too: 3 million people are in need of food assistance in Kenya, more than double the figure dating back to August 2016, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

This past February, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta declared the drought a national disaster, committing $99 million to the government's response. However, Kenya needs more than another $109 million to curb the drought, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Unfortunately, without greater intervention, researchers say, it appears that the situation will keep deteriorating.